Orit Gat

Orit Gat

Embodiment, ephemera, and radical causes: works from 1970 to 1990 by over one hundred UK women artists, on display at Tate Britain.

Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, installation view. Courtesy Tate Britain. Photo: Madeleine Buddo. © Tate.

Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, curated by Linsey Young with Zuzana Flaskova, Hannah Marsh, and Inga Fraser, moving image works cocurated with Lucy Reynolds, Tate Britain, Millbank, London, through April 7, 2024

• • •

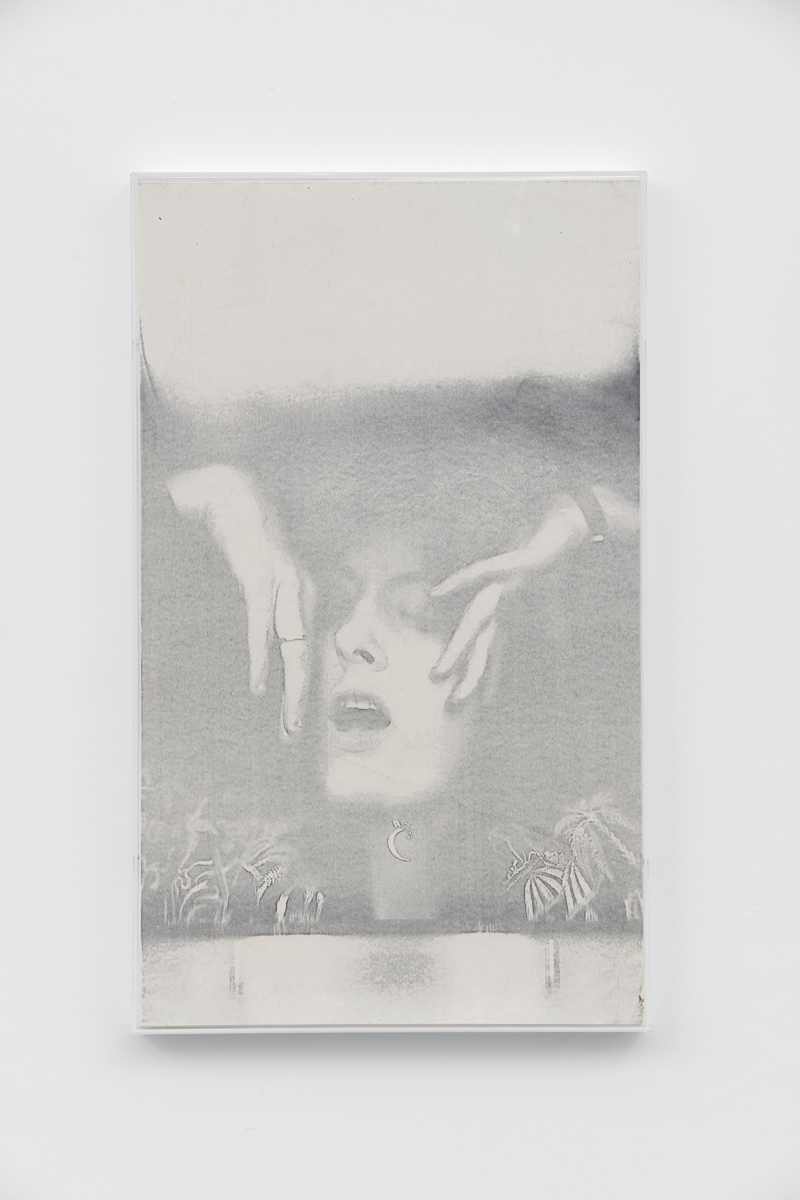

Penny Slinger’s Spirit Impressions 2–5 (1974) now occupy the same museum, Tate Britain, as John Everett Millais’s Ophelia (1851–52). Slinger made these four Xerox monoprints by resting her face and hands on a photocopier, creating black-and-white impressions in which she seems underwater, so reminiscent of the famous Pre-Raphaelite painting that shows Ophelia drowned in a river. This visual twinning was occasioned by Women In Revolt!, an exhibition featuring more than one hundred women artists whose works conjure a history of the representation of women, with a focus on—and refusal of—the subjugating image culture of the 1970s to the 1990s.

Penny Slinger, Spirit Impressions – 2, 1974. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery and Blum & Poe. © Penny Slinger / Artist Rights Society.

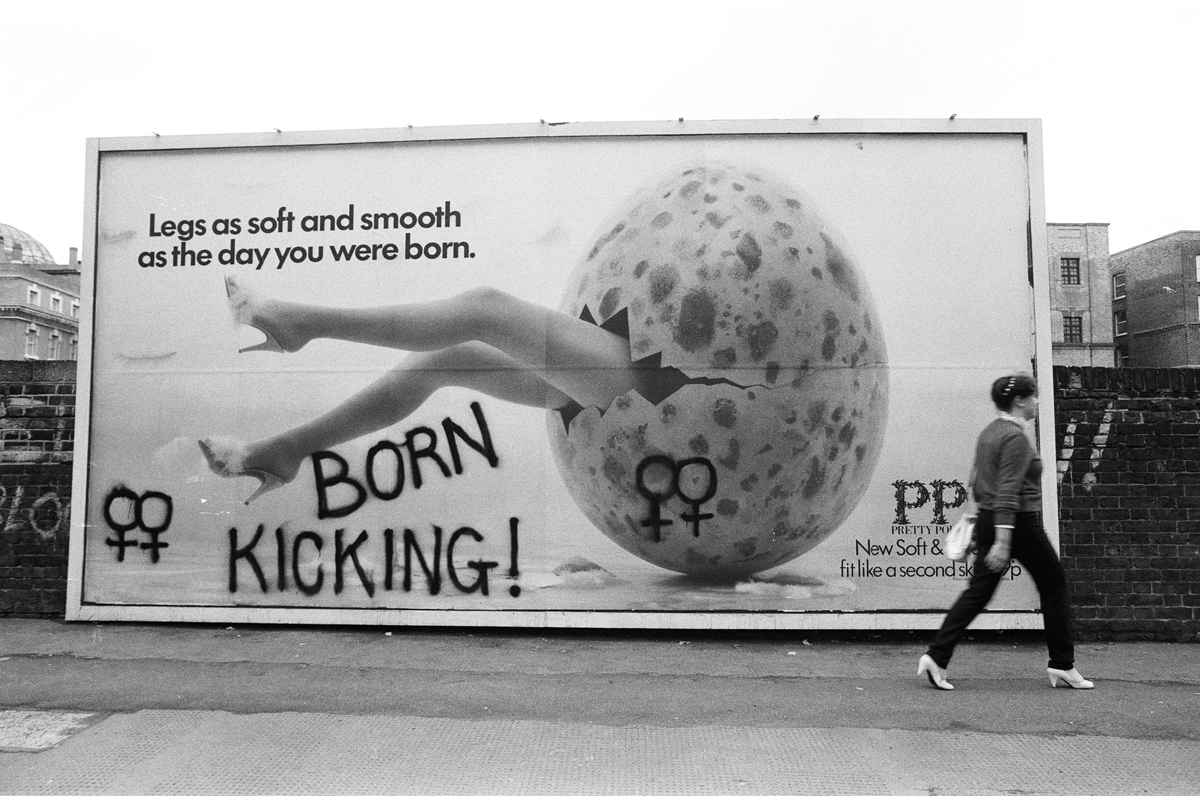

The repudiation is seen, for example, in Jill Posener’s beautiful punk gesture, where she and collaborators from a lesbian squat she lived in spray-painted over misogynist ads in London streets. On a campaign showing a pair of high-heeled legs breaking out of an egg, the copy reading “Legs as soft and smooth as the day you were born,” they scrawled “BORN KICKING!” (1983). They photographed these actions and sold the prints as postcards to raise money for radical causes. Six framed photographs of these marvelously angry public interventions are included here; the postcards are not, though they would have been at home in this exhibition, which displays hundreds of pieces of ephemera and archival items, such as photos, postcards, posters, zines, and little button badges that read things like “YBA WIFE” and “Don’t do it, Di.”

Jill Posener, Born Kicking, London, 1983, reprinted 2023. Courtesy the artist.

All this rigorously assembled material, most of which is presented in vitrines and glass cases, contributes to a visual tension in the show, which tries hard to balance archival and documentary objects with the living presence of the women who are its subject—to ensure they are not just depicted in black-and-white photographs and films but are also included in the space in an embodied way. This physicality is offered by works such as Janis Jefferies’s Double Labia (1980), a rug-like woven construction dyed hot-red that hangs from one wall. The sound from Gina Birch’s Super 8 short film 3 Minute Scream (1977) chillingly fills the next room, which is also occupied by Rita McGurn’s untitled human-size crochet figures arranged on a circular podium, like a group of women hanging out in a living room. Margaret Harrison’s installation Greenham Common (Common reflections) (1989–2013) recreates a part of the perimeter fence from Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp outside the Berkshire military base, occupied by a movement advocating for peace and nuclear disarmament for almost twenty years between 1981 and 2000, when the base closed and a commemorative memorial to the women’s efforts was built on the site. The display of the fence—with objects like mirrors, children’s clothes, and kitchen items embedded in the wire—suggests a lived presence: this is not an image of revolt, but a remnant and reminder thereof.

Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, installation view. Courtesy Tate Britain. Photo: Larina Fernandes. © Tate. Pictured: Margaret Harrison, Greenham Common (Common reflections), 1989–2013.

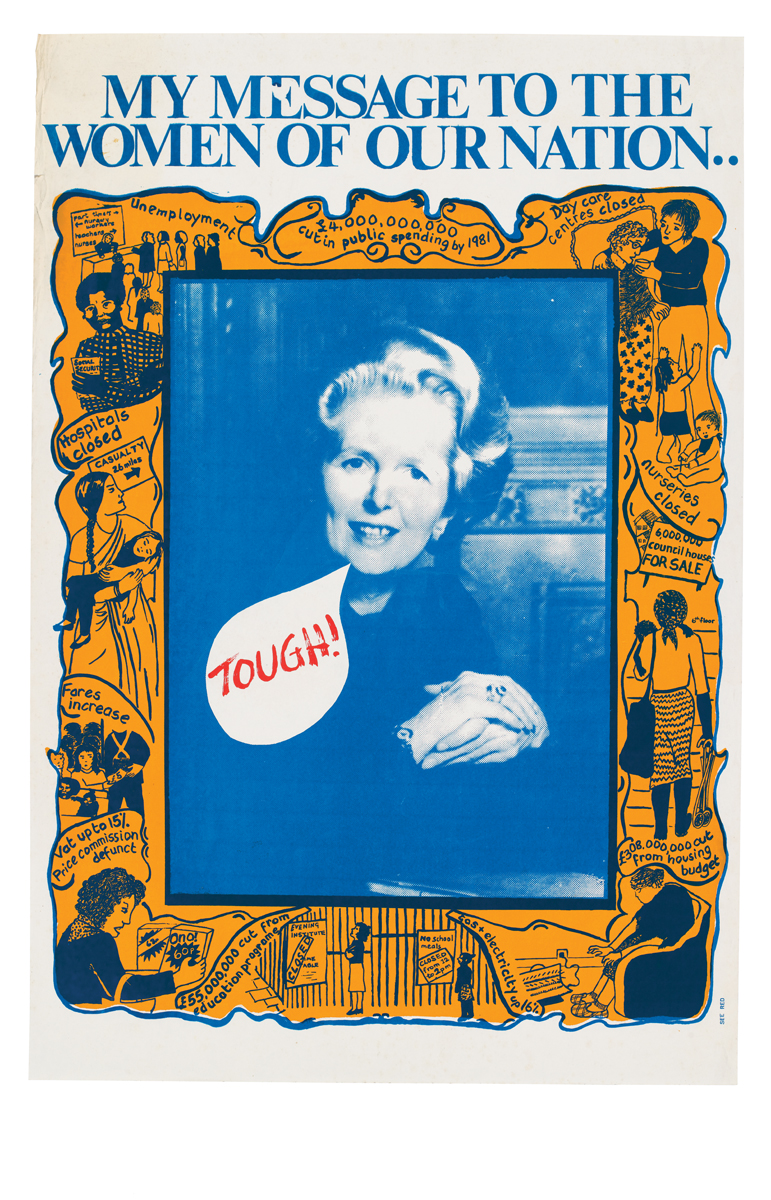

The period the exhibition covers is not a distant past. There isn’t much curatorial explanation of the focus on the two decades in question, though that era’s politics, especially the eleven years of Margaret Thatcher’s rule, define the UK to this day. The See Red Women’s Workshop poster Tough! (1979) has a speech bubble with that word coming out of the mouth of then-newly elected Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, surrounded by a frame detailing how Thatcher’s policies, from cutting millions in public spending to closing day-care centers, harmed women. It’s an official poster the collective repurposed: they wrote to Thatcher’s office asking for a portrait, and one was unsuspectingly sent to them; Thatcher’s staffers must have thought a feminist group wanted to commend the first female Prime Minister, who was famous for sayings like “there’s no such thing as society” (in an interview for glossy magazine Woman’s Own in 1987) and “there is no alternative”—to capitalism, that is. Seen today, in a country that has lived under a conservative government’s austerity measures for over a decade, it’s a great reminder of the Thatcher fallacy: the idea that a female head of state would be good for women (or for that nonexistent thing, society) by virtue of being a woman.

See Red Women’s Workshop, Tough! My Message to the Women of Our Nation…, 1979. © See Red Women’s Workshop.

Direct responses to the politics of the period appear throughout. The 1980s sections are dedicated to events in the UK from Princess Diana’s 1981 marriage to Prince Charles (don’t do it, Di!—the royal wedding and its celebration of power and family norms was a slap in the face for the many women working for gender equality and liberation) to the miners’ strike in 1984–85. A big banner by Thalia Campbell (Thatcher’s Thugs, 1984) shows a riot police officer in Orgreave, the coal mine forever associated with Thatcher’s forceful suppression of the strike. Poignantly, in the next room—dedicated to the feminist members of the British Black Art Movement, founded in the early ’80s—is another representation of police violence. Marlene Smith’s Good Housekeeping III (1985/2023) is a portrait of Dorothy Cherry Groce, shot at home by police officers in Brixton in 1985 during a raid searching for her son. Made of chipboard, plaster, and cloth, it shows Groce next to an old family photo. Written on the wall is the sentence, “My mother opens the door at 7am. She is not bulletproof.”

Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, installation view. Courtesy Tate Britain. Photo: Larina Fernandes. © Tate. Pictured, right: Thalia Campbell, Thatcher’s Thugs, 1984.

In contemporary politics, feminism (especially with the addition of the qualifier “white” before it) is often discussed like a bad thing, out of touch with the political reality, an insufficient subject position. And yet, many of the concerns of the women’s movement reflected in this exhibition still resonate: cuts to social programming. Lack of affordable housing. A health care crisis that affects women specifically and women of color disproportionally.

Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, installation view. Courtesy Tate Britain. Photo: Larina Fernandes. © Tate. Pictured: Marlene Smith, Good Housekeeping III, 1985/2023.

I don’t recount this to insinuate that nothing ever changes. I do so to appreciate how, as the fight continues, Women In Revolt! repopulates my world with a multiplicity of images of women—and women’s struggle—that have been erased or sidelined: many of these works have not been shown since the 1970s, and many of the materials lists include the telling phrase “reprinted 2023” by photos that have been out of circulation for decades. Still, my main takeaway is that the real power—or the revolt—is in a coming together. The collectivity, the friendship, the abundance and multiplicity of beliefs and strategies for collaboration, the joy. All these images of women, working toward a common goal. With their heads above water.

Orit Gat is an art critic and writer living in London whose work on contemporary art and digital culture has appeared in a variety of magazines. She is working on her first book, If Anything Happens, an essay on football, love, and loss.