Kareem Estefan

Kareem Estefan

In his first Beirut solo show, the artist explores walls, sound,

and reincarnation.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Earwitness Inventory, 2018–ongoing (installation view). Installation including 95 items, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan: Natq, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut, Lebanon, through January 4, 2020

• • •

Natq, the title of Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s largest exhibition to date (and first solo exhibition in Beirut, where he has lived for several years), might be translated as pronunciation, vocalization, the physical act of speaking, or, according to the press release, speaking the truth. It’s not surprising this latter, less-common meaning would be significant for the British-Lebanese artist. He is perhaps best known for his work with Forensic Architecture, with whom he has conducted high-profile audio investigations into restrictive asylum policies in Europe and state violence in Syria and Palestine/Israel. (The research agency is led by Eyal Weizman at Goldsmiths, University of London, where Abu Hamdan received a PhD in 2017.) His sonic analysis of Syria’s Saydnaya prison, created in collaboration with “ear witness” survivors (who were forcibly prevented from seeing their surroundings while imprisoned), enabled Forensic Architecture to reconstruct the hidden site’s spatial contours and key incidents of abuse for an Amnesty International report that concluded the prison administered mass torture and execution.

A finalist for this year’s Turner Prize, Abu Hamdan shares Forensic Architecture’s keen attunement to material traces of violence and employs similar techniques of data analysis and visualization. But his own practice—whether audio documentaries, video installations, lecture-performances, or photographic prints—is marked by a greater emphasis on the poetics of evidence. This is true even when the artist draws on research conducted with Forensic Architecture for solo works, as he does throughout Natq with Saydnaya-related material; he transmutes legal inquiries into more open-ended explorations of the politics of sound and the aesthetics of information.

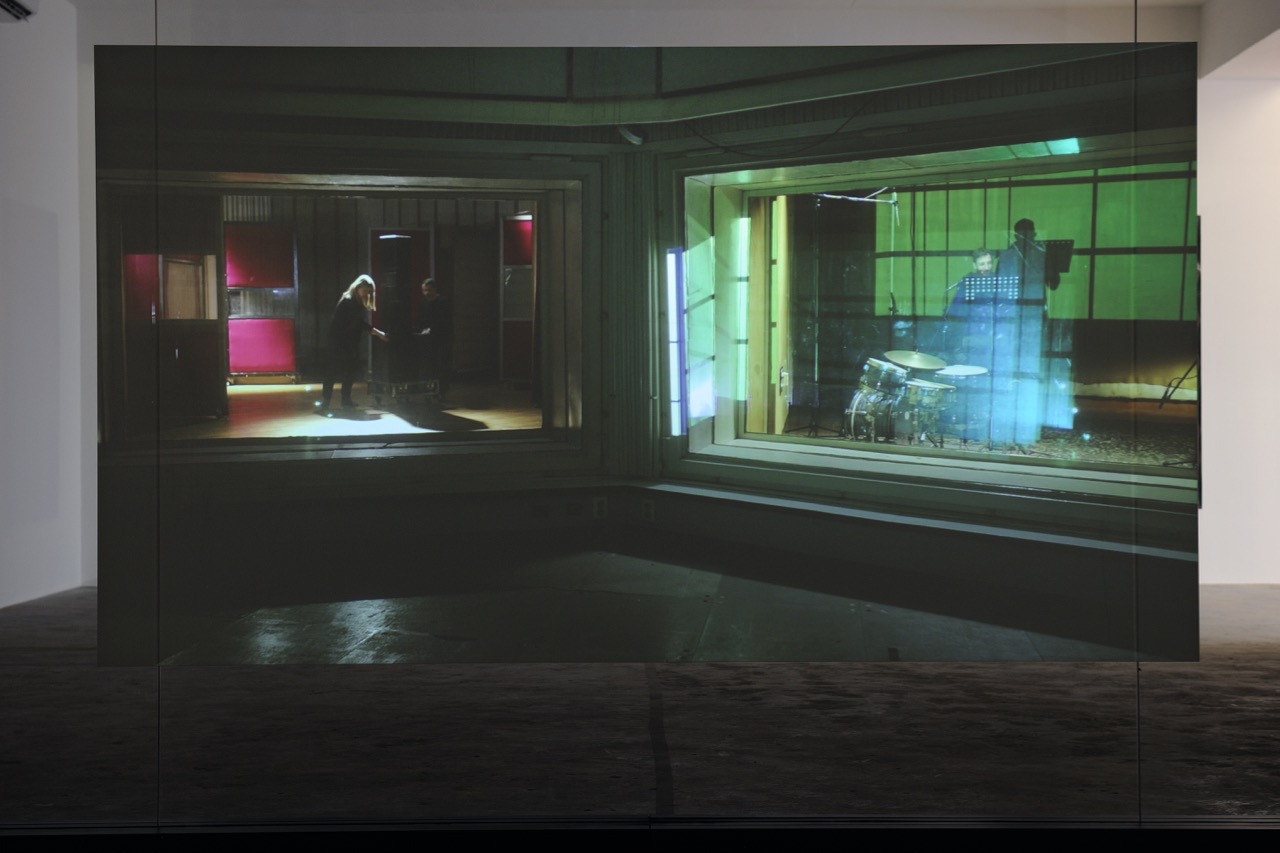

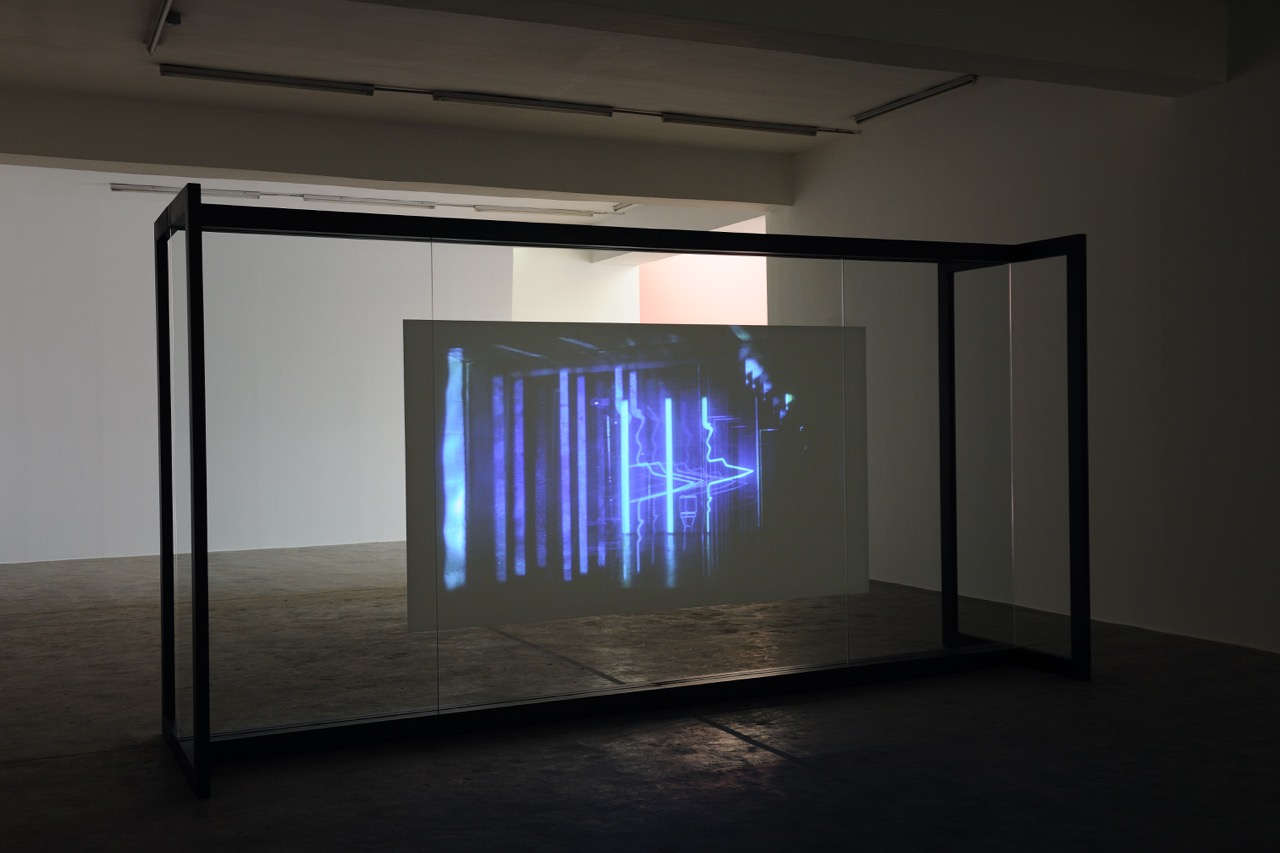

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Walled Unwalled, 2018. Single-channel video, color, sound, 20 minutes; installation with metal structure, glass, and foil. Wall design in collaboration with Müller Aprahamian. Image courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

The centerpiece of Natq is Walled Unwalled (2018), a video installation that pursues a political genealogy of wall building as it examines both the power and permeability of the physical thresholds that divide territories, restrict movement, and demarcate boundaries between public and private space. The twenty-minute video is projected onto special foil affixed to a glass wall, which refracts a mirror image of the video when viewed from the other side, and produces a translucency that embodies the thematic tension between the thickness and porousness of walls. In it one sees the artist wandering through padded recording studios reciting a text that is interspersed with audiovisual samples of Cold War propaganda broadcasts, legal testimonies, and—matched to the steady thudding of an on-screen drum set—the simulated sounds of prison torture.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Walled Unwalled, 2018. Single-channel video, color, sound, 20 minutes; installation with metal structure, glass, and foil. Wall design in collaboration with Müller Aprahamian. Image courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

Shot in Berlin’s Funkhaus—once the largest radio complex in the world and the broadcasting site for East Germany’s state radio networks—Walled Unwalled positions sound as a subversive agent, leaking through the Berlin Wall from both sides as Radio Free Europe sought to counter GDR propaganda and “pierce the Iron Curtain with truth.” Abu Hamdan entwines the story of dueling Cold War transmissions with his research on the sounds of Saydnaya (a building, we learn, that was modeled on GDR architecture) and two legal cases: the trial of South African athlete Oscar Pistorius for shooting his girlfriend through a door; and a Supreme Court argument concerning Oregon police’s use of thermal imaging to detect marijuana cultivation inside a private home they did not have a warrant to enter.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Walled Unwalled, 2018. Single-channel video, color, sound, 20 minutes; installation with metal structure, glass, and foil. Wall design in collaboration with Müller Aprahamian. Image courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

Walled Unwalled’s virtuosic monologue brilliantly scrutinizes the acoustic and microscopic vulnerabilities of walls even as it narrates the contemporary tragedy of hardening state borders and relates the horrors of torture in Saydnaya. It also finds moments of absurd levity. The weed dealer’s product was so potent it allegedly led one consumer to remark, as viewers of Abu Hamdan’s piece will: “I no longer know what a wall is.” Simply put, Walled Unwalled is one of the finest essay-films, performances, and installations in recent years—analytically sharp, formally stunning, and as poetic as it is timely and engaging.

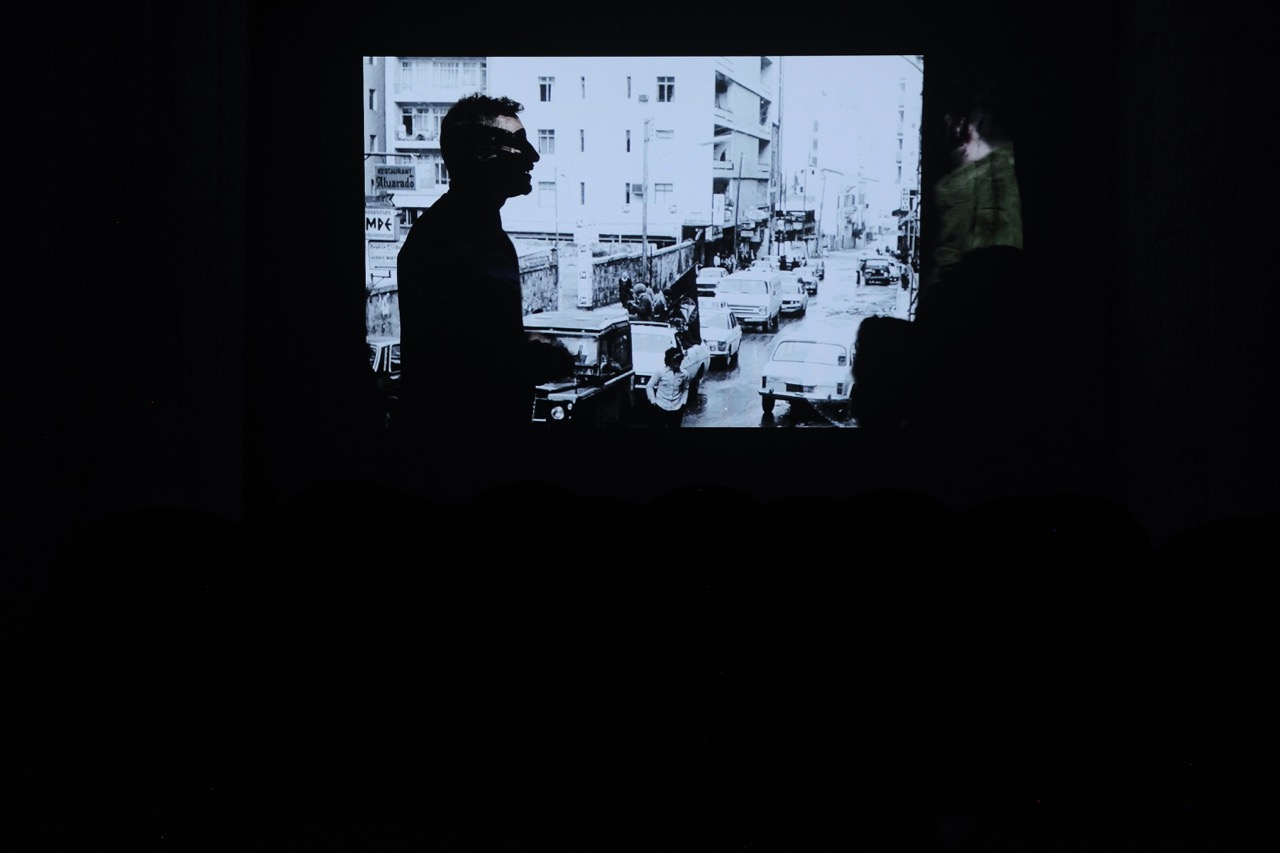

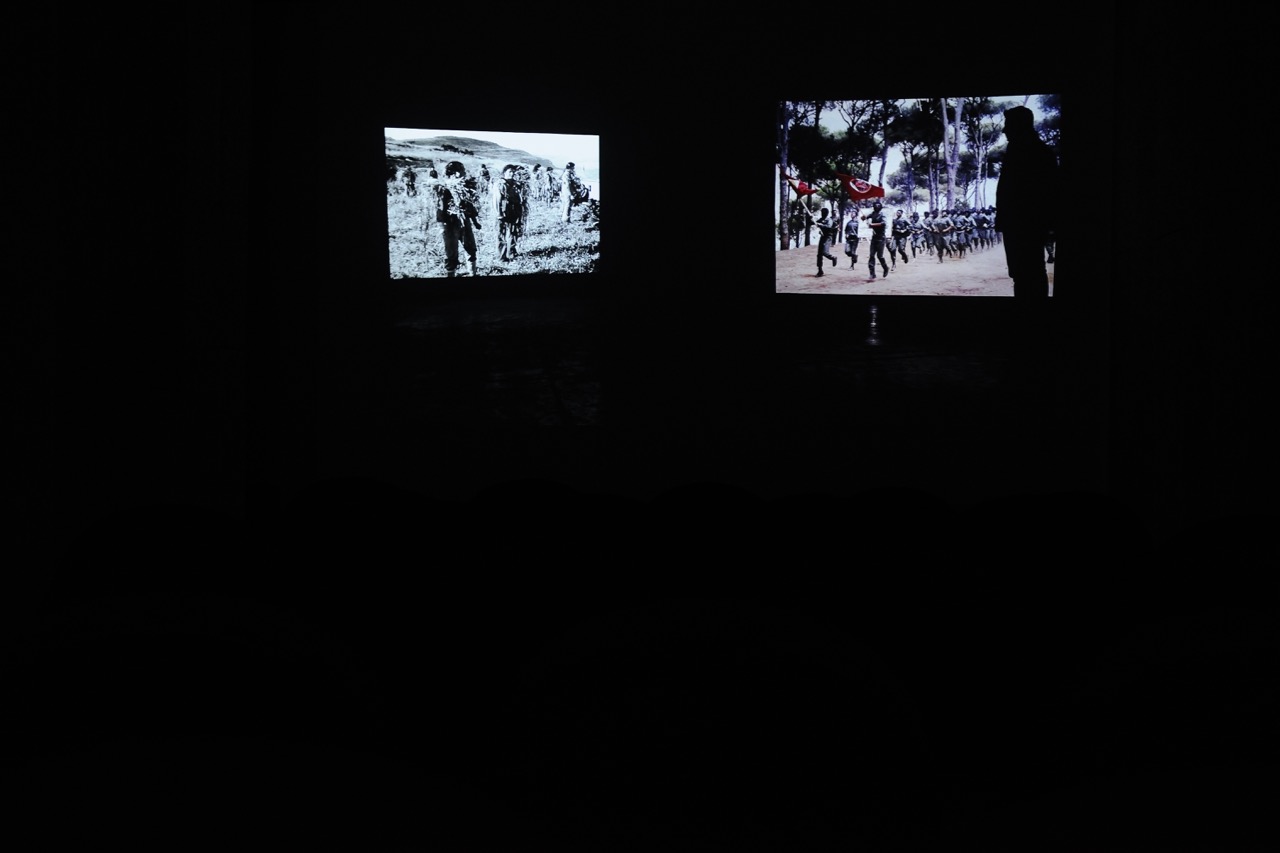

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Once Removed, 2019. HD video, color, sound, 28 minutes. Image courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

Departing from the Saydnaya-related material and even the artist’s primary interest in sound, two recent works in Natq reveal an unexpected but welcome research direction into the belief in reincarnation, especially among the Druze (a minority Muslim sect in the Levant). The twenty-eight-minute video Once Removed (2019) documents the fantastic story of Bassel Abi Chahine, who claims to remember his previous life as a soldier of the Lebanese Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) who died in 1984, at age sixteen, during the Lebanese civil war. Abu Hamdan interviews the soft-spoken, pensive Abi Chahine, born 1987, about his extensive research into this past identity and the communal histories of which he was part, as the two are filmed in silhouette, standing in front of projection screens onto which are projected photographs and pictures of artifacts from that era collected by Abi Chahine. As Abu Hamdan notes, these photographs are rare (and sometimes incriminating) documents; Abi Chahine has obtained exceptional access to them only because his claim to be the PSP soldier has been accepted by the latter’s family and community. His photographic archive, and the memories he narrates with an eerie mixture of intimacy and distance, opens a lens onto little-known scenes of the Lebanese civil war; poignantly, this material reanimation of a suppressed past attains a significance both intertwined with and independent of the alleged reincarnation of a Lebanese Druze soldier.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Once Removed, 2019. HD video, color, sound, 28 minutes. Image courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

In some respects, and unlike any of Abu Hamdan’s previous works, Once Removed echoes the practices of certain Lebanese artists of the “war generation”—Akram Zaatari, Rabih Mroué, Walid Raad (all represented by Sfeir-Semler)—who have been celebrated for unearthing civil war histories, constructing and deconstructing photographic archives, and combining the personal, the political, and the parafictional in experimental documentaries and lecture-performances. It too could be labeled parafiction, except Abu Hamdan is inventing nothing; it is the paranormal paired with the documentary that lends this work a strikingly oblique relationship to the real.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, For the Otherwise Unaccounted, 2019. Rubbings transfered on wooden panels, wall text, 35.4 × 168.5 inches, in 2 parts, each 35.4 × 84.25 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery.

Similarly, For the Otherwise Unaccounted (2019) methodically catalogs signs of the supernatural as Abu Hamdan parses the research of an American psychiatrist, Dr. Ian Stevenson, whose fieldwork in communities across Asia, Africa, and the Americas led him to conclude that the shape of birthmarks on reincarnated subjects correlated with their causes of death in previous lives. Abu Hamdan displays transfer prints of abstract shapes—ovals, lines, dots, splotches—representing these birthmarks in a line that leads toward an adjacent wall. There one finds a rectangular chart the size of an average person, hung vertically on the wall to underscore its physical association with the viewer’s body. Like a blown-up Microsoft Excel sheet with columns for such categories as “place and year of birth,” “previous personality,” and “status of investigation,” the chart organizes data from Stevenson’s research according to the location of birthmarks on the reincarnated subjects’ bodies, from head to toe. While the piece does not have the formal complexity or affective pull of Abu Hamdan’s audiovisual installations and performances, it offers subtle insights and pleasures, demonstrating how an archive of research on reincarnation doubles as an itinerant inventory of lives and deaths across the Global South—a poetic constellation and political collectivity weaved together as if by the unruliest algorithm.

A heterodox research question is always a more powerful motor for Abu Hamdan’s artistic practice than any software he employs. Technologically literate as Abu Hamdan’s investigations are, his art is predicated on a refusal to cede perception—and particularly listening—to artificial intelligence. For even our senses, as Walter Benjamin famously argued in his “Artwork” essay nearly a century ago, are conditioned by the social, political, and commercial forces that make our world. In the acoustic memories of Syrian political prisoners or a doctor’s examination of birthmarks, we do not reach a perfectly apprehended truth, but something more valuable: evidence that leads us equally to the material testimony of objects and to the poetics and politics of subjectivity.

Kareem Estefan is a writer, editor, and PhD candidate in Modern Culture and Media at Brown University, currently teaching media studies at the American University of Beirut. His art criticism has appeared in Art in America, BOMB, frieze, Ibraaz, Third Text, and the New Inquiry, among other publications. He is coeditor of Assuming Boycott: Resistance, Agency, and Cultural Production (OR Books, 2017).