Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Biological minutiae loom large in the artist’s exhibition of

sixteen cryptic paintings.

Anicka Yi: ÄLñ§ñ, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

Anicka Yi: ÄLñ§ñ, Gladstone Gallery, 515 West Twenty-Fourth Street, New York City, through November 12, 2022

• • •

“I’d like you all to meet my aerobe friend,” Anicka Yi says, gesturing to a towering creature—a translucent balloon with five undulating mechanical legs or fins—waiting in the wings. The kinetic sculpture, programmed to learn and interact with others, rises with a quiet whirring and floats across the ultramarine abyss of the TED-talk stage before touching down behind her to audience applause. (The presentation was taped in April, following the close of her exhibition In Love with the World, which featured twelve aerobes in an aquarium-like installation, or ecosystem, at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall.)

The landing is a cinematic moment, a dramatic introduction to an art practice that mirrors the forms and symbiotic relationships of living organisms. Yi explains she hopes to counter a technological era that fosters fear and alienation, to explore an alternate vision for machine evolution. Any strain of futurism today, though, however hopeful, strikes a dystopian note, and it’s doubtful that the artist, whose work is often a vehicle for sharp social critique, is trying in earnest to shake that shadow of foreboding entirely off.

Anicka Yi: ÄLñ§ñ, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

In her TED talk, Yi seeks to connect with a broad public, introducing a prototype for human-robot companionship, but cannot or does not fully extricate her “friend” from the associations of the drone technology it employs or of adjacent sci-fi narratives of AI gone awry. And in her new painting show at Gladstone Gallery, ÄLñ§ñ (pronounced “Alien Ocean”), a very different endeavor, a much vaguer, fugitive aesthetic of menace pervades.

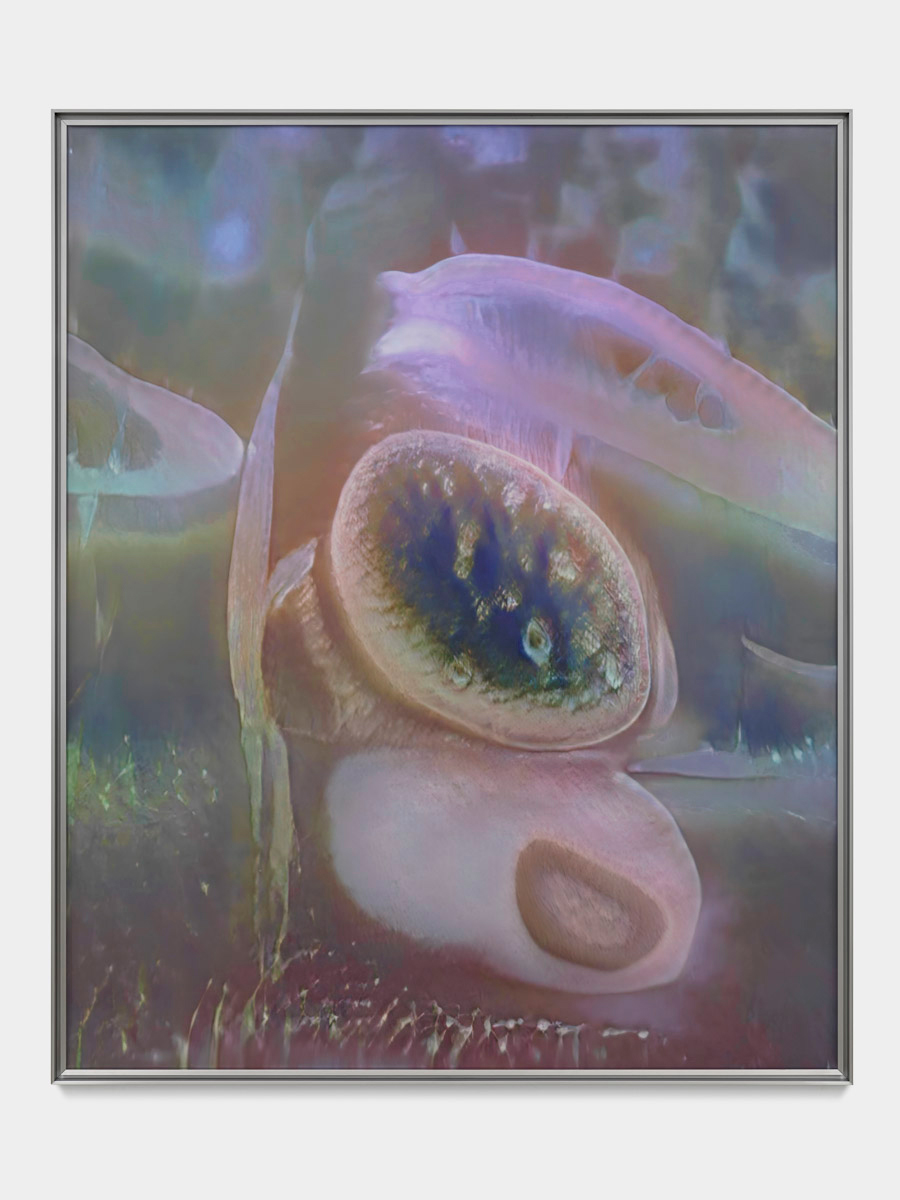

Sixteen large-scale canvases, uniform in size and vertical orientation, in aluminum frames, all dated 2022, bear titles (like that of the exhibition) written in an alphabet of symbol-phonemes. Abstract imagery rendered in earth and jewel tones recalls cells, ova, algae, and clouds of mycelia (fish eggs, ruptured derma, polyps, and crustaceans are mentioned in the press release). The natural world’s mix of ragged symmetry, randomness, and structural rhythm is unmistakable, but radical magnification—the microscope’s chilly rendering of wondrous or deadly detail—is a defamiliarizing force.

Anicka Yi, §M§†RñJR§, 2022. Acrylic, UV print, aluminum artist’s frame, 67 1/4 × 55 1/4 × 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

The paintings are mystifying as objects, too; Yi gives few details about her process. They have a multilayered construction, with (I think) a photographic substrate and at least one sheet of transparent mesh or vellum overlay, which is not flush with the surface beneath it. (On the checklist, the only materials listed are acrylic and UV print.) This screen or skin lends each of the compositions an aqueous depth and a veiled, membranous finish. Tinted areas, outlined shapes, and gestural marks disappear when seen from the front and seem to float, shift, and change color slightly as the viewer moves—a slippery, holographic effect.

Anicka Yi: ÄLñ§ñ, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

A late-September Instagram post is more forthcoming about the artist’s intent than the gallery press materials. The photo—a hand clad in a disposable blue glove holding a brittle fragment of transparent material, dotted with what looks like mold—is accompanied by Yi’s announcement of the Gladstone show and some context for the unusual (for her) body of work. “I didn’t go to art school so for me painting was the gilded gatekeeping medium to police all other art mediums,” she writes. “How does one even enter this loaded history?”

Anicka Yi, †R†W†R§†0WRK, 2022. Acrylic, UV print, aluminum artist’s frame, 67 1/4 × 55 1/4 × 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

I know what she means, but I’d answer, thinking of her career, that she already has: in previous painting-like works, the artist has used unstable, organic ingredients rather than representing them. Her Hugo Boss Prize exhibition, Life Is Cheap, at the Guggenheim in 2017 included an installation of agar gel tiles blooming with cultured bacteria, its samples collected from sites in Chinatown and Koreatown in Manhattan. In her survey Metaspore, which closed in August, at the Milanese postindustrial space Pirelli HangarBicocca, hanging slablike vitrines of local soil nodded to the landscape genre, drawing horizon lines and mountain ranges with serendipitously shaped swaths of colonizing microbes. It’s true, though, that ÄLñ§ñ engages more explicitly with specific historical styles (Abstract Expressionism and biomorphic abstraction, especially); in moments, canonical varieties of painterly beauty parallel the visual magnificence of biological minutiae—the pathos of petri-dish, tide-pool, or intracellular events.

Anicka Yi, ÈK×MR, 2022. Acrylic, UV print, aluminum artist’s frame, 67 1/4 × 55 1/4 × 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

In the gruesomely handsome ÈK×MR, livid brown-black and crimson masses hover together, or sink slowly, as platelet-like blobs break away—this one, and a few others, can be seen as brooding mutated additions to the lineage of Joan Miró. The inky cliff of †R†W†R§†0WRK seems geological or fungal in nature, but its stark lines also resemble a mid-century brush’s slashes and drips. And §£†§þ† might be a Helen Frankenthaler, with its bleeding pools of blue. Yi proficiently assembles—or draws out of her source material—a network of references that establishes her paintings as participants in a medium-specific meta-discourse. It is perhaps exciting terrain for her, but not so much for those who look at contemporary painting all the time, who see a lot of clever entrances into its loaded history, viewers like me.

Anicka Yi, §£†§þ†, 2022. Acrylic, UV print, aluminum artist’s frame, 67 1/4 × 55 1/4 × 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

Curiously, the artist developed these 2D works, which seem so formally staid and conceptually evasive in contrast to In Love with the World, while that epic project was in production. The turn to painting is a weird, maybe contrarian, move for someone whose most memorable pieces have challenged the status of the art object as static and nonliving as well as the primacy of the ocular in art. Olfactory elements have been a hallmark of Yi’s unpredictable practice, used to leverage the symbolic power of airborne dispersal, to toy with patriarchal and xenophobic fears of contamination, and to engage a sense generally regarded as outside the purview of art. At Turbine Hall, her two species of aerobe were accompanied by a series of scents inspired by the history of the cavernous London site on the bank of the River Thames—odors referencing the marine life of the Precambrian period, the Black Death, and the Industrial Revolution.

Anicka Yi: ÄLñ§ñ, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging. © Anicka Yi.

Walking through ÄLñ§ñ, Yi’s first commercial solo gallery show in New York in nearly a decade, I was reminded of a piece from 2015, from her exhibition at the Kitchen, for which a custom-crafted scent, based on the smell of mega-gallery Gagosian, was diffused in the venerable, alternative nonprofit space. But Gladstone’s newly expanded Chelsea gallery smelled like art during my visit, like nothing really; the acrylic paintings didn’t even exude oil’s seductive, history-laden, linseed-and-mineral poison stink. Perhaps they stand in relation to her more visionary work as a complementary exercise, emerging from a purposefully retrograde, ironic approach. But, aloof and super cryptic, they leave an impression primarily of elegance and polish. That said, it wouldn’t shock me to learn that a critique of both the hallowed medium and the blue-chip space—of gilded gatekeeping—lurks beneath.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum.