Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

An exhibition commemorates a pivotal moment in the

gay rights movement.

Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989, installation view at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art. Image courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum.

Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989, Grey Art Gallery, New York University, 100 Washington Square East, New York City, through July 20, 2019; and the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, 26 Wooster Street, New York City, through July 21, 2019

• • •

If you walk by the Stonewall Inn regularly, it can become just another gay bar, notable mostly for its scrappy endurance in the gentrified-beyond-belief West Village. With its three-and-a-half-star Yelp rating and window-box cages decorated with little rainbow flags, snuggled next to QQ Nails & Spa on Christopher Street, it’s an unlikely national monument—a designation bestowed by President Obama in a strangely distant time, not three years ago. There is a holographic quality to the unassuming Stonewall, though; a double image from the past is always there if you look. When LGBT out-of-towners stop on their walking tours to gaze at its brick façade, when the small park and streets around it fill—as they did with revelers celebrating the Supreme Court same-sex marriage ruling in 2015, and the next year with mourners for the fifty-nine victims of the Orlando Pulse shooting—the mythic emerges from the mundane.

“This place was the ‘ART’ that gave form to the feelings of our heartbeats,” Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt wrote, in 1989, in his handwritten broadsheet Mother Stonewall and the Golden Rats, remembering the bar on that historic June night, two decades earlier, when its queer, trans, multiracial, gender-nonconforming, sex-worker, homeless patrons, their dancing interrupted by a raid, fought the police and destroyed everything in sight. Just as Jesus was born in a manger, Lanigan-Schmidt reflected in Mother, “the mystery of history happened again in the least likely of places.” Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989, an epic exhibition staged in honor of the uprising’s fiftieth anniversary, features Lanigan-Schmidt’s poetic text at both its locations, printed on sheets of festive neon paper for visitors to take. Curators Jonathan Weinberg, Tyler Cann, and Drew Sawyer thus frame “Stonewall” as not the anodyne origin story of the mainstream gay rights movement, but as an insurgent, generative gesture of all-caps ART that reverberates through the wild variety of works on view. The first half of the roughly chronological show is installed at the Leslie-Lohman Museum; NYU’s Grey Art Gallery presents the 1980s.

Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989, installation view at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art. Image courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum.

A wealth of exhilarating photos captures the heady first years of the gay liberation movement, while paintings include such wonders as Lula Mae Blocton’s dusky pastel geometric abstraction Summer Ease (1975), David Hockney’s loosely rendered portrait of Divine (1979), and Martin Wong’s Big Heat (1988), which shows two firemen kissing before a smoldering tenement building. Greer Lankton’s long-legged, hand-sewn dolls from the 1980s are unforgettable with their harsh but charming frozen faces; Robert Gober’s Untitled Closet (1989) is just what it sounds like, a person-sized space recessed into the gallery wall, empty, with no door to close behind you. Some straight artists appear, too—Alice Neel, Vito Acconci, Barkley L. Hendricks—illustrating the profound influence of gay liberation on avant-garde aesthetics in general. Altogether, the visual hubbub recalls the cacophony of a spirited community meeting—one that can be quieted for a moment of silence, though.

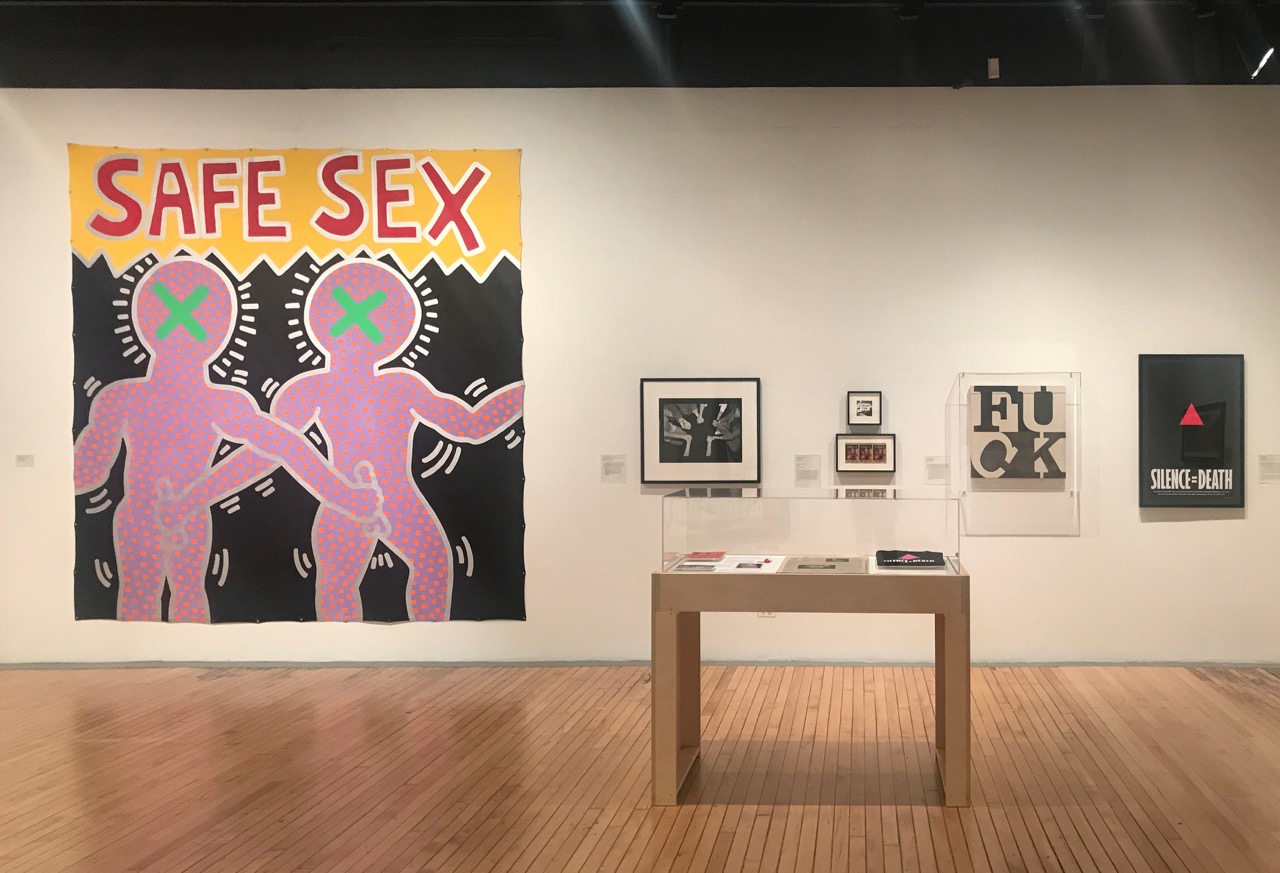

Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989, installation view at Grey Art Gallery, New York University. Image courtesy Grey Art Gallery, NYU.

A portrait of the hero of lesbian filmmaking, Barbara Hammer, who died in March, is positioned at the entrance to the Leslie-Lohman. Mickalene Thomas’s photo of the artist, taken this year, shows her wearing motorcycle goggles—or rather marked with their silhouette, rendered in red pigment—as though suited up, symbolically, for the adventure of death. (The artist, in her final years, made living with terminal cancer a subject of her art.) Inside, her early groundbreaking 16mm short film Dyketactics (1974), an erotic reverie conceived of as a “commercial” for lesbianism, loops on a monitor. While works such as Tee A. Corinne’s photography-based kaleidoscopic abstractions echo the joyous gynocentricity of Hammer’s grainy montage, a strength of this exhibition is its purposeful erosion of historical aesthetic-ideological divides: Michela Griffo’s canvas My Funny Valentine (1979), installed quite close to Hammer’s film, features a vignette borrowed from porn. The painter’s careful pencil rendering of two women making out in fetish gear unapologetically enlists the presumptively male gaze that the filmmaker and others sought to banish.

Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989, installation view at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art. Image courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum.

Vexingly, responsibly, or ingeniously—I can’t decide—the cis white male curatorial team invokes Audre Lorde’s landmark essay “The Uses of the Erotic” (1978) to identify the creative power of sexuality as it appears so strikingly throughout the show. The poet’s treatise on the “replenishing and provocative force” of the erotic, which has been “misnamed by men and used against women,” is, in After Stonewall, expanded “to think about the ways queer artists of all genders tap desire as a rich source,” the wall text explains. While a conceptual liberty has been taken by the curators, the suggestion that we consider the survey’s abundant sexual content through a black lesbian lens is intriguing. How do Alvin Baltrop’s gorgeous, moody scenes of men sunbathing and cruising on the abandoned Hudson River piers in the 1970s, the neo-expressionist figures jerking each other off in Keith Haring’s large-scale painting Safe Sex (1985), and the austerely formal S-M portraits from Robert Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio (1978) withstand or benefit from her critique of white patriarchal repression? The invocation of Lorde’s legacy achieves a subtle decentering consistent with the show’s many efforts to correct the record where it’s been distorted by the biases of the art world, the larger culture—and a gay rights movement that has too often forsaken the very “golden rats” who risked everything to start it.

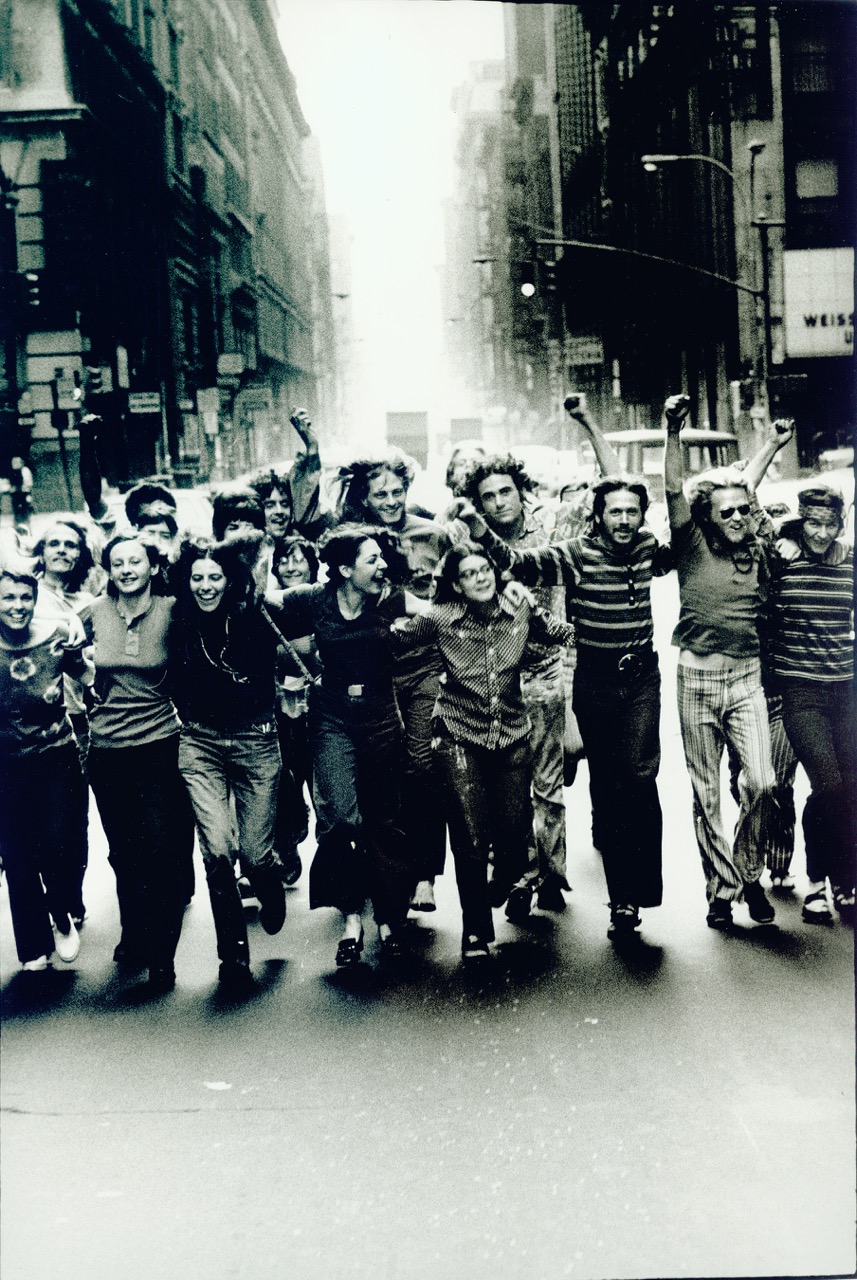

Peter Hujar, Gay Liberation Front poster image, 1970. Vintage gelatin silver print, 18 × 12 inches. Image courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum.

The curators point out, for example, in their wall labels, that Peter Hujar’s iconic image of triumphant marchers taking over the street with raised fists, used for the Gay Liberation Front’s Come Out!! poster in 1970, represented only young, white people; and that Andy Warhol’s 1975 silk-screen portrait of performer and trans-activist hero Marsha P. Johnson—an instigator of the Stonewall Riots and cofounder, with Sylvia Rivera, of the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries—fails to identify her by name. In methodically reestablishing the radical character of the LGBT movement’s start, and the precarious lives of its courageous protagonists, the exhibition deftly connects the uprising of 1969 to the AIDS activism of the 1980s. At the Grey Art Gallery this material—the designs that have forever set the standard for media-savvy agitprop—is represented by such numinous artifacts as the Silence=Death Project’s graphically and rhetorically precise pink-triangle-on-a-black-background poster of 1987, and Marlene McCarty’s spoof on Robert Indiana’s Love (1966). Her version, Love, AIDS, Riot (1989–90), spells out the expletive—and the demand for pleasure—FUCK.

Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989, installation view at Grey Art Gallery, New York University. Image courtesy Grey Art Gallery, NYU.

While no one wants to end on a tragic note, this exhibition stops at 1989, so it is what it is. Reading the names on the wall labels and turning the pages of the show’s beautiful, substantial catalog, you can’t help but pause, frequently, thinking of how many of these artists were lost to AIDS. Yet Art after Stonewall, with its unruly mix of objects, ephemera, and ideas, gracefully makes space for elegiac moments as it celebrates the birth of a movement. It’s a welcome tribute to the beloved dive that, consecrated a half-century ago with burning garbage, flying beer bottles, an uprooted parking meter, and a taunting chorus line of queens, still stands for the everyday entanglement of exultation and loss known as liberation.

Johanna Fateman is a writer and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She is coeditor of Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, published by Semiotext(e). She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a book.