Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Good vibrations: the artist offers up his assemblages and sound baths.

Guadalupe Maravilla: Seven Ancestral Stomachs, installation view. Courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W.

Guadalupe Maravilla: Seven Ancestral Stomachs, P.P.O.W, 392 Broadway, New York City, through March 27, 2021

• • •

As we pass the pandemic’s anniversary in partially vaccinated limbo, Guadalupe Maravilla’s Disease Throwers, with their thrilling name and numinous glamour, in his new exhibition at P.P.O.W, feel full of springtime promise as symbols—or summoners—of renewal and protection. I felt that way, certainly, lying limp and rapt on the gallery floor while the artist played them. The “healing machines,” as he describes the imposing assemblage works featured in Seven Ancestral Stomachs, are instruments; each has, at its heart, a gong.

Maravilla credits the therapeutic effects of their sonorous vibrations with aiding his own recovery from trauma and grave illness, and his sound baths have become central to an expansive aesthetic and spiritual practice, both private and communal, that moves beyond the bounds of conventional art-world venues and audiences—which is not to say his objects and performances don’t scale or translate beautifully to a gallery setting.

Guadalupe Maravilla, Disease Thrower #3, 2019. Mixed media sculpture, 96 × 57 × 63 inches. Courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W.

The six freestanding Disease Throwers, which were made in 2019 and 2020, and range in height from eight to fifteen feet, together form a staggered procession, beginning with #3 in the window of the gallery’s new Tribeca storefront space. The five others fill the high-ceilinged main room. They’re not the only works on view—two other, smaller series in their orbit, and a sprawling drawing that traverses the walls, are key to the installation’s ambience and unfolding story. But the grand gong works are the exhibition’s benevolent/fearsome protagonists.

Guadalupe Maravilla: Seven Ancestral Stomachs, installation view. Courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W.

All manner of found objects (toy snakes, plastic anatomical models, baskets, and conch shells among them) join zigzagging pieces of metal and an array of plant matter (including long serpentine loofahs, corn husks, and reeds), stiffened by a pale, experimental material, created by the artist, to form the sculptures’ lumpily ornate armatures. The symbolically dense hybrids are ghostly and arboreal, while also evoking mythic beasts: they rest Sphinx-like on clawed legs sometimes, and their gongs look like cyclopean eyes. For the sound bath, we gathered—socially distanced—on woven blankets at their feet. (The sessions are scheduled for Thursday and Friday evenings, with a virtual version offered Sunday afternoon, March 21.)

Guadalupe Maravilla, Disease Thrower #7, 2019 (detail). Mixed media sculpture, 180 × 96 × 63 inches. Courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W.

The instruments more than hold their own as sculptures, but they have additional functions, too. They can be used as fantastic headdresses (adjustable bands, detached from what looks like a helmet interior, are visible beneath at least one Disease Thrower’s chassis). They’re also shrines. When left alone, quiet and still, they have the special magnetism and intimate air of devotional objects invested with tremendous personal, autobiographical significance.

In the 1980s, Maravilla was among the unaccompanied children who left El Salvador for the United States during the Salvadoran Civil War. He remained undocumented until the age of twenty-six, and a decade later he was diagnosed with stage-three colon cancer. Much of the found material incorporated into his sculptures is from the Central American route that he traveled, for two and a half months, as an eight-year-old, handed from coyote to coyote. He collected the exacting jumble of things that adorn his Disease Throwers as an adult when he revisited the towns and villages he passed through decades ago—a healing journey undertaken to face the trauma of his migration and its long-term repercussions for his health. More than simply mementos, these found objects, both natural and manufactured, are talismanic and protective. “Rivers have energy; the rock, the tree, and the little birds have energy. And a plastic chair or a ’90s Bart Simpson shirt have energy just like the toad on the pond,” Maravilla says in explaining how his art, his syncretic spirituality, and his healing modalities draw upon the animism of his Mayan ancestry and the beliefs of other indigenous cultures.

Guadalupe Maravilla, Ancestral Stomach 2, 2021. Dried gourd with mixed media, 26 × 24 3/4 × 13 inches. Courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W.

One such belief—that it’s possible, in a single lifetime, to heal seven generations forward, as well as back, into the past—inspires the seven-part title series of the show. Installed to ring the Disease Throwers, each Ancestral Stomach (all 2021) is a wall-based sculptures assembled around twisted, bulbous dried gourds that resemble the digestive organs the compositions are named for. Gnarled, nest-like, and fitted with talons, the Stomachs seem to speak of abdominal pain as well as, perhaps, avian guardians.

A balance of direct, poetic imagery and free-form emotional intensity lend them an unresolved beauty, which is echoed and amplified by the maze- or intestine-like drawing that spreads across the gallery walls around them. The mural was made in a collaborative process derived from the Salvadoran children’s game tripa chuca (or “dirty guts”), in which two players take turns linking sets of scattered numbers; it quickly becomes tricky as no line can intersect with another. (Maravilla's mural omits the numbers.) Working (playing) together with an undocumented person, Maravilla reenacts, in an expanded, public form, a pastime that helped him cope as young boy, fleeing war for the unknown.

Guadalupe Maravilla: Seven Ancestral Stomachs, installation view. Courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W.

The impulse, or ethos, to connect with others, even—perhaps especially—as he mines what might be considered the most private and vulnerable of experiences, is defining. And while it suffuses every element of the exhibition, it’s never more explicit than in the group of eight small oil-on-tin works from 2021, rendered in the Central American votive tradition of the retablo. (They fill the back gallery.) Maravilla sent digital sketches to a fourth-generation retablo painter in Mexico to produce these exquisite and moving narrative works, some of which feature straightforward written accounts of his devastating and transformative experience with cancer. The text of Thank you Pixelated Goat Retablo, which shows a cropped image of a tattoo artist at work on Maravilla’s torso, overwriting surgery scars, reads (translated from Spanish), “I survived cancer thanks to my oncologist, my acupuncturist, a surgeon, shamans, healers and witches.”

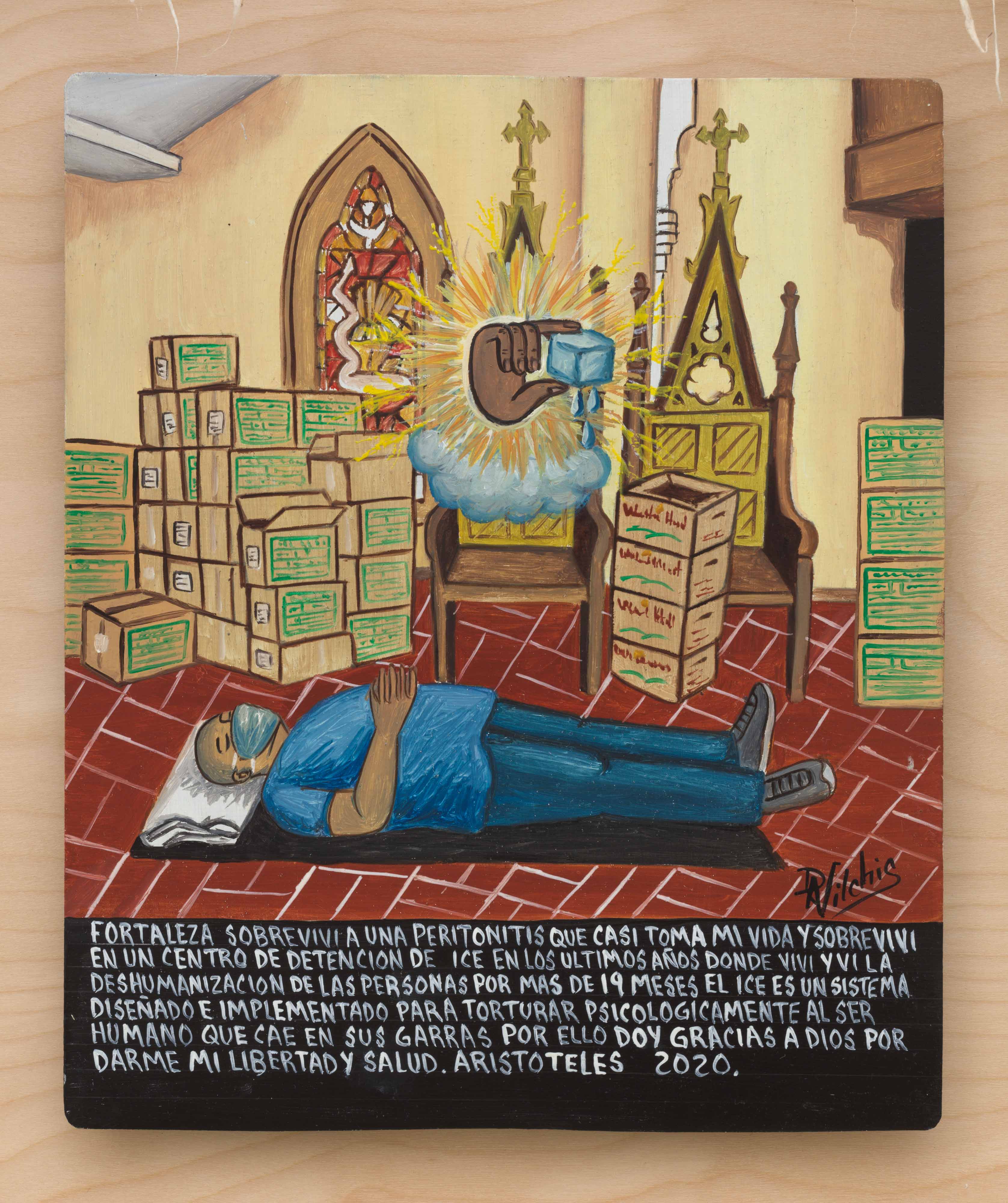

Guadalupe Maravilla, Aristoteles’ story about being detained by ICE Retablo, 2021 (detail). Oil on tin, mixed media on wood; 45 1/2 × 19 3/4 × 4 1/4 inches.

In another tableau, the artist describes his cancelation of a sound bath (with a thousand attendees expected) almost a year ago exactly due to the pandemic; in one more he explains how, during the dreadful first wave, he conducted healing events regularly for the undocumented community at a church in Brooklyn. In Aristoteles’ story about being detained by ICE Retablo, Aristoteles seems to be at one of those sound baths, lying on the floor, awash in vibrations with his eyes closed, surgical mask on. His words fill the painting’s bottom margin: “I survived a peritonitis infection that almost took my life while I was detained by ICE in recent years. While detained I lived and saw the dehumanization of people for more than 19 months.” Maravilla, by sharing another immigrant’s story, drives home his conviction that the traumas endemic to undocumented life can be expressed in the body as disease, the coronavirus—which has ravaged communities so unequally—adding a new, very dangerous stress.

On the warm night of March 11, when I returned to the gallery to see, or rather hear and feel, the artist’s Disease Throwers activated, Maravilla introduced the sound bath matter-of-factly, only briefly alluding to the heavy anniversary, our possible present turning point, and the mood of hesitant hope. The experience itself was ringing, thunderous, but also serene and low-key. While it’s too soon to tell the effects on my health, the hour-long event gloriously brought the show’s various elements together, making new sense of Marvilla’s work as a rare and important, remarkably generous kind of art.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.