Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

From Bennington to Hotel Cro-Magnon: a look at Helen Frankenthaler’s early years as an artist.

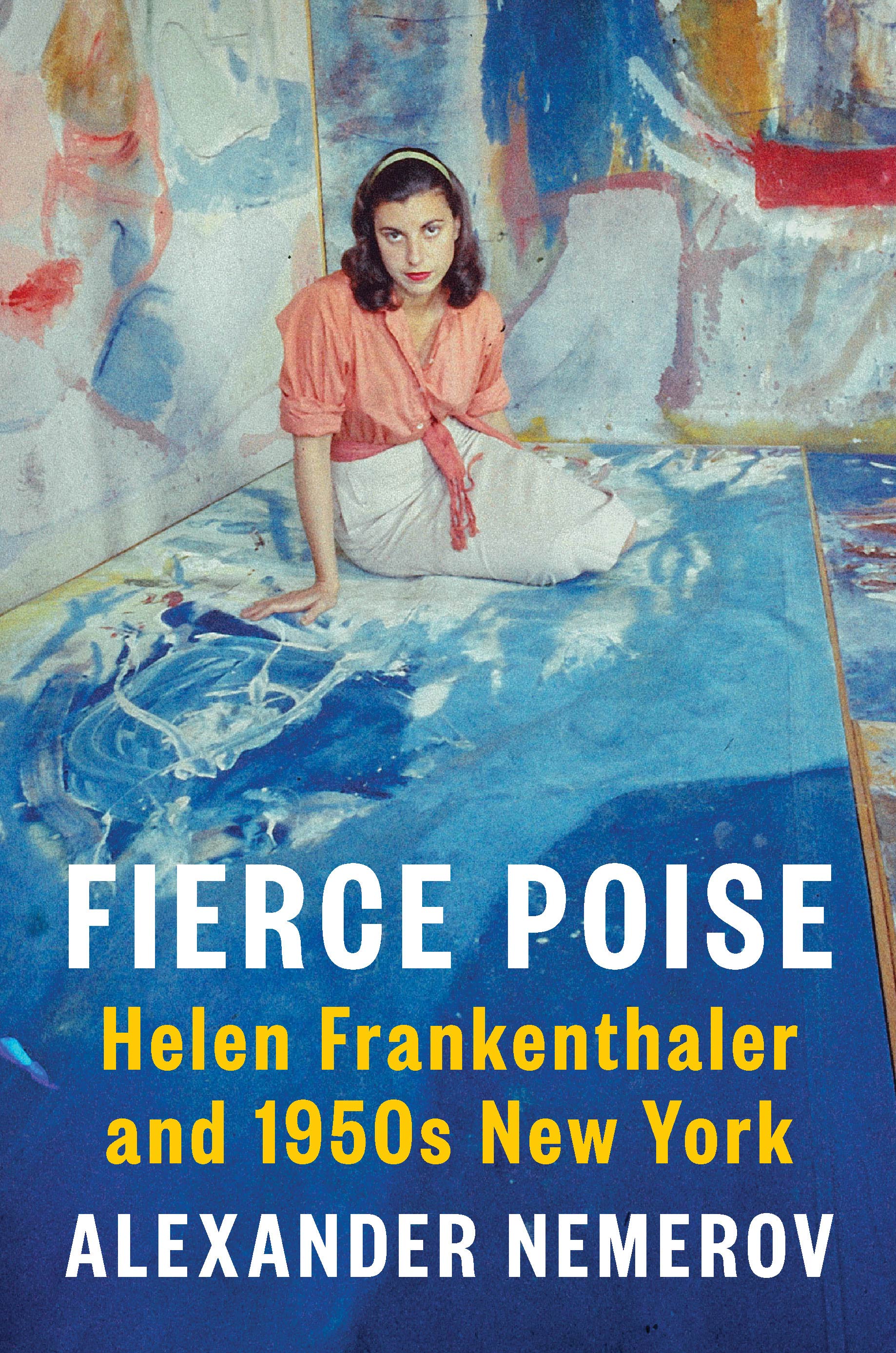

Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York,

by Alexander Nemerov, Penguin Press, 269 pages, $28

• • •

Among all the artists of the New York School, that brilliant and quarrelsome group of postwar painters and poets, Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011) stands out for the apparent ease of her artistic process. The youngest of the Abstract Expressionist painters, she flew through the tumultuous 1950s on her charm, family money, intense devotion to her art, and well-placed confidence in her talent. This causes a problem in the valuation of her work. Pollock, Rothko, Willem de Kooning must be good, because look what they paid in depression, alcoholism, and self-doubt. Frankenthaler’s stunning canvases challenge this equation and refuse its mean-spirited, capitalistic terms. Too pretty, too privileged, too much plain sailing? Who decides?

In Fierce Poise, his slim, thoughtful, and admiring book charting Frankenthaler’s first decade as an artist, art historian Alexander Nemerov describes how early she found her creative path. Twenty-one and fresh out of Bennington, she was still painting Cubist vases when she had a conversion moment, in 1950, walking into her first Pollock show. Astonished by the freedom of his drip paintings, she reveled in the permission his work gave her. She said his paintings “opened up what one’s own inventiveness could take off from.” Of one of her earliest abstractions, The Sightseers (1951), Nemerov writes that it “accepts the fragmentation” of life and “conveys the ecstasy of seeing the world, the joy of discovering that there is so much—too much—to see.”

The following year, Frankenthaler raised the stakes. Adopting Pollock’s innovation of working on the ground, she spread a seven-by-ten-foot piece of canvas on the floor of her studio, thinned her paints with turpentine to watercolor consistency, and poured them out of cans, letting the colors soak into the unprimed surface. The staining technique she invented that day would define her career.

Nemerov loves this famous first stained painting, titled Mountains and Sea. He calls it light, “honest,” “uninhibited,” “all apparent ease and nonchalance,” and imbued with a “brazen yet gentle freedom, [a] sense of art as a spilling out.” He argues for it as a secular Jewish painting, inspired by personal experience and eager to talk about it. He’s fascinated by its qualities, as he sees it, of private emotion and loud statement, its “mixture of diary and declamation.”

Alternating meditations on her work with scenes from her biography, Nemerov gives us Frankenthaler as a much-encouraged youngest daughter on the Upper East Side, spattering drops of her mother’s red nail polish in a sink full of water. Her childhood happiness ended with the death of her beloved father, when she was eleven. She spent the next years in miserable mourning, until her painting teacher at Dalton, the artist Rufino Tamayo, recognized the artistic gift that became her refuge.

He was the first of many nurturing father figures. (Nemerov’s own father, Howard Nemerov, was one of her English teachers at Bennington.) Unusually for a woman in the mid-twentieth century, Frankenthaler knew how to accept a man’s help without giving more for it than she could afford. Her date to that first Pollock show was Clement Greenberg, the most prominent art critic of the early ’50s. She was twenty-one to his forty-one, and during their six-year, on-and-off relationship he helped form her aesthetic judgment and invited her into his social circle, which included Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Willem and Elaine de Kooning. After she broke up with him, tired of his “relentless self-absorption,” refusal to commit, and increasing obtuseness as a critic, she inherited all of their mutual friends.

Nemerov might have included more about these mutual friends. He quotes from her correspondence but doesn’t bring her fellow artists alive as characters, the way Mary Gabriel does in her terrific (and much longer) history of the decade, Ninth Street Women. When Frankenthaler marries the older, established, independently wealthy painter Robert Motherwell in 1958, Nemerov writes interestingly about her attempts to be a stepmother but faintly disapproves of her patrician lifestyle.

Those old ideas about suffering and authenticity are lurking in the background of Fierce Poise, and so are some unexamined critical assessments of women’s art. Nemerov is writing as a fan, more than a critic, when he praises the “rapturous ugliness” and fleshy presence of Giralda and the “bright colors and fervid joy” of another 1956 canvas, Eden. He loves the “whirling exultation” of her abstractions inspired by a 1958 visit to Lascaux and Altamira, including Before the Caves and Hotel Cro-Magnon. (Frankenthaler had a special genius for titles.)

But her paintings, in his view, do a lot of “welling up” and “spilling out.” He frequently remarks on her emotionality, on how hers is “an art of immediate impressions. . . . of sensation.” Jacob’s Ladder (1957), which at ten feet tall is hardly a subtle statement, nonetheless contains “a melting and vulnerable softness as of feelings so delicate they can be stated only in whispers.” These female qualifications—sensuous, vulnerable, wet—bring him perilously close to Joan Mitchell’s much-quoted assessment of Frankenthaler as “that Kotex painter,” while his accounts of her life with Motherwell bring to mind Grace Hartigan’s jibe that her paintings looked like they were made “between cocktails and dinner.” The poet and critic Frank O’Hara, more balanced, observed that Frankenthaler could “risk everything on inspiration,” then judge the result with a “very keen and even erudite intelligence.”

Nemerov, as he says in his introduction, was a graduate student at Yale in the 1980s, when it definitely wasn’t OK to like something unironically, or to find pleasure in an artistic encounter. Back then he distrusted Frankenthaler (who supported the opposing side in the theory wars when she called Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano “mediocre”). Now he’s bravely making up for his lost theory years, yet in his responses to Frankenthaler’s “grace and beauty” he’s still reifying the divide between thoughts and emotions, being pretty and smart. It takes a profound creative intelligence to be joyful, but evidently that wasn’t the kind they valued at Yale. It’s hard not to suspect Nemerov, however fine his celebration of Frankenthaler’s work, of being another man asking a woman to do his feeling for him.

Julie Phillips is the award-winning author of James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon. She lives in Amsterdam and is working on a biographical book about creativity and mothering, for which she received a Whiting nonfiction grant. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Ms., and the Village Voice, among others. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.