Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Second-wave feminist films stand out in this expansive documentary series.

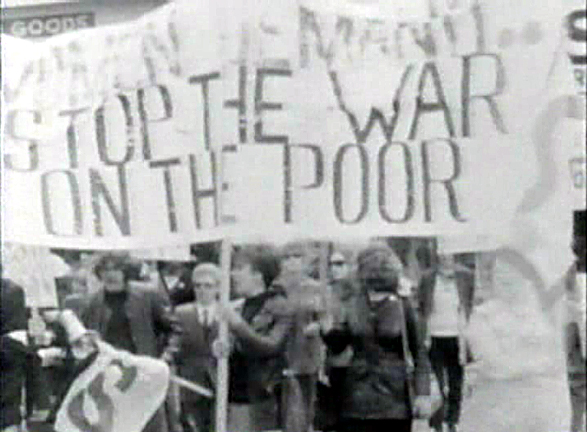

Still from Janie’s Janie. Image courtesy Third World Newsreel.

“Tell Me: Women Filmmakers, Women’s Stories,” Metrograph, 7 Ludlow Street, New York City, through February 11, 2018

• • •

In the astonishing film portrait Janie’s Janie (1971), directed by Geri Arthur with collaborators from the activist-oriented Newsreel collective, the unassuming, charismatic Jane Giese of Newark, New Jersey, rarely sits still. The camera follows her around a cramped kitchen as she puts groceries away, crouches to ignite the oven pilot light, or zips up her son’s jacket, a cigarette hanging from her mouth. The working-class mother tells her story matter-of-factly, of how she escaped her father’s beatings by getting pregnant at fifteen and marrying the boorish, absent Charlie, who also smacked her, because she “deserved it” when her “mouth got too fresh.” Raising her precisely penciled eyebrows, she adds acidly, “He should hear my mouth now. He should hear it now.” On her own with six kids, she scrapes by on welfare, and has joined the feminist revolution.

Arthur’s dynamic treatment of domestic space and her intimate depiction of Janie is echoed in many of the films in Metrograph’s unruly, rousing series “Tell Me: Women Filmmakers, Women’s Stories.” Programmer Nellie Killian’s selections, which span more than three decades and a wide range of documentary styles, include fascinating titles by directors with a palpable personal stake in their subjects. These filmmakers excavate family histories and individual traumas; amplify calls for justice; and defy conventional cinematic representations of women’s bodies, labor, and relationships. But it’s the blazing early works here, which are so closely aligned, in both subject matter and formal strategy, with the heady days of feminism’s second-wave, that seem essential viewing now—as startling documents from an era of momentous, hard-won gains, and as bold precursors to the weaponized candor moving mountains today.

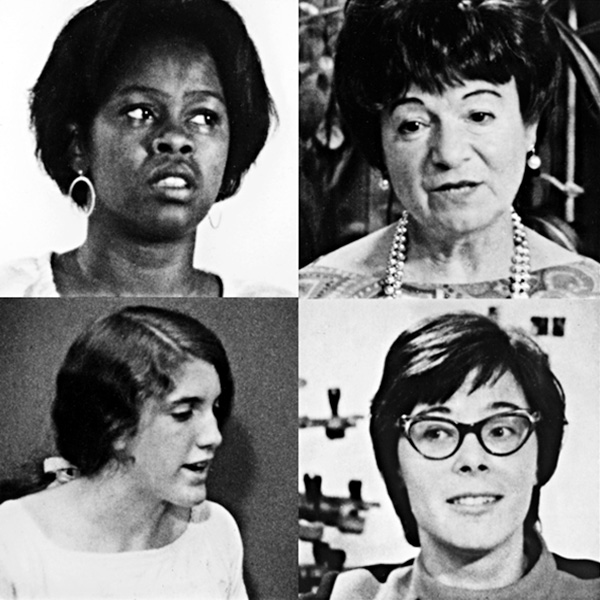

Still from The Woman’s Film. Image courtesy Third World Newsreel.

The consciousness-raising group, which emerged in the late sixties as the fundamental organizing tool of the women’s movement, looms large in these films. The Woman’s Film, also from 1971, made collectively by the women of San Francisco Newsreel, was shot largely in living rooms across America, capturing a historic opening of the floodgates. Women speak frankly and angrily about miserable marriages, interminable housework, job discrimination, racism, and sexual harassment—emboldened by the earth-shaking realization that in recounting their so-called personal problems, they are contributing to the analysis of a shared political condition.

There’s CR group footage in Janie, too. We see her at a meeting with her back-combed, decidedly non-countercultural hairstyle, smoking thoughtfully on a folding chair. Over shots of the diverse gathering, she explains how, as a white woman, she’s found common cause with the other poor mothers in her neighborhood, challenging the racist attitudes she was raised with in order to start a community daycare center with them. In this context, it makes sense why Janie would open her chaotic home to a film crew without apparent embarrassment, or allow them to trail her to the public-assistance office. The CR ethos had tremendous implications for filmmaking, for women on either side of the camera. There was a real political benefit to representing women’s lives as truthfully as possible.

The image of consciousness-raising as merely a therapeutic technique irritated its radical inventors. Women shared the harrowing, humiliating details of their individual hells not to get them off their chests, but because the movement needed this grassroots collection of raw intelligence, free from patriarchal tampering, to figure out what to do. The feminist struggle to legalize abortion is testament to how strategically effective CR groups could be. It wasn’t until the movement created a space and a culture of solidarity for personal-political self-exposure that feminists could get a head count of those in their own circle who’d broken the law and risked their lives to terminate pregnancies. On the basis of the staggering numbers and horrific stories, they could then mobilize.

Still from It Happens to Us. Image courtesy New Day Films.

It Happens to Us, made in 1971, by Amalie R. Rothschild, is a simple, beautifully shot film that both incorporates living-room footage of women discussing abortion and mirrors the “around the room” format of CR groups in its organization of interview footage. Released in 1972, the year before the Supreme Court ruling that would legalize abortion, it’s a snapshot of a radical movement on the verge of victory—and a no-holds-barred work of feminist agitprop. Its devastating opening scene could stand alone, and should be watched today by anyone unclear on what a bloody, cataclysmic triumph for fascism a repeal of Roe v. Wade would constitute. A young woman from Knoxville, Tennessee, sits alone by a sunny window and very quietly tells her heartbreaking and gruesome story of a clandestine abortion and its aftermath; the camera moves in closer and closer as it becomes more difficult to listen. In what follows, Rothschild doesn’t present a reel of atrocities; It Happens to Us is a concise argument, woven from personal accounts and medically accurate information.

Still from To Love, Honor and Obey. Image courtesy Third World Newsreel.

Filmmakers Christine Choy and Marlene Dann do, in a sense, present a reel of atrocities in To Love, Honor and Obey (1980), which is not to say their treatment of domestic violence, the subject of this nearly hour-long documentary, is prurient. Here, there’s no honest way around a frank indexing of physical and emotional torments. Though the directors are more traditional, or sociological, in their approach—interviewing cops, doctors, lawyers, social workers, and male abusers—their roots in feminist praxis are clear. Unsparing accounts of cruelty and terror from survivors of intimate partner abuse—the real experts on the issue—are used to bring the historically invisible epidemic to light. Remarkable footage shot at the Hackensack, New Jersey, battered women’s shelter SOS (Shelter Our Sisters), founded by Sandra Ramos seven years after she first opened her home to families in need of refuge, in 1970, illuminates the radical, scrappy roots of the battered-women’s movement. We get a glimpse of a weary Ramos answering a crisis call from a woman who’s fled with her kids after she was threatened with a knife (“OK, we’ll be there in a few minutes. Can you keep out of his sight until we get there?”); and in a brief interview clip, she explains calmly that domestic violence should come as no surprise in a society that burned its women healers at the stake.

It’s easy to imagine how powerful these second-wave gems were to watch then, in the tumult of their time, because they feel risky even now, as hasty missives from a movement with no road map. As such, they offer us no instructions, but remind us that heroic acts of speaking out are always precipitated by speaking to one another, whether in private, in small groups, on Google spreadsheets, or through works of art.

Johanna Fateman is a writer and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She is coeditor of Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, forthcoming from Semiotext(e).