Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

The musician’s powerful new album defies categorization with its

subdued quietude.

New Blue Sun, by André 3000, Epic Records

• • •

André 3000’s new album, New Blue Sun, is the X in the road where several roads meet. This is the first instrumental release by a rapper who is without equal as a vocalist and admires the music of Alice and John Coltrane, but here has made something closer to the atmospheric sounds of Japanese electronic musicians from the ’80s and American New Age artists who released private-press cassettes in the ’70s. You do not need to care about any of that, though, because it’s not likely you’ll find New Blue Sun difficult. This music gently outlines the space it plays in, as much a vibrational frequency as a set of melodies and ideas. Leave it on loop, like an electric water-and-stone fountain bubbling away, and let its modest nature reveal its strengths.

Even if you have only paid glancing attention to rap in the last few decades, you know André Lauren Benjamin from Outkast, especially songs like “Hey Ya!” (mostly André’s work alone) and “The Way You Move” (mostly that of his partner, Big Boi). Within hip-hop, Outkast has its own significant lineage, largely of mastery and then apostasy, moving outside the bounds of familiar styles almost immediately after their 1994 debut, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik (which was heavily indebted to West Coast G-funk and The Pharcyde). In fact, André has stepped swiftly out of his last set of footprints every time he’s made an album. New Blue Sun bears little formal relationship to anything at all that he has done before—as the sticker on the vinyl version says, “WARNING: NO BARS.”

This is also André’s first album release in seventeen years, though he has shown up as a guest MC during that pause and has appeared in a few spots as a flutist (some of them uncredited). There are often pauses in the careers of radical artists, especially in Black American music. These silences need not be long to signify. Those suspensions remind the audience that the artist is not, despite the reference to chart hits I’ve just made, a commercial entity, like a bakery or a magazine. Artists have to make sure they are spiritually aligned before they proceed. Miles Davis took several years off after his streak of electric albums in the ’70s, and D’Angelo took fourteen years to complete Black Messiah, his third album. André’s pause was longer than either of those.

To unconfuse yourself, you could listen to New Blue Sun as if it were a Carlos Niño & Friends album, then listen to the actual CN&F albums, and then go back to NBS as if it were an André 3000 album. Your perception will change. I got to speak with André’s main coconspirator, Niño, on the phone this week, and he filled me in on some of the ways the album came to be. In January of 2020, the percussionist met André at an Erewhon in Venice, on the coast of California. Niño invited him to a show he was playing that evening, and the musician stayed all night. Niño provided a variety of percussive sounds and helped André assemble and refine what he has since called “spontaneous compositions.” Niño ran the studio sessions and invited all the musicians we hear. The core band included Nate Mercereau on guitars and guitar synths and keyboardist Surya Botofasina. The majority of this album consists of these four musicians responding to each other, and whatever editing and layering Niño and André may have done after the fact, New Blue Sun feels like live music, performed and heard in real time.

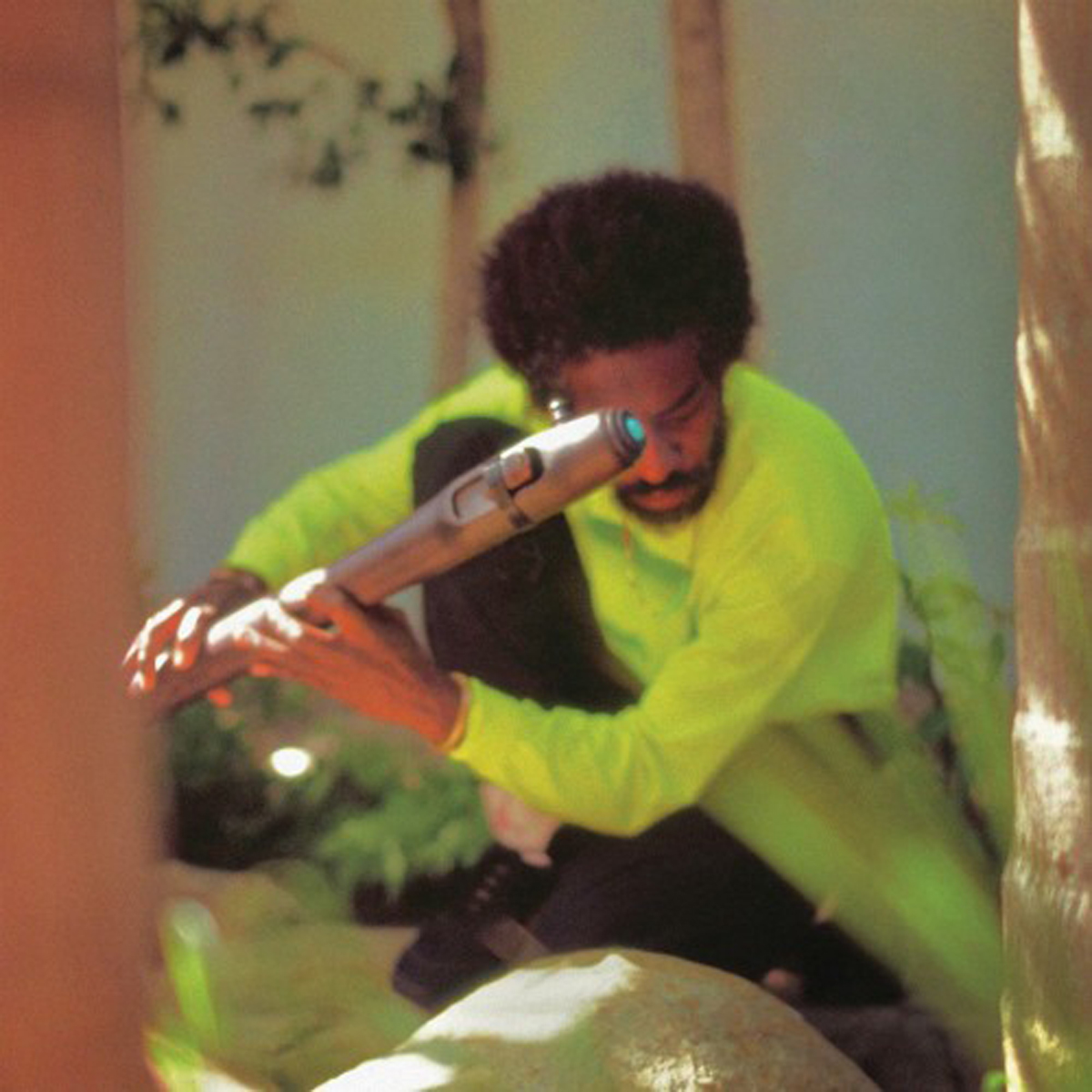

André took up the flute before the pandemic and started testing out various wind instruments while making The Love Below, before its release in 2003. In a recent interview with NPR’s Rodney Carmichael, he noted that the flute is “the first instrument where we actually heard a musical tone” and that “it’s the closest to the human voice out of all the instruments.” André has over thirty—his guess—wind instruments and has started working as an apprentice with Guillermo Martinez, who made the cedar Mayan flute that André plays on track three and holds on the front cover. He also told Carmichael that he admires Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders for their ability to “actually say something, or make me feel something, without saying something.” He called the larger body of jazz improvisation “sounds and tones that can be translated in any way,” which he finds “really attractive.”

I quote this at length because New Blue Sun is a serious work of instrumental music, even when it is casual and serene. The song titles are slightly overstuffed, perhaps because there are no other words on the album. “The Slang Word P(*)ssy Rolls Off the Tongue with Far Better Ease Than the Proper Word Vagina. Do You Agree?” is one. André described the titles as his attempt to “humanize it or punkatize or, like, make it less precious.” Having spent my adult life titling instrumental compositions, I understand the challenge. (His titles recall those by the American instrumental rock band Don Caballero, in particular, “In The Absence Of Strong Evidence To The Contrary, One May Step Out Of The Way Of The Charging Bull,” from their third album.)

Whatever you are expecting, this music is probably more subdued. There are long stretches of scene-setting—just slow keyboard figures and small bits of guitar, while cymbals lurk almost beyond the range of hearing and André sets out his themes and improvisations. (Sometimes, he plays digital flutes that don’t sound much like wind instruments but rather woozy keyboards.) Technically accurate description threatens to insult the music. The most notable sensation produced here is of patience, of people listening carefully to each other. After looping New Blue Sun for several days, I found most other music too acute or too immediately willing to reach conclusions. Adjust to its pace, and you will hear dozens of moments that turn brightness into sustained light, or that play with the shape of the listening frame.

Because André’s flute is almost always going through an effect of some kind—often the pedal board he helped design—it would be misleading to think of this as a “flute album.” Niño told me, “When people refer to New Blue Sun as a flute album, we laugh, because there are real flute albums out there. One of the greatest flute albums ever, also released by Epic Records, is Inside by Paul Horn, which came out in 1968. It’s an album that many people have in their collections and it’s literally just flute. There’s some chanting on it as well, but it is a flute album.” The guitars and keyboards and flutes on New Blue Sun all imitate each other—in fact, the very first notes on New Blue Sun are not played on keyboards, as I thought they were, but are Mercereau’s guitar synth forming chords.

Better, perhaps, to think of all the sounds on the album as harmonic spaces that contract and expand. This record is not something that should be filed under ambient or jazz or New Age, despite some affinities. If there were a genre called “quiet improvisation,” New Blue Sun might fit there, though one can assume André would be perfectly fine with it fitting in precisely nowhere.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, was just published by Semiotext(e).