Sowon Kwon

Sowon Kwon

Over eighty works on view at the Guggenheim present a grand narrative of ’60s and ’70s Korean avant-garde art.

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, installation view. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, center foreground: Jung Kangja, Kiss Me, 1967/2001.

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, cocurated by Kyung An and Kang Soojung, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum,

1071 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through January 7, 2024

• • •

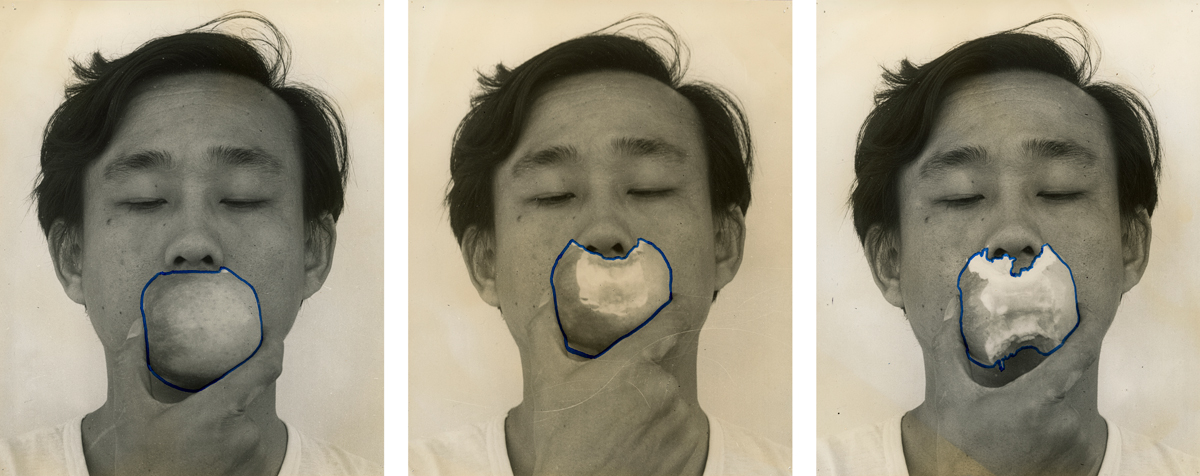

In the Guggenheim’s promotional materials for Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, two uncaptioned images are most prominent: Kiss Me (1967/2001), by Jung Kangja, a cubby structure with plastic sheets of “teeth” and found objects encased in outsize pink plaster lips; and Apple (1976), by Sung Neung Kyung, from a sequence of black-and-white photographs capturing him biting an apple with eyes closed. A pronounced orality figures in both: Could their selection signal the communication team’s desire, however unconscious, to drive home an association with a phase of psychological development even younger than the youth invoked in the title?

Sung Neung Kyung, Apple, 1976 (detail). Seventeen framed gelatin silver prints with marker pen, each 9 7/16 × 7 5/8 inches. Courtesy Daejeon Museum of Art. Photos: Jang Junho. © Sung Neung Kyung.

Some of the most engaging material in this show of eighty-plus works categorized as 실험미술, silheom misul—a term conferred in the early 2000s by art historian Gim Mi-gyeong—are the archived ephemera placed in vitrines and along a timeline. Except for the confusing inclusion of Kim Kulim’s 2021 drawing therein (a proposal for draping the Guggenheim’s facade with funerary fabric, as he did to Seoul’s National Museum of Modern Art in 1970), the artifacts add much welcome context. Photographs of “events” and “happenings,” as well as brochures, magazines, and press, give some sense of the lively, perhaps chaotic and competitive energy among this first generation of artists to come of age after the Korean War. The well-funded exhibition catalog, in both Korean and English volumes, is similarly informative.

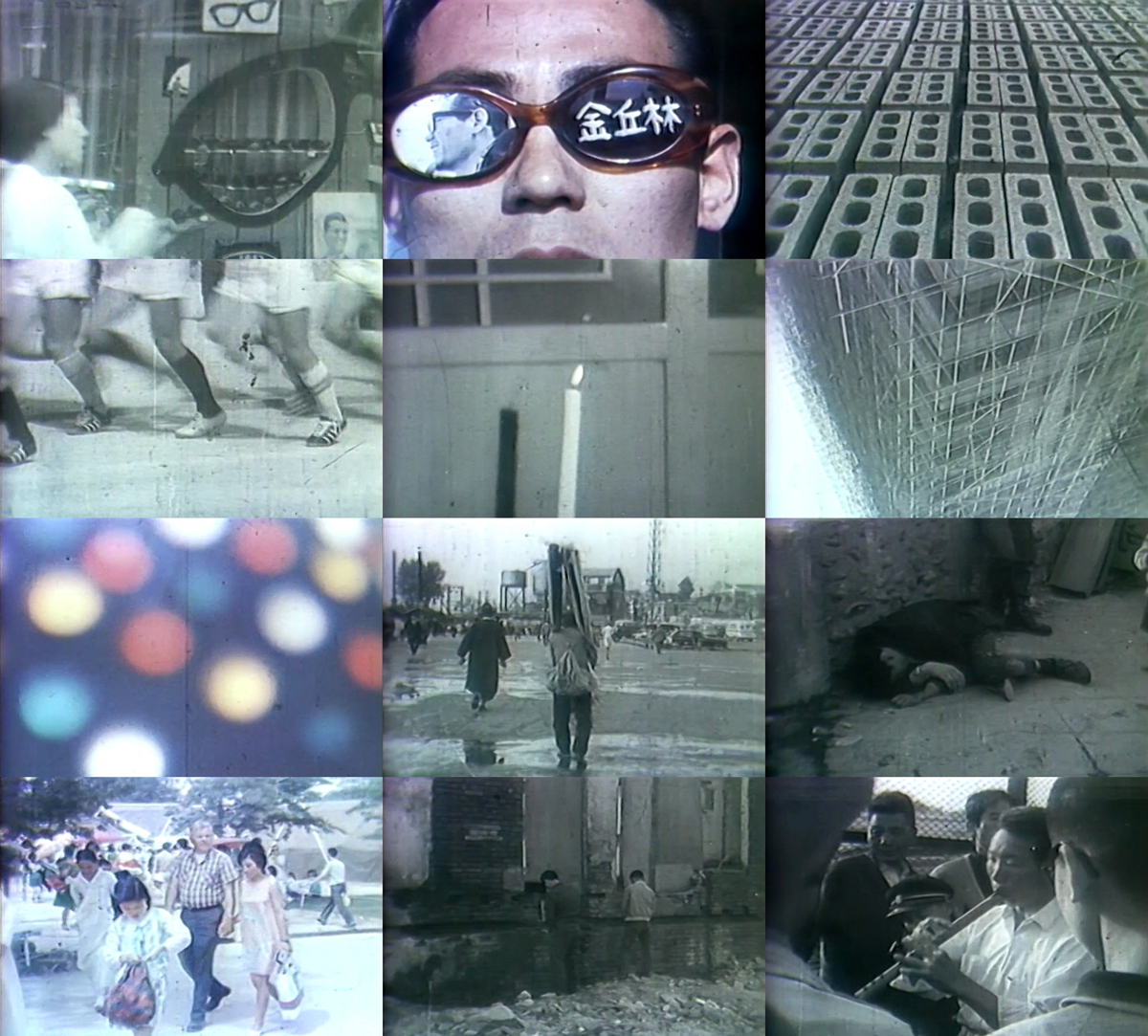

Kim Kulim, The Meaning of 1/24 Second, 1969 (still). Color 16mm film, silent, 9 minutes 14 seconds. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. © Kim Kulim.

“A New Beginning”—the thematic for floor two—has a Lucasfilm ring to it, but the installation itself feels more tasteful and studied than blockbuster. Jung’s sculpture, seen in person, has a low-wattage glow, suggestive of displays for cosmetics counters or even dental services, but also of a semi-theatrical staging of potential “props.” The mouth’s expression is both inviting and cryptic, like a mega emoji, possibly smiling, possibly gritting. Also on this floor is Kim’s experimental film The Meaning of 1/24 Second (1969), considered Korea’s first. A silent montage of urban scenes and a drowsy/anxious “protagonist” in fragmentary snippets, it cues Seoul’s pace of modernization as restless, even relentless. The number of groups and short-lived collectives, their members intermingling, is striking. In documentation, we glimpse their engagement with quotidian conditions and objects: smiling picketers at an opening, balloons attached to a seminude body, a funeral procession (Union Exhibition artists, Jung, the Fourth Group); or seated figures, quietly cross-legged outside a train station, or getting a haircut, or holding an umbrella to the tune of a folk song (group 19751225, Chung Chanseung and Lee Kun-Yong, Shinjeon and Zero [Mu] Groups).

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, installation view. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, center back wall: Lee Kun-Yong, Logic of Hand, 1975/2018.

Painting is well represented; many silheom misul artists were trained in “Western painting” and continued or returned to it in later years (Suh Seungwon, Choi Myoungyoung, Lee Hyangmi). Distinct from the dominant trend of Informel abstraction, works on the second floor also call up or incorporate industrial and everyday materials, such as vinyl and plastic, barbed wire and steel springs, metallic pipes, gas masks, and neon (Choi Boonghyun, Ha Chong-Hyun, Lee Taehyun, Kang Kukjin). In Moon Bokcheol’s Situation (1967–68), bisected gourds once ubiquitous in preindustrial Korean households are integral to the composition.

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, installation view. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured: Lee Seung-taek, Untitled (Sprout), 1963/2018.

Lee Seung-taek strives to locate universality in “Korean-ness” via folk traditions in his sculptural works using mulberry paper, earthenware, and ceramics, which have a big footprint on floor four, “The Logic of Resistance.” Lee Kun-Yong’s performance-based photographs and drawings consider the existential limits and freedoms of the body as a medium in simple, even mundane acts, such as moving in and out of a circle inscribed on the ground. Marker drawings on plywood from his The Method of Drawing series (1976–79) take up the central gallery space. The incongruity of the luxe Plexi and steel plinth construction “protecting” works made with such modest means was distracting. But as Lee and Sung Neung Kyung share a direct sunbae-hoobae (senior-junior) relationship as members of Space and Time (ST) Group, it feels right that Sung’s Newspapers: After 1st of June 1974 is installed just adjacent.

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, installation view. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, center, back left wall: Sung Neung Kyung, Newspapers: After 1st of June 1974, 1974.

Pages from the daily Dong-a ilbo are mounted on four panels, but with the articles cut out, leaving only captionless images and advertisements—a record of Sung’s performative action during a period of intense press censorship by President Park Chung Hee’s brutally authoritarian administration. Behind the open-worked sheets, now oxidized brown, are multiple crisscrossing scored lines, and one newspaper is dated 1978, suggesting Sung continued cutting for years thereafter. The wall label relates that, in December 1974, the Dong-a ilbo, in a provocative response to sponsors withdrawing under government coercion, printed the paper with all advertising spaces left blank—in effect, a reversal of Sung’s excisions. Art historian Joan Kee characterizes the publishing incident as “infamous,” perhaps because the immediate result was even more forceful and repressive consequences for frontline journalists.

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, installation view. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, left foreground: Lee Kun-Yong, Corporal Term, 1971/2023.

Floor five, “The Global Village,” has an international focus and reach, foregrounding artists who participated in biennials in Paris and São Paulo as well as exhibitions in Seoul and Daegu. The “non-site” presence of Lee’s now-iconic Corporal Term (1971/2023), a tree chopped at mid-trunk with its roots still embedded in a cube of soil, keeps company with Park Hyunki’s Untitled (TV Stone Tower) (1982). A photographic slideshow documents Lee Kang-So’s Disappearance—Bar in the Gallery (1973), in which he relocated the furniture from a working-class bar into a commercial gallery; I recognized an Oran-C, a throwback soda drink. The bottle reminded me that in Lee Hyeonjae’s 1978 untitled color video downstairs, a figure pours and repours Coca-Cola into glasses, then back into the bottle, to the point of spillage and overflow.

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, installation view. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, far left: Park Hyunki, Untitled (TV Stone Tower), 1982.

The great range of practices was incredibly heartening to see, and yet I was left with the overall impression of a pervasive, almost sanitized elegance. In the assertion of a “movement” called Experimental Art, just now being consolidated (in the guise of being retrieved) as the Korean “avant-garde,” to what extent are artworks to function as ambience, and/or just so much evidentiary fodder? I have come to understand this exhibition as being as much, if not more, about art history and the discipline’s propensity for constructing neat canonizing narratives as about prioritizing artistic choices and material exploration pursued by makers.

Lee Kang-So, Disappearance—Bar in the Gallery, 1973 (detail). Ten digital chromogenic prints, each 31 × 42 13/16 inches. Courtesy National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. © Lee Kang-So.

Art and scholarship serving institutional and market legibility is hardly news. And when Guggenheim director Richard Armstrong underscores the museum’s “commitment to offering new perspectives on existing narratives,” now with Korean exemplars in tow—artists of “vanguardist brio,” as he puts it in the catalog—he is certainly on brand. But this old story of “new” discovery, of looking elsewhere to feed an entrenched grand narrative of (Western) avant-gardism, reaffirms a discourse in which colonialism and primitivism have been structural. In showcasing “avant-garde art,” which is generally marked and historically borne out by transgressive, disruptive practices often pointedly outside the market, the museum traffics an ethos that bristles against one status quo to uphold another. That artists are willing participants is arguably less evidence of the power of that narrative than a calculus of professional survival and informed risk.

All the avant talk put me in mind of the less glamorous arrière. To engage the military metaphor is also to speculate on an interdependence between the two. Idiomatically, rearguard actions are preventive attempts to defend from behind, though it is likely too late. If in tandem you also consider art’s capacity, when not lost to obscurity (whose obscurity, another sunbae asks), to bridge different temporalities, other propositions become highly suggestive. For example, it can posit the possibility of imagining not only newspapers of record but also big museums without ads, without sponsorships. For at least a few infamous days.

Sowon Kwon is an artist and educator based in New York City. She is working on a series of text-based animations that explore coincidence, polyvocality, and Cold War subjectivities.