Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

A twentieth-anniversary reissue of The Greatest renews faith in the artist’s soul-baring songs.

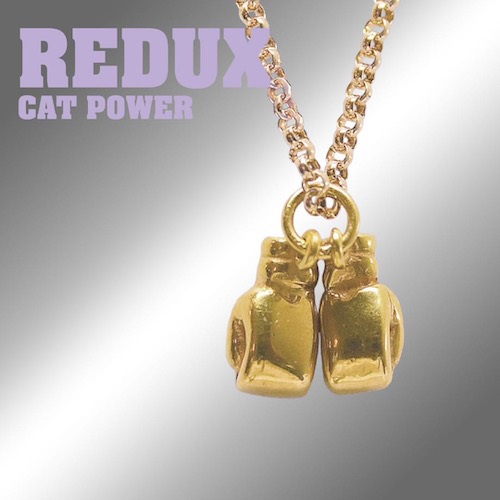

The Greatest and Redux, by Cat Power,

Domino Recording Company

• • •

God is resident within each and every one of us to an equal degree and music is one of the few reliable ways we have of expressing—or measuring—this fact. We can see how this relates to the expanded version of Cat Power’s 2006 album, The Greatest, by listening to Ian MacKaye. (The Greatest is being reissued twenty years almost to the day of its initial release, appended by a new three-song EP of previously unreleased covers, called Redux.) The punchline, before the routine, is this: punk rock was like the folk revival before it and half a dozen rap beefs after it—an attempt to return the divine to its appropriate human form, away from deceit and mammon and feckless inflation.

In May of 2015, Daniel Dylan Wray interviewed MacKaye for Loud and Quiet. MacKaye, the founder of Fugazi and Minor Threat, as well as the Dischord label, made three points about his work as someone in the loosely defined cohort of punk. “Music for me is sacred; it’s bigger than [drinking and doing drugs],” to which he added, as a contrast: “For me punk was construction, I’m a construction worker.” Rounding it out, he said that “what I loved about punk rock was that the audience was just there, almost by default—there was no profit; profit wasn’t part of the equation.” The relationship of the sacred to the daily cycle of the construction worker seems obvious enough. It’s not advisable to go to work every day fucked up on drugs if you’re laying the foundation for, say, a church. That’s what MacKaye, Matador Records, and Chan Marshall (who would become Cat Power) have been building.

The label that first put out The Greatest is rooted in the soil of punk rock. Matador co-owner Gerard Cosloy ran Homestead in the ’80s, which captured the explosion of American bands in the minutes after punk imploded, and Matador continued in that loose family of impulses. The UK-based Domino, with whom Marshall signed in 2018 and who is issuing Redux, started out licensing American labels like Drag City that followed a similar path of Children of Punk Who No Longer Make Punk. Which brings us to Cat Power, Marshall’s solo act that began life in the ’90s with shows so prone to collapse that it was hard to watch her. Some, more than a few, ended with her simply leaving the stage after fifteen minutes or so.

And that was typical of the ’90s iteration of what was no longer punk but of punk, an independent strain that saw its apotheosis in Kurt Cobain. Marshall’s fragile side, originally an impediment to performance, was simply folded into the work, enabling her to convey the unbearable while staying in the room with us. It was impossible to hear her and not be aware that the sacred was afoot. This led to things in the indie world that might be called hits if they were measuring sales: the 1998 song, “Cross Bones Style,” ended up playing through the finale of the cheeseball new Sarah Snook vehicle, All Her Fault.

Gregg Foreman, Judah Bauer, Jim White, Stuart Sikes, Eric Paparozzi, and Chan Marshall (foreground). Courtesy Cat Power.

The Greatest represents one of many endings for the idea of punk rock, the endless dialectical burps wherein the negator becomes the headliner. The labels and musicians that brought Marshall out into the light would never have been possible without punk rock, yet here was a woman singing in the most classic soul tradition, and with an actual lineup from that era including guitarist Teenie Hodges and other members of the Hi Rhythm Section that backed Al Green. The soul in soul, it turned out, was no different from the soul of punk rock.

This was a coup of both singing and writing, as all thirteen of the album’s songs are Marshall originals. (The Redux EP contains covers of James Brown’s “Try Me” and Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U,” as well as a reworking of “Could We” from The Greatest.) The title track was something of a shock in the moment of 2006, when indie acts and labels were still tied to bits of refusenik DNA from punk: ineptitude, distortion, mulish embraces of the pitchless. Not here. “The Greatest” gives us a world-class rhythm section moving slowly but without mourning, with actual strings to sweeten the actual deal. Marshall sings with several timbres at once, like the greats, able to go from breathy to tobacco-scratchy to high and pure while sounding like everything is of the greatest emotional import. Her writing here is legendary, pitting her deep vulnerability against the idea of Muhammad Ali: “Once I wanted to be the greatest / Two fists of solid rock / With brains that could explain / Any feeling.” We are in a Memphis soul record with a more unpredictable singer, and yet it’s a voice with all the tonal breadth and emotional weight of the soul singers you already know.

But Marshall’s lyric keeps her dark-and-light combination pleasantly upside down: possibly even punk, who can say. “Love & Communication” does not have the Memphis-soul feel entirely—it’s too slow and fuzzy. Against this, Marshall is easy, not too dramatic, more in her fighter stance hopping around and changing her vocal inclinations. The scene? Weirder than you’d expect: “Love and communication / You were here for me at this very moment / ’Cause I found you on the phone / You called me and you were not hunting me.” Come along for the ride, she says, “you just know you should.” So maybe she’s doing the hunting?

Twenty years later, it seems as if she found the spiritual links between American soul and its intractable punk nieces, that rough devotional urge. The new covers are of a piece with her other work over the last five years, like a live version of Frank Ocean’s “Bad Religion” for James Corden, or the entirety of Dylan’s Live at Royal Albert Hall performed and recorded at the Royal Albert Hall. Which is to say, she maps the contours of the song she needs, not what you need. Your favorite fillip may not make the cut, and with Prince, she jettisons most of the melody that makes the song succeed for many. She actually inverts the emotional architecture of the song, dissolving the builds and using a hole-puncher at the pitches, taking out all the high notes you try at karaoke. She is daring you to have faith in her faith—this is exactly the opposite of karaoke, or any kind of obvious bid for applause that would ruin the sacred at the heart of this, or any other, song. She is hearing what we can’t and this is why we return to her church again and again.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, was published by Semiotext(e) in 2023.