Rachel Haidu

Rachel Haidu

With wit and sly subversion, Ulrike Müller revisits—and revivifies—the legacy of modernist painting at Callicoon Fine Arts.

Installation view, Ulrike Müller, And Then Some, Callicoon Fine Arts, 2016. Image courtesy the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts. Photo: Chris Austin.

Ulrike Müller, And Then Some, Callicoon Fine Arts, 49 Delancey Street, New York City, through October 30

• • •

Since modernist abstraction’s arrival on the scene in the first decades of the last century, and especially since abstract painting acquired hegemonic status in New York in the midcentury, it has been considered démodé and even regressive among certain circles to allow one’s eyes to search out the figure. For good reason: abstract art demands that we see it as itself, not referring to any thing or person in the world. But at various points in the last century, figuration, along with ornament, wit, and even language, have infiltrated the lexicon of abstraction, not “ending” it by any means but tampering with its ultimatum-like finality.

It’s into that very historical fray that Ulrike Müller’s latest exhibition, And Then Some, at Callicoon Fine Arts, enters. Müller’s work addresses that painterly modernism which rested on abstraction as if it were a hygienic sanitization process, cleaning the medium up of not only its associative or “illusionist” capacities but its anthropomorphism, charm, and sexiness. The result is a show that aims forthrightly to delight us with its lively wit, and, more surreptitiously, to allow a thorough rethinking of modernism and its alleged, programmatic assumptions.

At Callicoon, Müller’s paintings are as dexterous as they have ever been. Most in the show are on paper; a few are enamel, and even fewer are on canvas. They remind us of vases, faces, flirtations. Her earlier paintings on vitreous enamel on steel—a medium she has made her own for the past decade—made ambiguous associations to sexed or unsexed body parts (is that V-shape a knee, is that hump a haunch?). Over time, and thanks in part to a new color palette, these enamel paintings have begun to look more “abstract,” like the kinds of line-and-color experiments that populated communally oriented modernist workshops such as the Bauhaus and the Wiener Werkstätte. But a more striking departure from her earlier work is to be found in the more figurative drawings in acrylic paint and papier collé on paper. There, we confront a figure on a ground, expressed always in the uninterrupted line of paint, its viscous, mono-colored brush-drag virtuosically clean. But this virtuosity is friendly, wants you to come inside; it is not a mere display.

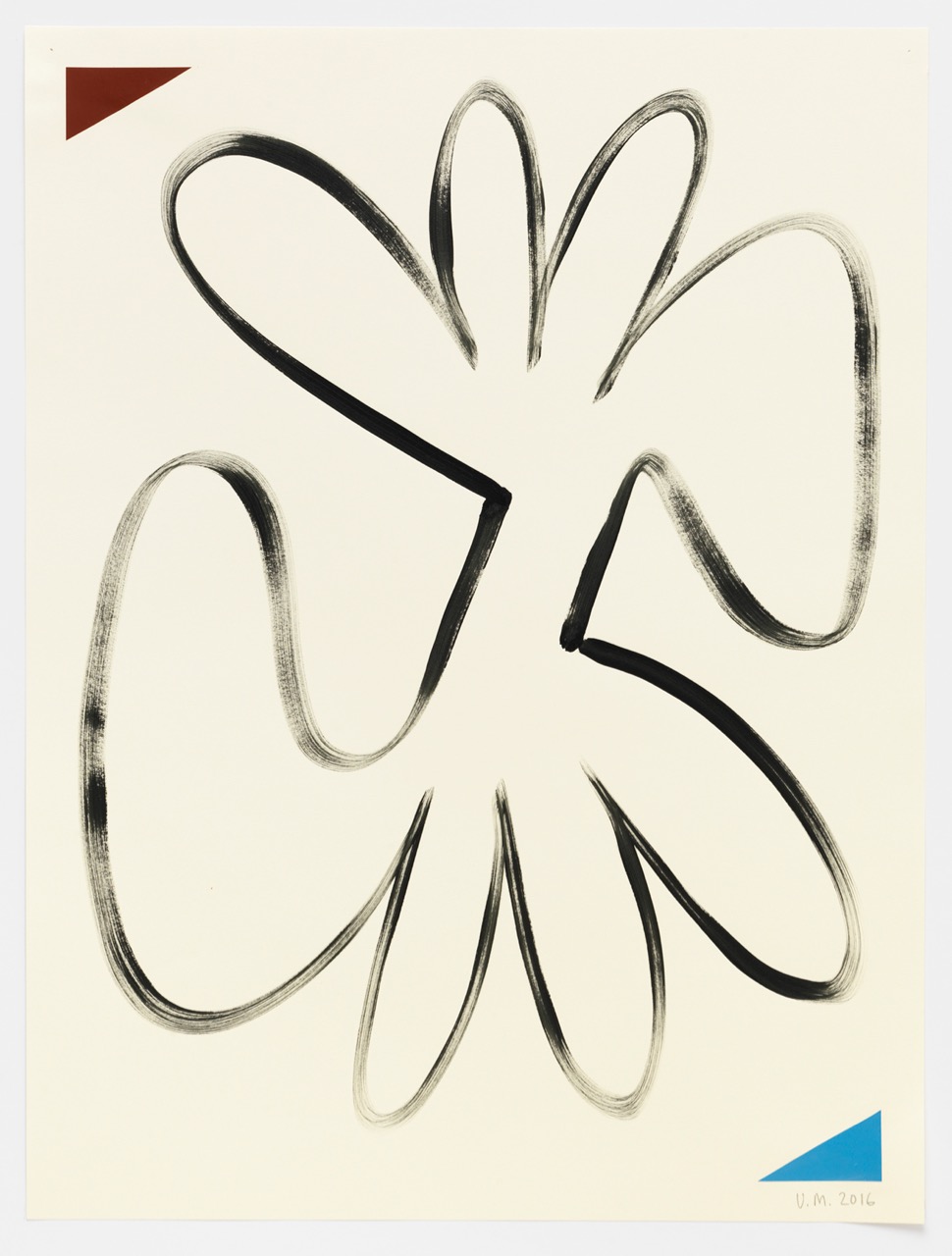

Ulrike Müller, Brat, 2016. Acrylic and papier collé on paper, 23 1/4 × 18 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts. Photo: Matt Grub.

In Brat (2016), the hyper, eight-legged or -petaled shape moves just like a “brat,” with a mind of its own, not tethered to the polite corners, one marked in blue and one in dark red. Other works in acrylic and papier collé on paper, like Façade and The Smoker (both 2016), are faces and architecture. They remind us of the stylized, metonymic manner in which a face could be signaled in abstraction’s early days, or a right angle made more impressive, more meaningful, in a building. And, like those early, communally oriented avant-gardes, they too tread that line between the modular and the ornamented, the systematic and the individual.

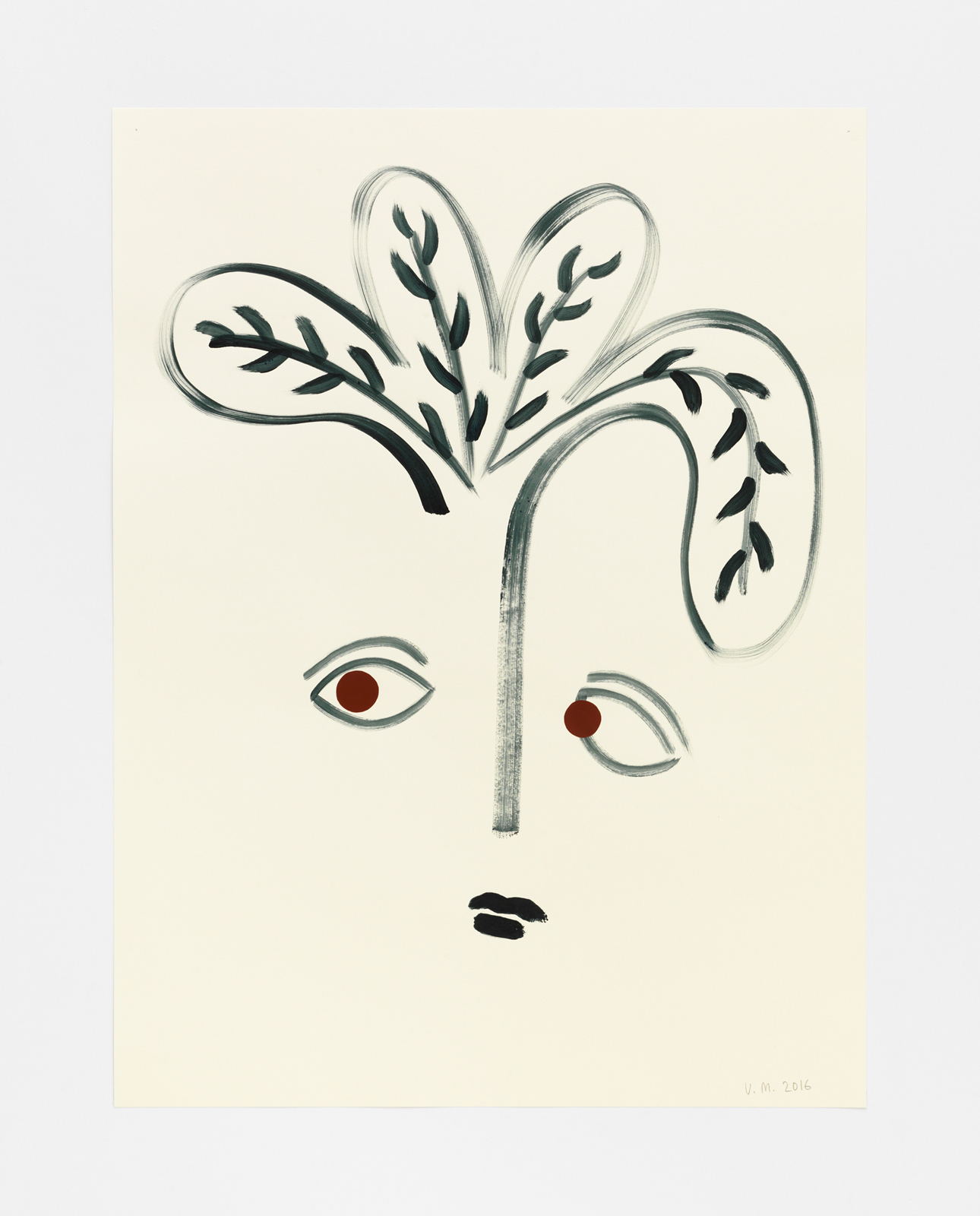

Ulrike Müller, The Smoker, 2016. Acrylic and papier collé on paper, 23 1/4 × 18 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts. Photo: Chris Austin.

Müller’s work both turns subtlety into an issue and dispenses with it: her game does not involve making life difficult for the viewer, but rather in asking us to examine what we want from subtlety, from nuance, from undecidability. One of the signal themes of the show is the bouquet, and indeed it was an earlier enamel painting of a vase topped by three balls—blossoms in black, red, and light green, signified simply by circles—that seems to have tipped her trajectory from a confrontation between abstraction and figuration into something more complicated. In her enamel paintings, at play is the magnetism, the dynamic between this-and-that. We see it through the vertical bisection of many of the enamel rectangles: this play of a curve that could be a breast except that then, two paintings away, it rotates into a diagonally tilted, curve-edged rectangle. When she moves onto paper, the modality is no longer a set of mechanisms: of tilt, fold-and-double, slot-in-different-colors. Instead it is a question of where that “ambiguity” leads us; what kinds of anxieties are produced by a “figurative” reading, by seeing a face or a bouquet? In the painting on paper Bouquet des Fleurs, the figure is explicitly coy or charming, its worried eyes glancing sideways as a bouquet of leaves grows from its nose, and we are reminded of where modernism was when it shunted expressivity for purer forms.

Ulrike Müller, Bouquet des Fleurs, 2016. Acrylic and papier collé on paper, 23 1/4 × 18 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts. Photo: Chris Austin.

Modernist painting arguably reached its first apogee when European painters were confronting the outbreak of what would, in 1914, be the most catastrophic global war yet. Not only through Bouquet’s worried expression, but through their oddly acute and yet generalized sense of the presence of history do Müller’s paintings evoke those moments when European bourgeois culture authorized its self-destruction, and plenty more.

Those moments—replete with epic grandiosity and haunting loss—have “always been with us”—a phrase I borrow and deform from the title of Müller’s recent exhibition at Vienna’s Museum Moderner Kunst, The old expressions are with us always and there are always others. It was shown alongside the new presentation of the MUMOK’s holdings, which Müller co-curated with curator Manuela Ammer, titled Always, Always, Others: Non-Classical Forays into Modernism. Folklore, animals, crafts, and bodies, in the works of many long-unseen painters from the depths of the museum’s collection, infused a new sense of what “modernism” could hold, shaking the European canon loose from its teleologies. Klee’s semiotic tapestries, Miró’s flat, curvy planes, Picasso’s urbane still lifes, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s geometric compositions—all of these ghosts can be found in Müller’s painting. But so can the spirit of craft and social-therapeutic art workshops, of those self-taught artists whose modernisms are no less stunning for being shut out of art history, and yet no less historical. Indeed, the “us” is ultimately what is at stake in Müller’s work, just as it is, for some, the stakes of modern art itself. By drawing us back toward those “others”—other modernisms, more communal and agitated, less cautious, more open—Müller enables a rereading of what modernism and indeed painting has done or could do.

Rachel Haidu is an associate professor in the Department of Art and Art History and director of the Graduate Program in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester. She is the author of The Absence of Work: Marcel Broodthaers 1964–1976 (MIT Press/October Books, 2010) and numerous essays, most recently on the works of Ulrike Müller, Andrzej Wróblewski, Yvonne Rainer, Sharon Hayes, James Coleman, Gerhard Richter, and Sol LeWitt. Her current book manuscript examines notions of selfhood that develop in contemporary artists’ films and video, dance, and painting.