Ed Halter

Ed Halter

From Joseph McCarthy to the Weather Underground: revisiting the films of the oppositional documentary maker.

Emile de Antonio, Millhouse: A White Comedy.

“Emile de Antonio,” Metrograph, 7 Ludlow Street, New York City, through May 7, 2018

• • •

Filmmaker Emile de Antonio was among the most prominent voices of the twentieth-century American counterculture, though his name has today fallen into relative obscurity. He chronicled his own era by examining topics of mythic potency; in just over a decade, de Antonio directed a succession of agitative feature-length documentaries on Joseph McCarthy (Point of Order!, 1964), the Kennedy assassination (Rush to Judgment, 1967), the war in Vietnam (In the Year of the Pig, 1968), the presidency of Richard Nixon (Millhouse: A White Comedy, 1971), the rise of American painting from abex to pop (Painters Painting, 1973), and the guerrilla activities of the Weather Underground (Underground, 1976). Produced in a range of nonfiction approaches, these works are unashamedly oppositional, formally inventive, and stubbornly class-conscious. Most enjoyed theatrical releases in their day, prompting acclaim from the left and consternation from the right. This week, Metrograph’s de Antonio series allows audiences a chance to see all the aforementioned titles and more, which in their collective picture reveal how our supposedly unprecedented moment has grown out of a long history of brute domination in American politics.

Beyond his own directorial output, “De” (as he was known to friends) helped jumpstart American independent filmmaking as one of the founding members of the New American Cinema Group in the early 1960s, alongside Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke, and others. He was also a prominent mover in the burgeoning art world, a member of circles that included John Cage, Frank Stella, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol; exposure to their methods, he claimed, would shape his approach to filmmaking. De Antonio’s encounters with Cage, for example, inspired his first film, Point of Order!, a cunning found-footage recitation of the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings.

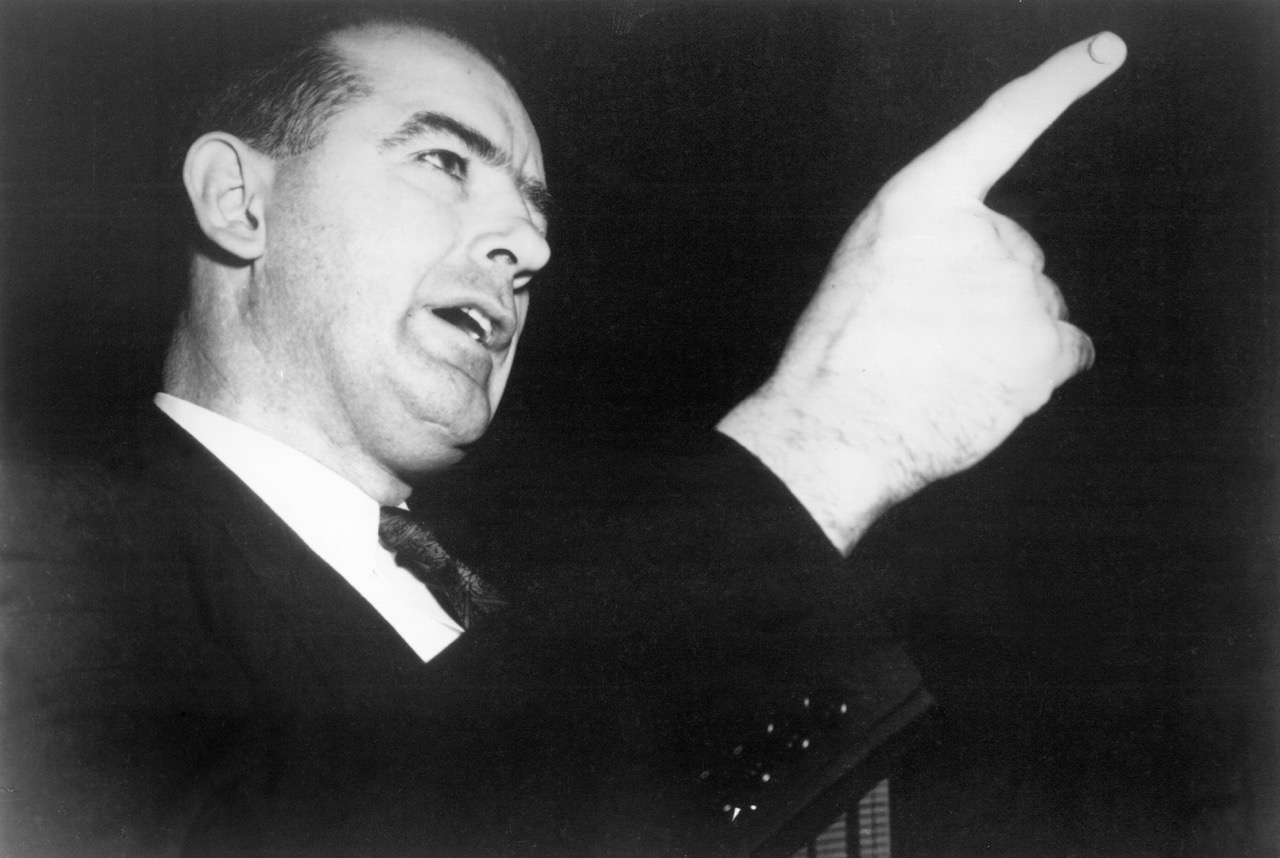

Emile de Antonio, Point of Order!

Produced with the help of distributor Dan Talbot, Point of Order! was edited from 188 hours of ghostly kinescopes of the hearings’ live television coverage, arranged into ninety-seven minutes that retell the events sans voiceover and with minimal titles. It was first released when the drama of the McCarthy era would have been remembered by the film’s viewers; in 2018, audiences might find themselves twitching to access Wikipedia on their phones in order to follow along. What remains is a study of political theater, with sharp portraits of a hectoring McCarthy and his fresh-faced legal weasel, Roy Cohn, surrounded by a larger panoply of slick-haired, fat-headed white men thundering quasi-preacherly oratory through the Senate’s chambers. Point of Order! now works not only as a reminder of how the Big Lie has functioned before in American politics, but also as a fascinating archive of mid-century elocution, a collection of pseudo-populist regional accents composed into an operetta concrète.

The collage technique used for Point of Order! renewed the power of the compilation film, a genre that had been used to poetic effect by earlier directors like Esfir Shub and Nicole Védrès, though more often employed by media producers as a cheap means to rehash old materials. Yet one of de Antonio’s hallmarks is his lack of formal dogmatism—notable at a time when the pieties of direct cinema held sway over documentary—and thus his later projects partially reject Point of Order!’s you-are-there immediacy. In Rush to Judgment, he mixes archival footage with original interviews and a lawyerly narrator in order to poke holes in the findings of the Warren Commission; although de Antonio’s film is a cool-headed attempt to undermine the official record rather than introduce an alternative explanation, Rush to Judgment nonetheless proved to be the granddaddy of the paranoid-critical conspiracy-theory documentary, for better or worse.

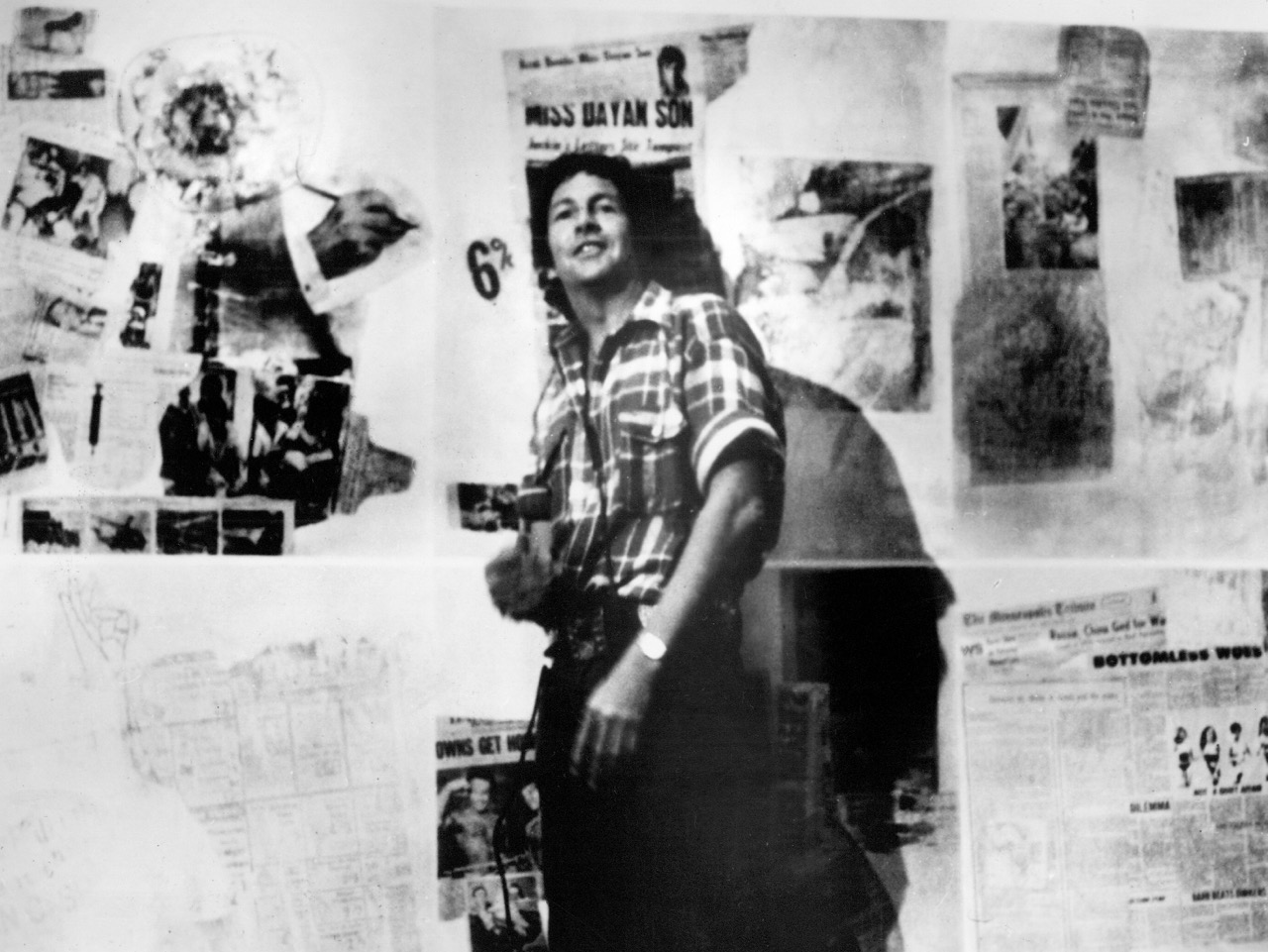

Emile de Antonio, In the Year of the Pig.

Though these early works remain fascinating artifacts, de Antonio only fully realizes the force-potential of his magpie aesthetic with In the Year of the Pig. The film answers the contemporaneous question of “Why are we in Vietnam?” with an essayistic montage of news footage, original interviews, and archival images that tell the story of America’s racist meddling in southeast Asia’s governance since the 1930s. The film’s opening sequence includes eye-slapping shots of a Buddhist self-immolation, set to an oscillating drone; the assault continues later on a more rhetorical level, when a tuxedoed American politician tells a reporter that the Viet Cong “are willing to die readily, as all Orientals are. Their leaders will sacrifice them, and we won’t sacrifice ours.” Like Point of Order!, In the Year of the Pig means to rebut television, but in this case its critique is additive rather than subtractive. “Every day we saw dead Americans, dead Vietnamese, bombings,” de Antonio later told an interviewer, but “never one program on the history of it; never one program attempting to place it in context.”

Emile de Antonio, Painters Painting.

Among de Antonio’s most personal works, Painters Painting mines his own relationships with Rauschenberg, de Kooning, Warhol, and numerous other men (plus Helen Frankenthaler, the lone woman artist featured), interspersing generous 16mm black-and-white interviews with motile 35mm color shots of their canvases, recorded at Henry Geldzahler’s pivotal Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition, New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970. Though the film opens with a statement that American painting had long been “entangled in the contradictions of America itself,” Painters Painting largely avoids any direct engagement with politics, grappling primarily with aesthetic debates. Both the depth of its access and its insistence on understanding artmaking not merely as a craft but as a deeply intellectualized process make the piece a high-water mark for the possibilities of the art documentary, rarely equaled to this day. It can also be understood as an echo of de Antonio’s own directorial aspirations, expressed through critic Clement Greenberg’s remark that avant-garde art must have “shocks and surprises and puzzlement built into it.”

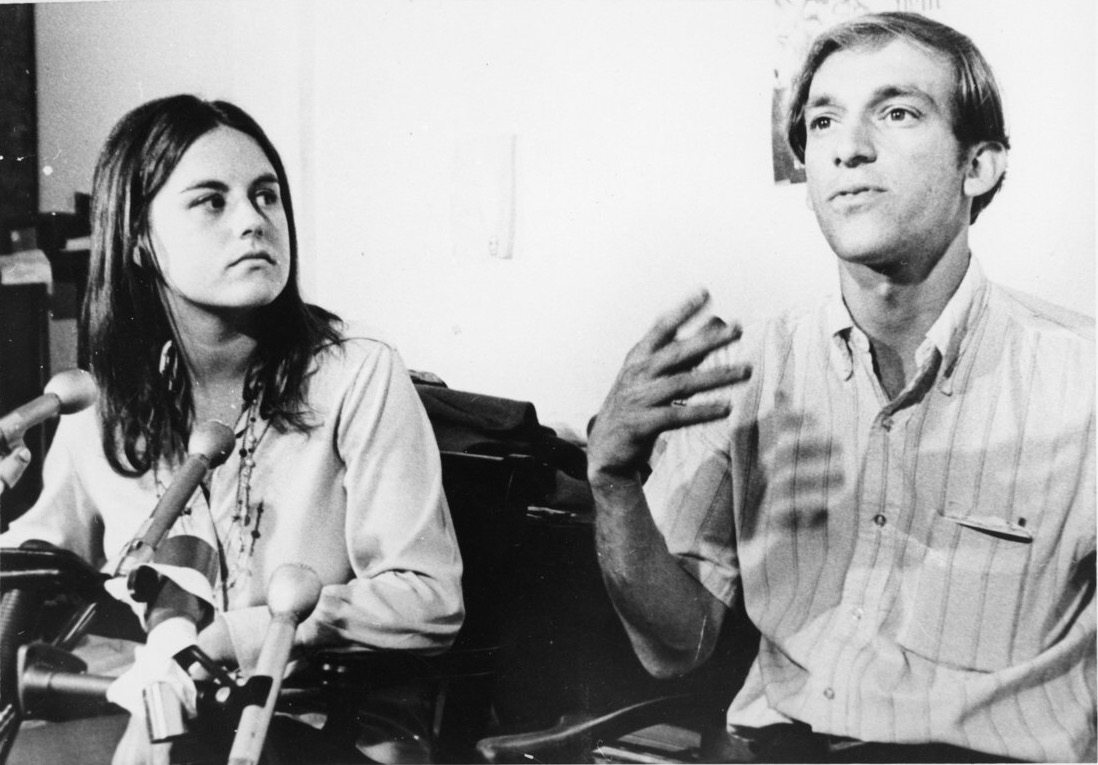

Emile de Antonio, Underground.

For Painters Painting, de Antonio includes shots of himself and his minimal crew, and this self-reflectiveness is expanded for Underground. De and his collaborators, Mary Lampson and Haskell Wexler, are at points depicted interviewing members of the infamous Weather Underground group by shooting into a wall-size mirror, granting clear views of the documentarians while recording their subjects from behind, anonymously. A subversive film in the bluntest sense of the word, Underground allows the criminalized radicals to speak for themselves, illustrating their arguments and recollections with images from the recent past. One interviewer from In the Year of the Pig states that the Vietnamese, unable to effect change through electoral means, were forced “to go underground and to understand politics only as revolutionary struggle.” Underground makes much the same argument for its American insurgents—a good reminder of the range of options available as we move forward.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was recently published by Seven Stories Press.