James Hannaham

James Hannaham

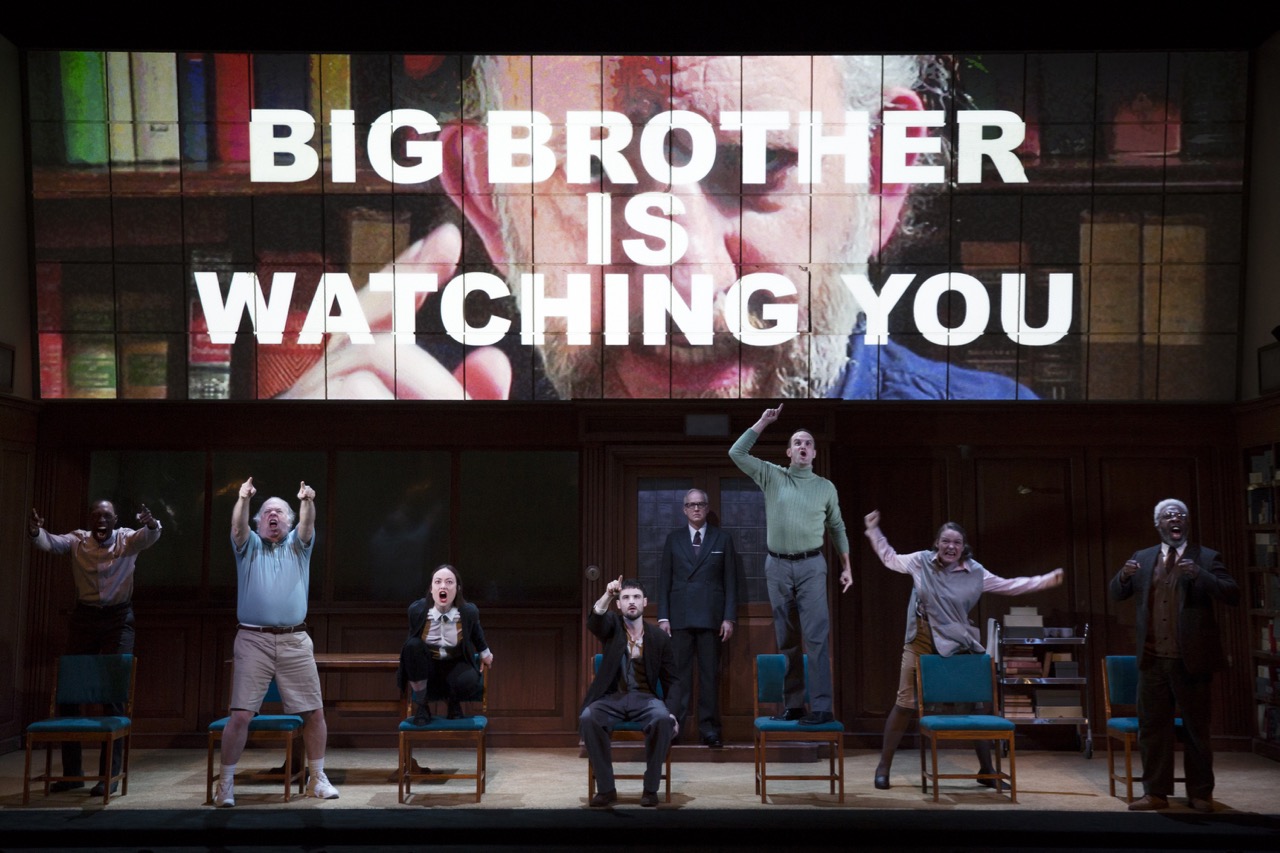

Big Brother gives his regards to Broadway.

The cast of 1984. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

1984, by George Orwell, adapted by Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan, Hudson Theatre, 141 West Forty-Fourth Street, New York City

• • •

Directors Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan have brought their disquieting adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984 to Broadway. One can be shocked by its presence there, feel the timeliness of Orwell’s warnings, and perhaps express awe at the play’s merciless depiction of brutality. But the show is mostly hard to like.

Then again, the novel, whose text makes up most of what gets spoken onstage, did not much want to be liked in the first place. Orwell meant his cautionary tale to scare the bejesus out of the Western world with its deeply pessimistic view of a totalitarian future. Which it did, very effectively—we call the components of any good dystopia “Orwellian,” we often speak of “thought police” and “doublethink,” we invoke 1984 any time we hear the term “surveillance state”—we even watch Big Brother, not vice versa. Over the years, multiple adaptations of the book have continued to stir up audiences, especially at moments such as our current one, when totalitarianism seems ascendant and politicians blatantly mangle the facts in public.

For those unfamiliar with the basics of 1984—Alpha Centurians?—the story concerns a man named Winston, who, trapped in an extremely repressive government, works for their Ministry of Truth—the propaganda department of the Party—and finds himself having strange (i.e., romantic) feelings for a coworker named Julia, who may or may not be working for the Thought Police. We learn a great deal about the society they live in and its strange rituals—for example, the Two Minutes Hate during which all good citizens momentarily call for the murder of Emmanuel Goldstein, the Trotsky-ish leader of their ideological opponents, known as the Brotherhood. Winston and Julia begin a forbidden relationship, as the state bans love of anyone except their possibly nonexistent leader, Big Brother. Things do not go well for them, to say the least. They’re discovered and separated (the question of whether or not Julia was working for the Thought Police remains open), and Winston receives one of the most infamous physical and psychological torture sessions in Western literature this side of de Sade. It’s a vicious indoctrination, not an interrogation—the Party’s aim is not just to gain a confession, but to break Winston down and make him love Big Brother. Their brutality culminates in a visit to Room 101, the place where the Party forces you to face your worst fear (perhaps their only nod to individualism). In Winston’s case, rats. And in this case, at least, torture works.

The cast of 1984. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

This particular adaptation of 1984 has none of the solemn majesty of Michael Radford’s 1984 film, certainly not the wild inventiveness and mordant humor of Terry Gilliam’s loose reworking, Brazil (1985). Perhaps a little unfair to compare stage with film, but in the case of such a well-known, frequently revisited story, the pressure to innovate could hardly get higher. The directors, however, do not yield to that pressure one iota. Icke and Macmillan relish exactly the experimental theater clichés of disorientation you’d expect—darkness, flashing strobes and loud bangs, subwoofers that growl through your intestines, a large video screen upon which offstage actors frequently do entire scenes. They’ve also rearranged Orwell’s chapters, and added a superfluous frame story (concerning a book club in the 2020s that is reading 1984) designed to soften the novel’s intentionally harsh conclusion. The rather charisma-less Tom Sturridge and Olivia Wilde, as Winston and Julia, do succeed at demonstrating to us how people who’ve never even heard of love might fall into it—haltingly, stupidly, pathetically, often while bent over awkwardly. But no one seems to trust Orwell’s ideas to be the scariest thing in the room.

Reed Birney, Olivia Wilde, and Tom Sturridge in 1984. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

In the show’s final twenty minutes, though—just before the big torture scene—it wakes up like Godzilla emerging from the Pacific. The militarized police raid on Winston and Julia’s secret hideaway creates an excuse for a gorgeous, scary, high-tech set change (kudos to designer Chloe Lamford). Stormtroopers pile onstage, semiautomatic weapons drawn; the panicked lovers shriek; scrims and huge walls light up, slide past, and disappear. It’s the kind of vigorous switchover that makes you wish the directors had infused the rest of the proceedings with the same dramatic energy and force. The show doesn’t get any better conceptually, but the pace gets faster, and it begins to tell the story through images instead of mangling Orwell’s text. Finally, the bright white walls of an empty Club Monaco—I mean, the Ministry of Love—descend, and we settle in for a remarkably unflinching—though still highly theatricalized—depiction of torture. Drenched in stage blood, Sturridge’s performance becomes several times more convincing. Ditto Reed Birney as O’Brien, Winston’s superior at the Ministry of Truth, who has double-crossed him and now reveals himself to be Winston’s tormentor. Birney’s calm, affectless reading of his lines contrasts chillingly with Sturridge’s impassioned pleadings for his life, his lover, and his sanity as his teeth are ripped out.

Tom Sturridge and Reed Birney in 1984. Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

Oklahoma it ain’t. This theater of cruelty spectacle doesn’t seem like what Broadway audiences usually want to shell out $150 a seat for, but I’m glad to see it there. It may not be likable, but perhaps it will help a few American theatergoers who otherwise remain at a distance from torture to experience, by proxy, the sort of “enhanced interrogations” that have been going on regularly in their name around the globe. The production’s extreme depiction of violence, live and in real time, might help vaccinate them against belief in such methods. Several media outlets have claimed that audience members have been fainting, vomiting, and fighting one another during this part of the play. Nowadays, that sounds like the beginning of a potentially fruitful political debate.

James Hannaham has published a pair of novels: Delicious Foods, a PEN/Faulkner Award winner and New York Times Notable Book, and God Says No, a Lambda Book Award finalist. He practices many other types of writing, art, and performance, and teaches a few of them at the Pratt Institute.