Tobi Haslett

Tobi Haslett

In his new poetry collection, Wayne Koestenbaum animates the everyday with the forces of theory, stylized futility, and an aestheticist’s will.

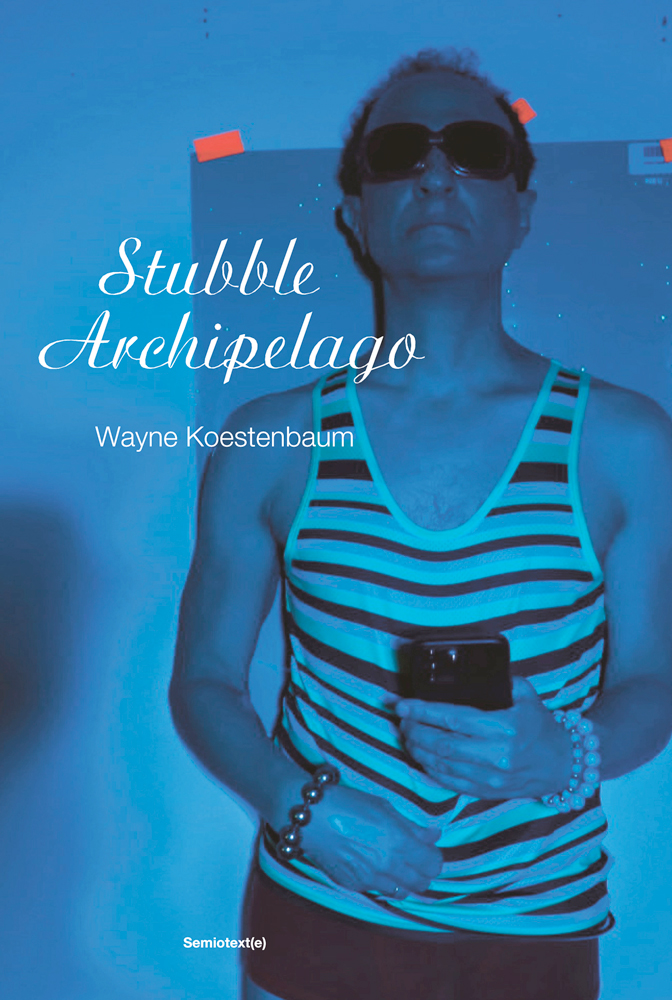

Stubble Archipelago, by Wayne Koestenbaum,

Semiotext(e), 100 pages, $15.95

• • •

The writer Wayne Koestenbaum has an essay called “Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sentences.” Allow me to say something about Wayne Koestenbaum’s own sentences, beginning with the following three, about the porn actor Ben Dodge:

I have grown to feel friendly and loyal toward him; I feel kindly toward him because he has given me a pleasure I must classify as vicarious because it happens in my body but is not entirely of my body. Nor is the pleasure my property. It is Ben Dodge’s property.

The performance is bizarrely masterful—though it’s not exactly clear what’s being mastered, or performed. Like a star on the red carpet, each sentence stops for photos, basking in its shapeliness, emitting its disciplined gleam. Look at the expert plotting of l sounds, the pivot of the last two lines; every single Koestenbaum syllable is buttoned tightly into syntax. Even the blips and eccentricities exert a snug control. Note the choice of “pleasure I must classify as vicarious” instead of the more obvious “vicarious pleasure,” as if to tease, invert, rule the phrase, subjecting it to brutal prolongation and a finicky exquisiteness. But the passage appears in his book Humiliation (2011)—so the entire fussy vessel flips over in an abject splash: “It is Ben Dodge’s property.”

These are gay sentences. Or rather, the self-dramatizing, self-defeating, brilliantly specific sensibility expressed with thrilling tautness across Koestenbaum’s writing for thirty-five years—an oeuvre that includes poems, criticism, book-length essays, biographical studies, fiction (rare), and a single academic monograph (on male literary collaboration)—arrives at a fantastic, mix-and-match synthesis of a century of gay white taste. “Sick of the cult of muscle among the queer (myself included), I have developed a style, borrowing from self-conscious femmes like Ronald Firbank, that derives its tangential power from the deliberate avoidance of the appearance of masculinity,” he pronounces in the 1994 essay “ ‘My’ Masculinity,” reprinted in the collection Cleavage (2000). “I wonder if secret, underwater masculinity accrues through this pose.”

It does, and it doesn’t. Here’s a line from his new book, Stubble Archipelago, made up of poems that he’s called “something sonnet-like”:

Dog’s tail resembles flapping human penis: I need

to become better

acquainted with all

mammalian anatomy.

“Mammalian anatomy”: the grandiloquence amounts to a stumble, a bit of practiced syllabic slapstick. Crudeness cut with pomp: it’s tempting to call this camp. But Koestenbaum may be too elegant, too erudite, all the tension and delectation too touched by modernist seriousness and classical notions of virtuosity. Yes, he has a book of poems called Camp Marmalade. But even saying the word out loud suggests that his link to the thing itself may be—gallantly—custodial. Camp will always have a place here; it plays an important role. Proficiency in it tightens his kingly grip on what you might call the Queen Canon. This mastery may qualify as “underwater masculinity,” as his collection My 1980s (2013) seems to seize the whole territory: Hart Crane, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Frank O’Hara, Debbie Harry, James Schuyler, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, John Ashbery, Andy Warhol’s interviews (Koestenbaum’s 2001 study Andy Warhol may be a perfect book), and the soprano Anna Moffo (his avowed obsession, and a fixture of his work) are all treated to an essay each, and I’ve already mentioned the piece on Elizabeth Hardwick’s sentences.

Not obscure or unexpected subjects, perhaps. But their juxtaposition reveals something crucial about Koestenbaum’s presence on the page. Namely that the mannerist stylishness is more than pantomime of the Great American Essayists (Sontag, Hardwick), and he’s not just recapitulating the gestures of the art world–proximate New York School poets (O’Hara, Ashbery, Schuyler). Nor does the frontality of Koestenbaum’s ethos limit itself to glassy pop opacity (Harry) or an immanent-cum-recalcitrant contemplation thereof (Warhol).

Stubble Archipelago clarifies anew that we have been dealing with a theorist—an angular, taxonomical, nimbly systematizing temperament (Sedgwick, Barthes). Theory itself is the clicking mechanism that lets him manage these disparate registers, sometimes making of the quasi-sonnets a declarative, if fanciful, exercise in structuralism: “Aliveness a consequence of other alive people / attesting to your / lifelikeness.” A sentence can build and dismantle its own portable Oedipal apparatus: “If you never knew your father’s parents, / your father becomes / more of a void.” There is of course the classic Koestenbaum idiosyncrasy—the lovely sense that a phrase is a jagged, wacky space, paved neatly with the cobblestones of consonance and assonance: “Butt-crack, male phenomenon, rampant in airport—.” His earlier Pink Trance trilogy comprised poems composed in a state of near-hallucinatory exhaustion, an avant-garde automatic writing prompt adapted to an era of overwork; the poems in Stubble Archipelago are the products of routine walks through New York, a return to flânerie in a city gridded by Grindr and Uber.

If the theoretical preoccupation of this text seems more pronounced, it may be that these staged collisions precipitate a new type of longing, a new form of stylized futility, in the face of what New York is and has become. “Prison and school: both loom hard / against riot- / tending horizon”: I don’t remember anything like that in Koestenbaum’s earlier work. As he told Tausif Noor in (Andy Warhol’s) Interview, “It struck me when I started writing these poems that I didn’t sound like me any longer.” The word “capitalism” appears on this collection’s first page.

The result is a kind of Midtown Spleen. These poems are strangely—movingly—equal to the present, lying flush with features of the algorithmic everyday; but even critique must be stripped of its hauteur: “Adorno gave me, as stocking stuffer, this question: / is art’s protest / ‘mute and reified’?” The poet-critic Christopher Nealon coined the term “camp messianism” to describe how a handful of North American poets at the turn of the millennium fell back on that specific slanted affect to voice a jittery or embittered sense of political stasis; Koestenbaum here moves in the (dialectically) opposite direction. Today, what special place is left for flamboyance, given the glittering, triumphalist can-can of the commodity? “Compared to Ariana Grande, The Archies / sound like Schoenberg / tied up and force- / fed an overdose of Stevia.” If camp, to quote Sontag’s worst essay from her best period, responds the problem of “how to be a dandy in the age of mass culture,” then Stubble Archipelago suggests that the smashing, machinic profusion of plastic-packaged experiences is now taking place with more velocity than even the fiercest aestheticist appetite can possibly relish, savage, log, or judge. What does a love of vivid surfaces amount to amid the merciless, ubiquitous solicitations of the touch screen?

No answers—only the will for a less asphyxiating collective life, which, like all artifice, will have to be made. “Conjugate Adorno: adorno, adorni, adorna, / adorniamo . . .” he writes. From German to curling Italian; from proper noun to verb. I adorn, you adorn, she adorns. We adorn.

Tobi Haslett has written about art, film, and literature for n+1, Harper’s, and elsewhere.