Tobi Haslett

Tobi Haslett

From Pasolini to the Islamic State, the Lumières to Montesquieu:

Jean-Luc Godard offers his latest collage.

Still from The Image Book. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

The Image Book, directed by Jean-Luc Godard, now playing in New York

• • •

A throng of people leans forward, their hands thrust in the air and gripping little rectangles of plastic and metal—smartphones. Before them stands a man. He is white, graying, bespectacled, grinning, and blessed with what might be called avian good looks. He, too, is holding up a phone. But his is higher than the others; it seems somehow superior, or possessed, for one shocking moment, by some spirit or force or resplendent quality that compels the deference of the murmuring room. The whole scene vibrates with powerful yearning. One by one, members of the crowd approach the man’s device. A face looks out from the screen—it’s a man’s face, older than the other man’s, and it begins to speak. The voice is rough, weak, and slashed by irony, a disintegrating copy of a voice we know—full of seething wit and bombastic intelligence and punitive authority and kingly hauteur—the wheedling, lisping, iconic voice of the Swiss-French cineaste Jean-Luc Godard.

The eighty-seven-year-old has been summoned via FaceTime to a press conference at the 2018 Festival de Cannes, to address a room of critics who have just attended the world premiere of The Image Book. Godard is too weak to travel. So Fabrice Aragno—his cinematographer, coeditor, and coproducer—stands proudly before the press, brandishing Godard’s pixelated visage as the journalists approach with a question each. They’re rigid with admiration, transfixed by the Master’s floating face.

Jean-Luc Godard. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

I present this tableau, with its blend of sci-fi and sacred rite, because it captures something of the experience of seeing The Image Book—a work of such stabbing angularity, exorbitant allusiveness, unyielding digression, and exhausting doom that the film’s sole justification, the thing that joins and stabilizes all the rattling fragments, is the totemic allure of a name: Godard. The pleasures of this work (and yes, there are a few) are the ego-melting pleasures of supplication. If you’re not obsessed with the six decades of Godard’s career, the film will feel indulgent, even cruel. But if you happen to be abjectly fascinated by how Godard’s politics and brittle reflexivity have fed and mutilated his forbidding “late style”—The Image Book may please you. This is a graceless work. That gracelessness feels like a spiritual resource, a kind of optimism of the will.

Still from The Image Book. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

“There are the five fingers, the five senses, the five parts of the world,” Godard says in the first minute. The crisp elocution of his ’60s essay films has collapsed into a vulnerable groan. And as in Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1989–99), the ten-year project that serves as a sprawling intellectual root system for Godard’s subsequent collage works, The Image Book consists almost entirely of footage that spans cinema since its birth. The clips are perplexing and bracingly brief. They’ve been shredded into little flashes, to catch a gesture or a single look, which are cannily slotted into one of the film’s five parts. Parts that I, with appalling vulgarity, will now attempt to gloss.

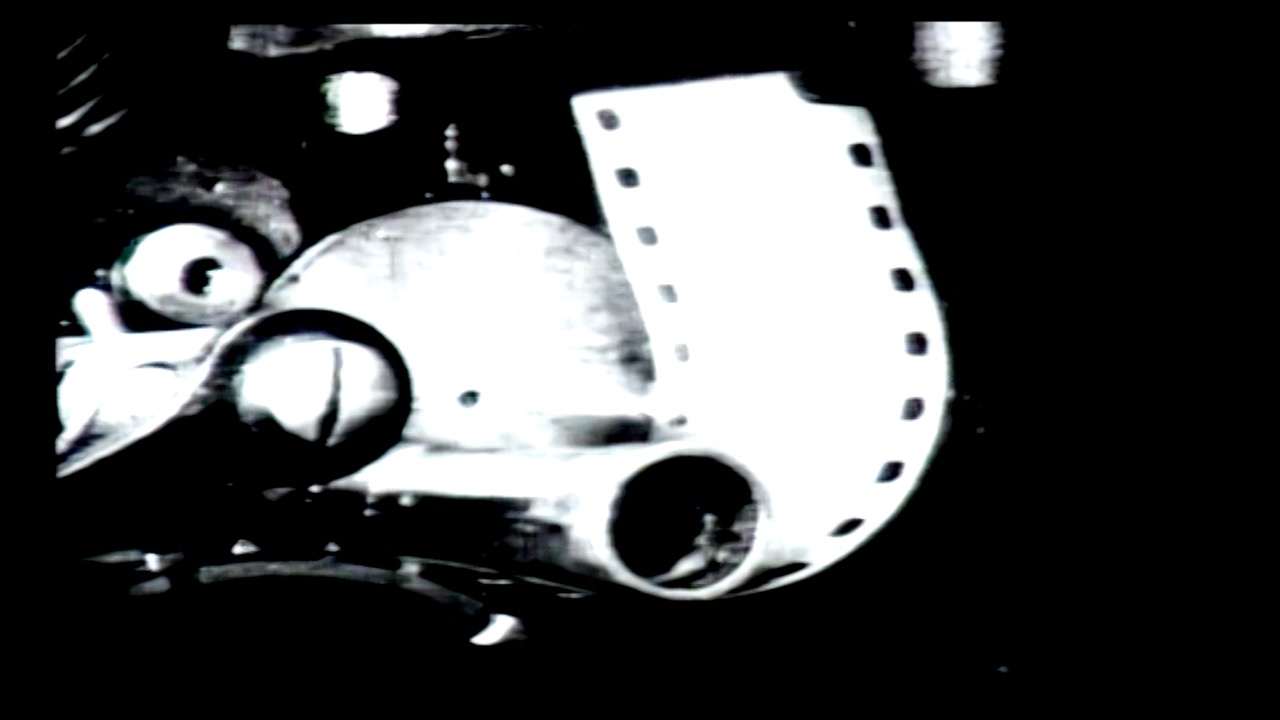

“Remakes,” the first section, appears to have some vague relation to regimentation, symmetry, fraud—anything to do with multiplicity or doubling. Scottie saves Madeleine from drowning in Vertigo; the eighteen teenage slaves from Saló (Pasolini’s adaptation of Sade) crawl naked through a marble hall; and Anna Karina in Le petit soldat, Godard’s 1963 film about a man suspected of being a double agent, says, “I’m not in love with you.” Blurry video footage of the Islamic State at first seems inane or out of place, until you remember that the group’s explicit mission is to resurrect a medieval caliphate—“remakes,” indeed. The second section is “St. Petersburg’s Evenings,” and seems to be about licentious empires and the people who hate them (there are a few references to czarism and Joseph de Maistre, and a picture of red carnations laid at Rosa Luxemburg’s grave). “These Flowers Between the Rails, in the Confused Wind of Travels” plucks a line from Rilke—and as the third part, offers both a tour of trains in cinema and some of this film’s most poignant passages. Godard deigns, here, to sustain a visual melody. This section is also a prettily extended citation of one of the very first works of cinema—the Lumière brothers’ L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, whose image of a rushing locomotive is said to have terrified the 1896 audience who thought they saw a real train barreling into the theater.

Still from The Image Book. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

Goodbye to Language (2014), Godard’s previous film, revived some of that visual shock: the project was shot in 3-D and is perhaps the loveliest and most sophisticated of his collages. Images bloom and swing out from the screen, as old footage is voluptuously refreshed. But in The Image Book, the picture looks clammy and embalmed, since everything has been dribbled through the sieve of Aragno’s process of analog recoding, digital reinscription, and distortion—which produces a drained, processed, somehow vinegary visual effect. (This technique is present in Goodbye to Language, but is diluted by the 3-D.) “The Spirit of the Laws,” section four of The Image Book, draws quite literally from the Montesquieu text of that name, and includes one of my favorite shots from Godard’s Tout va bien—of the striking Maoist workers surrendering to the police as smoke from an explosion twists brutally into the sky. But here the image from that 1972 film is a sickly facsimile—digitally pickled.

The blasted, virtuous struggle, rendered bloodless and abstract by the passage of time: the scene telegraphs the sensibility that rules all of Godard’s late work. The Image Book belongs to that robust genre, the soaring lament of the humiliated Marxist. The fifth section, “La Région Centrale” (also the title of a work by Michael Snow, as Amy Taubin reminds us in her Artforum review), features a line uttered by the strained voice that begins the film: “C’est l’angoisse.” And finally, “Joyful Arabia” is a kind of postscript for The Image Book and draws from a novel by the French-Egyptian novelist Albert Cossery. It tells the story of Dofa, a fictional Arab country that has been spared imperial incursions because there’s no oil beneath the sand. But a few maniacs insist on making revolution.

Still from The Image Book. Image courtesy Kino Lorber.

It occurred to me that Dofa might be Godard’s latest hyperbole for the cinematic screen: without oil, the country is a vast, total surface, available for ideological conflict and the fantasy of revolt. In Godard’s Maoist period, he filmed fists defacing or punching through the screen; in Goodbye to Language, it merely flexes and ripples. Freed from the rigors of dialectics by the failure of the New Left, Godard now stalks Lear-like over the heath of his own devastated feelings. “There must be a revolution,” he announces at the end of The Image Book—but the militant’s devotion to theory and praxis has lapsed into a wistful wobble between experience and loss. So Godard is thrown back on a desperate messianism. At the film’s end we hear track over track of his hacking, failing, heaving, spluttering, now-ancestral voice, which says, beneath the layers of pain: “Ardent espoir”—ardent hope. The words arc through the mind.

Tobi Haslett was born in New York. He has written about art, film, and literature for n+1, the New Yorker, Artforum, the Village Voice, and elsewhere. He is currently a doctoral student in English at Yale.