Will Heinrich

Will Heinrich

After Open Casket: the artist exhibits new painting and sculpture.

Dana Schutz: Imagine Me and You, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

Dana Schutz: Imagine Me and You, Petzel Gallery, 456 West Eighteenth Street, New York City, through February 23, 2019

• • •

To judge from the dozen enormous paintings and five small bronzes in her powerful new show—the artist’s first New York gallery solo since a disastrously ill-judged entry in the 2017 Whitney Biennial—Dana Schutz has fallen to earth. That entry, the now-infamous Open Casket (2016), depicts the body of Emmett Till, whose mother famously gave him a public, open-casket funeral after he was lynched, at the age of fourteen, in 1955. Schutz was widely criticized for casually appropriating an iconic image of black martyrdom. She was also, more specifically, criticized for her treatment of that image in paint—for partially abstracting the boy’s face, in a gesture presumably intended to acknowledge the violence of which he was a victim but which some read, instead, as recapitulating it. The painting drew fierce protests and even calls for the work to be destroyed. But the severe blowback to that Whitney mistake appears to have knocked Schutz into a heavier, more reflective, and altogether more deeply felt place.

Dana Schutz, Building the Boat While Sailing, 2012. Oil on canvas, 120 × 156 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

Start by looking back to Building the Boat While Sailing, an overstuffed explosion of strange, frozen figures Schutz painted five years before the Whitney debacle. It’s full of visual puns—a water spout that’s also a cloud, lines of motion that read as a seagull. Because the paint is so thinly applied, because the drawing is so cartoonish, and because the vista’s overall mood is so bright, these puns come off as nods to the intoxicating mutability of flatness—cheerful little reminders that a two-dimensional picture is a world apart.

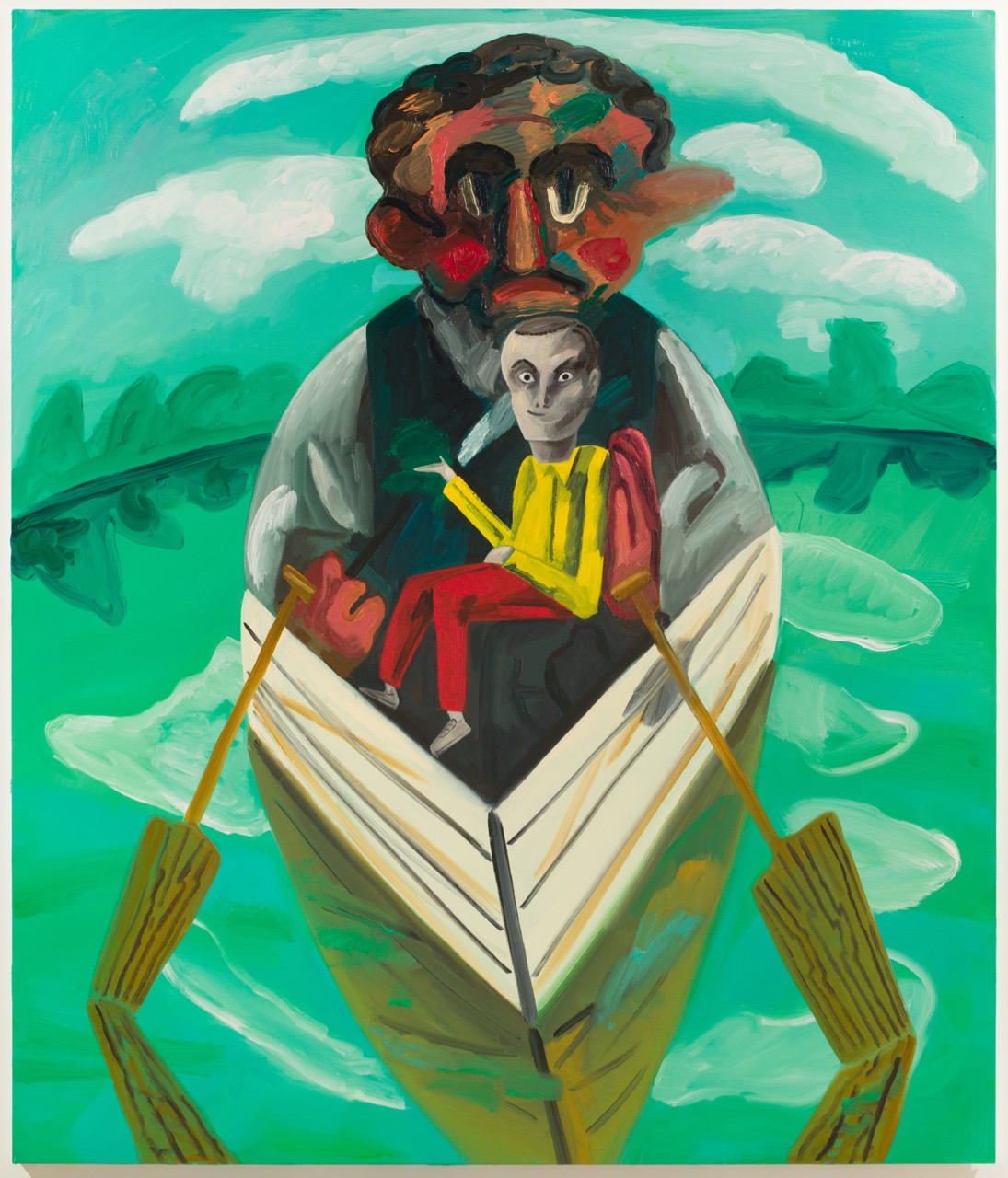

Dana Schutz, Boatman, 2018. Oil on canvas, 88 × 75 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

Compare this to 2018’s Boatman. (Everything in the new show was made in the last year.) A lugubrious man sits in a tiny rowboat with a corpse-colored mannequin in his lap. The two visible sides of the boat, descending in an exaggerated V, look as much like the wings of a crashing model airplane as they do like a boat. Here visual ambiguity is presented not as a fun aside but as the painting’s central subject. The heavy impasto Schutz has started using means that no one could mistake this for a statement about flatness, though it’s still obsessively preoccupied with the process of art making. (The man’s lumpy, color-bruised face evokes a used palette, and the figure in his lap could be an idealized self that he’s just made out of clay.) Moreover, unlike her earlier double readings, which flipped effortlessly back and forth, the boat’s confusing perspective is defiantly unresolved.

Dana Schutz: Imagine Me and You, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

Ambiguity fuses with attention to process in the first sculptures Schutz has ever exhibited, an appealing group of headless gnomes and crocodile demons displayed on waist-high white plinths. The pieces are cast in bronze with a grayish patina, but because Schutz has roughed up their surfaces with squiggles, troughs, and finger holes, they register, at first, as clay. Something about their color, though, or the way they reflect light, doesn’t quite scan, so even after I had looked them over and consulted the checklist, part of my mind’s eye kept trying to figure out what they were made of.

Dana Schutz, Treadmill, 2018. Oil on canvas, 90 × 96 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

An eight-foot-high painting called Treadmill shows a rufous, frog-faced creature running in place beside a blank blue rectangle. Red and blue scribbles droop from the back of its head as sweat, hair, or incarnate hysteria. In The Visible World, a naked white woman, bound to a skerry as if in offering to a sea monster, turns her strangely armor-like torso directly at the viewer. A funnel of blue sky pours between dark gray clouds onto the woman’s head as she thrusts one pointing finger down into a tidal crash of red and blue lines. It’s hard not to read these two images as a tone-deaf complaint about how hard the painter works and an over-the-top suggestion that her offering of such complaints to the public is akin to human sacrifice. But then what does it mean for Schutz to exhibit such unattractive ideas to the glaring scrutiny she knows she now inhabits?

Dana Schutz, The Visible World, 2018. Oil on canvas, 108 × 140 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

In Mountain Group, a motley crowd of grotesques huddles together atop an enormous gray rock. While a giant Muppet-like creature raises Vs for victory, nearly all the rest of the crowd are madly pointing—over here, over there, to the sky. There’s even one disembodied pink digit cocked at the angle of a cannon. None of the fingers quite succeeds in pointing at the painter kneeling meekly below them over a work in progress. But she’s not getting them, either: the picture she’s intent on is a banal, unpeopled mountainscape.

I don’t know what all this says about Schutz’s actual state of mind. But what it says, to me, about her paintings is that they’re no longer the buoyant, self-contained fantasies they used to be. Instead they’ve become attempts to grapple with the full weight of human experience, her own flaws and failures included.

Dana Schutz, Beat Out the Sun, 2018. Oil on canvas, 94 × 87 ½ inches. Image courtesy the artist and Petzel.

In a way, the intractable formal ambiguity of Schutz’s new work is itself the work’s chief insight, because it’s the aspect that most powerfully resonates with the real complexity of life. And it reaches its peak in Beat Out the Sun, in which a starving clan of clowns or hobos armed with femurs, broken glass, and two-by-fours marches shoulder to shoulder against a low-hanging sun. The men weep and grimace, but they’re surrounded by food: the solar orb is a hard-boiled egg yolk, its rays french fries, the clouds mashed potatoes. The sky behind them is stained with mustard and grease. Even their weapons are rashers of bacon. It’s a terrifying scene, a squalid cosmic battle with no good outcome possible. Either the hobos plunge the world into darkness or else they’re burnt alive . . . except they can’t reach the sun, anyway. As with Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa or the cow jumping over the moon, its nearness is a just trick of perspective—but a heartbreaking one.

Will Heinrich was born in Manhattan and spent his early childhood in Japan. His novel The King’s Evil, published by Scribner in 2003, won a PEN/Robert Bingham Fellowship in 2004. He currently lives in Queens with his wife and daughter and writes about art for the New York Times.