Tobi Haslett

Tobi Haslett

A MoMA PS1 show collects work made in response to the Gulf wars.

Jamal Penjweny, work from the series Saddam is Here, 2010. Photograph, 23 2/3 × 31 1/2 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011, curated by Peter Eleey and Ruba Katrib, MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Queens, through March 1, 2020

• • •

I am a child of these wars—which is to say that their obscenity forms the backdrop of all I know about the world. Every shred of my awareness of the global grid of exploitation relates to and even follows from an irrefutable reality: that there’s a place, called Iraq, that’s faced relentless devastations for all my life and in my name. For a few American civilians more or less my age, the Iraq catastrophe has served perversely as a kind of education: in protest, and its failure; in the force of wartime rhetoric, no matter how garbled or depraved; in the voracity of global capital and the servility of the mainstream press; in the attachment of American liberals to their invertebrate ideology; and in the US’s role as “the world’s policeman,” who, like all cops, hunts the poor. These lessons swirled to mind on my three visits to MoMA PS1, where every floor now houses artworks prompted by the “engagement” in Iraq.

Thomas Hirschhorn, Hotel Democracy, 2003 (installation view). Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Curated by Peter Eleey and Ruba Katrib, Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011 is sliced along several axes: between work about the first war and the second, and between artists from the West and the Middle East—and, within the latter, between those who saw the conflicts firsthand and from the aching safety of diaspora. The show proceeds chronologically: the basement and first floor pertain to Desert Storm, waged in 1991, the upper levels to Iraqi Freedom, launched in 2003 and later rebranded New Dawn. It should be said upfront that the approach of the more illustrious artists here tends to the banal and smoothly dutiful—war feels like an input plugged into the spreadsheet of their practice. These Jenny Holzer LED displays are actually about Iraq; the plump figure in this Fernando Botero painting is a prisoner at Abu Ghraib. And Hotel Democracy (2003), the colossal Thomas Hirschhorn piece that’s this show’s lavish, prestigious climax, rhymes with his monuments elsewhere in a way I found less intriguing than simply glib.

Afifa Aleiby, Gulf War, 1991. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 × 27 1/2 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

But Theater of Operations is also a corrective—a chance to show Gulf artists in the nation of their torturers. The Iraqi painter Afifa Aleiby’s canvases present elegant allegories of demise: in Gulf War (1991) a robed female figure is flung against a Mesopotamian bas-relief shredded by bullets. Nuha al-Radi’s Embargo Series is made up of sculpted humanoids built from scavenged wood and metal (in the absence, during interwar UN sanctions, of more deluxe materials). And paintings by the late Kuwaiti artist Khalifa Qattan greet you on the first floor: five churning, mystic pieces full of twisted faces and rent flesh. Most of these were made between the 1960s and 1980s. After living through the 1990 Iraqi invasion, Qattan dubbed the works “prophetic.” So the link between art and “testament” is snapped—or at the very least smudged. The move prompts a question that cannot help but stalk this show: How should we look at those art objects that spring from crisis but shrink from witness?

Nuha al-Radi, Embargo Sculpture, 2000–03 (installation view). Photo: Matthew Septimus.

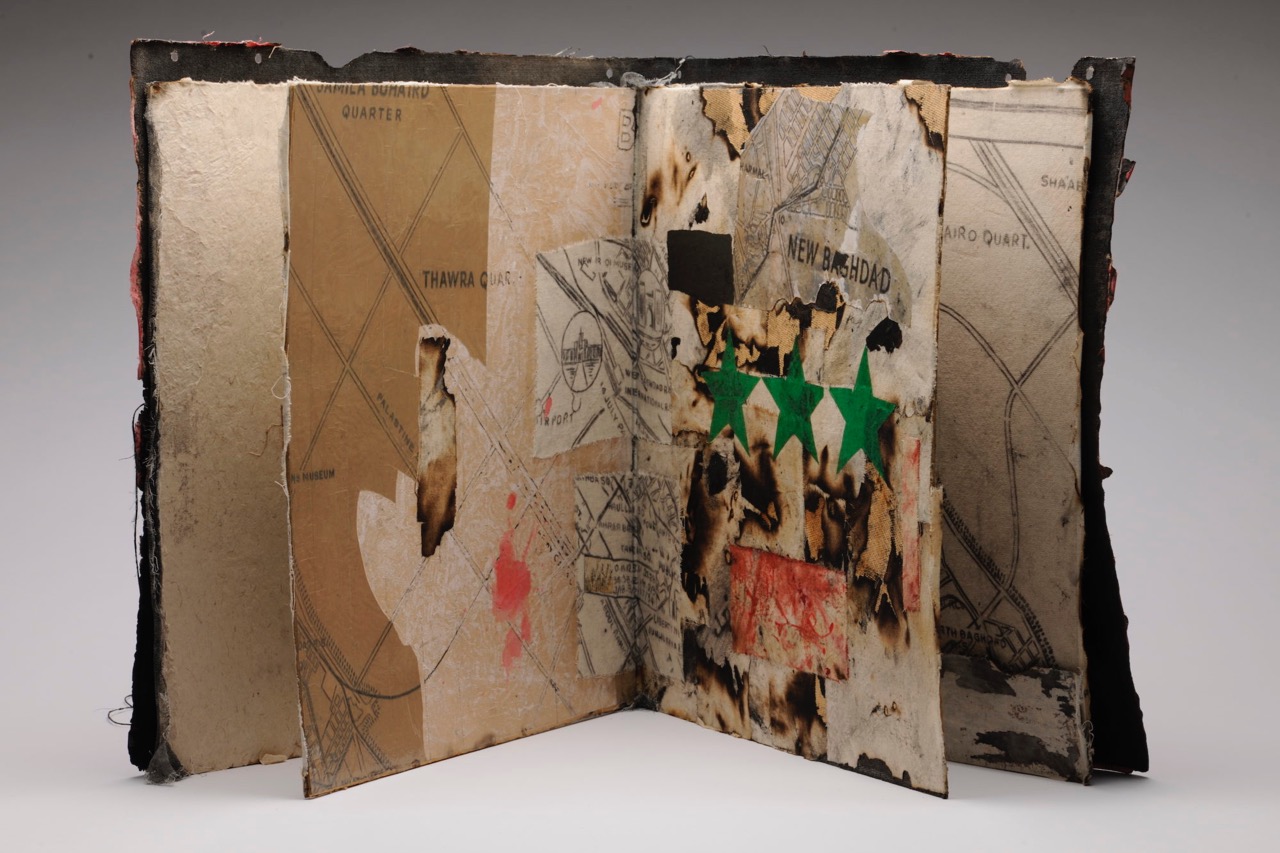

To which the curators have responded by displaying various dafatir: a medium that flourished in Iraq during the decade and a half of cataclysmic sanctions, an era of economic implosion in which artists, lacking materials, were forced into a bitter ingenuity. The result are artists’ books—dafatir is the plural of daftar, the Arabic word for notebook—which dot the whole museum, the modesty of their scale and construction ennobled by vitrines. This is the expression of a starved people, a people out of joint and under fire. Exposing these pieces—many of which are by Kareem Risan and Dia al-Azzawi—to a New York audience is among this show’s indisputable virtues. But these are fold-out books, intended to be handled and flipped through in a form of tactile delectation. At PS1 they’re (by necessity) trapped beneath the glass—pinned like lepidoptera and splayed open to just one page.

Hanaa Malallah, Baghdad City: US Map, 2007. Mixed media (ink, collage, burning, and tape on wood), 20 7/8 × 21 5/8 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Azzawi Collection. Photo: Anthony Dawton.

The object is inaccessible, almost inapprehensible, a screen for our projections and guilty dreams. Fitting, perhaps—since the first Gulf War was purportedly pitched on the slick terrain of the simulacrum. “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place,” the infamous 1991 essay by Jean Baudrillard that wobbles between modishness and outright crankery, is excerpted in the exhibition catalog and names a fear that grips the show. The first Gulf War was subject to constant, exorbitant, startlingly intricate TV coverage. But as a “surgical war,” it was sold to the West as an exercise in bloodless virtuality. Hence Michel Auder’s video Gulf War TV War, made in 1991 but edited in 2017, which flashes across a massive wall and projects cable news talking heads reduced to a froth of authoritative articulation. They’re at a feckless, nattering distance from the screams and falling bombs.

Michel Auder, Gulf War TV War, 1991 / edited 2017 (still). Hi8 video and mini-DV transferred to digital video, 102 minutes. Image courtesy the artist and Martos Gallery.

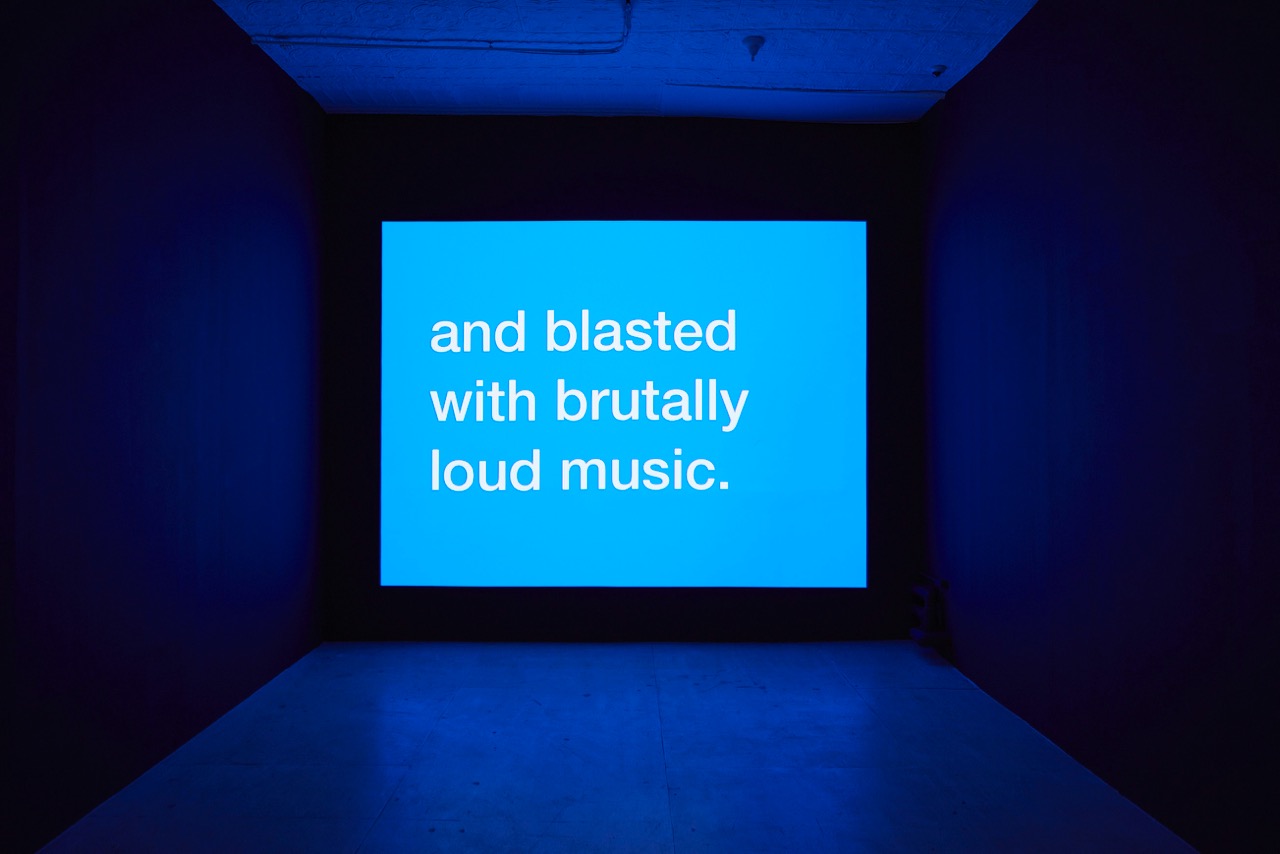

So for all the glimmering, voluptuous flexion of post-structuralist indeterminacy, the show sits cheek by jowl with a scorching insight of Western Marxism—that “there has never been a document of culture,” in Walter Benjamin’s oft-quoted words, “which is not simultaneously one of barbarism.” That barbarism is made explicit, sickly literal, in the videos of Tony Cokes. The didacticism of his work clicks intelligently between vicious and grimly piquant, and his Evil.16: (Torture.Musik) (2009–11) is one of the most powerful pieces in the show. A huge video fills a wall with text that explains how US torturers blasted Western music—rap, metal, pop, rock—at sadistic volume and traumatic length to shatter the psyches of their captives. “Disco isn’t dead,” proclaims Cokes’s video, as the soundtrack floods the room. “It has gone to war.”

Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011, installation view. Image courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

As has contemporary art. Leon Black is the founder of the equity firm Apollo Global Management, which owns Constellis—which acquired the military security group formerly known as Blackwater USA, which was banned from Iraq in 2007 after its personnel were involved in a shooting that left at least seventeen Iraqis dead. Larry Fink serves as the CEO and chairman of BlackRock, an investment firm that holds shares in CoreCivic and GEO Group, which together manage an enormous complex of immigration detention centers across this country, where children, ripped from their families, are notoriously forced into cages. Both Black and Fink are trustees of MoMA—and targets of protests by two artists in this show. (PS1 has a different board but nevertheless bears the MoMA name.) Phil Collins withdrew his video baghdad screentests (2002) just before the exhibition opened. And Michael Rakowitz—who was also the first person to boycott the 2019 Whitney Biennial in protest of the arms manufacturer and museum trustee Warren Kanders—has requested that the video component of his work Return (2004–ongoing) be paused. MoMA PS1 has refused. But “with the presentation of Theater of Operations,” the museum insisted in a statement, “we remain focused on the global effects of the Gulf wars in Iraq—particularly in the context of the current political turmoil there.”

By which they mean the demonstrations that came thrashing to life this autumn and now may constitute the largest popular uprising in the history of Iraq: a mass rebuke—overwhelming the sects and political parties—to the ecocide, immiseration, and infrastructural collapse that have followed the endlessly replenished violence of the late-imperial appetite. Over five hundred Iraqi civilians have been killed since the movement began in October. The significance of this exhibition, which was planned years in advance, has thus been changed, slashed fiercely open, by the excruciating history it endeavors to enshrine. Ali Eyal, born in 1994, is the youngest artist in the show; he has only ever known Iraq as economically gutted and/or held hostage by the West. In one of his pieces, he’s used pillowcases as a surface to paint his family’s descriptions of their dreams. Like revolution, each dream is dark, striking, cryptic, thrilling, enticing in its implications but rooted in a vast hurt—and stands at the brutal threshold between suffering and meaning.

Tobi Haslett is a writer living in New York.