Jeanine Herman

Jeanine Herman

Tess of the suburbanvilles and pills: in Natasha Stagg’s second novel, a woman looks back on her tumultuous early-2000s adolescence.

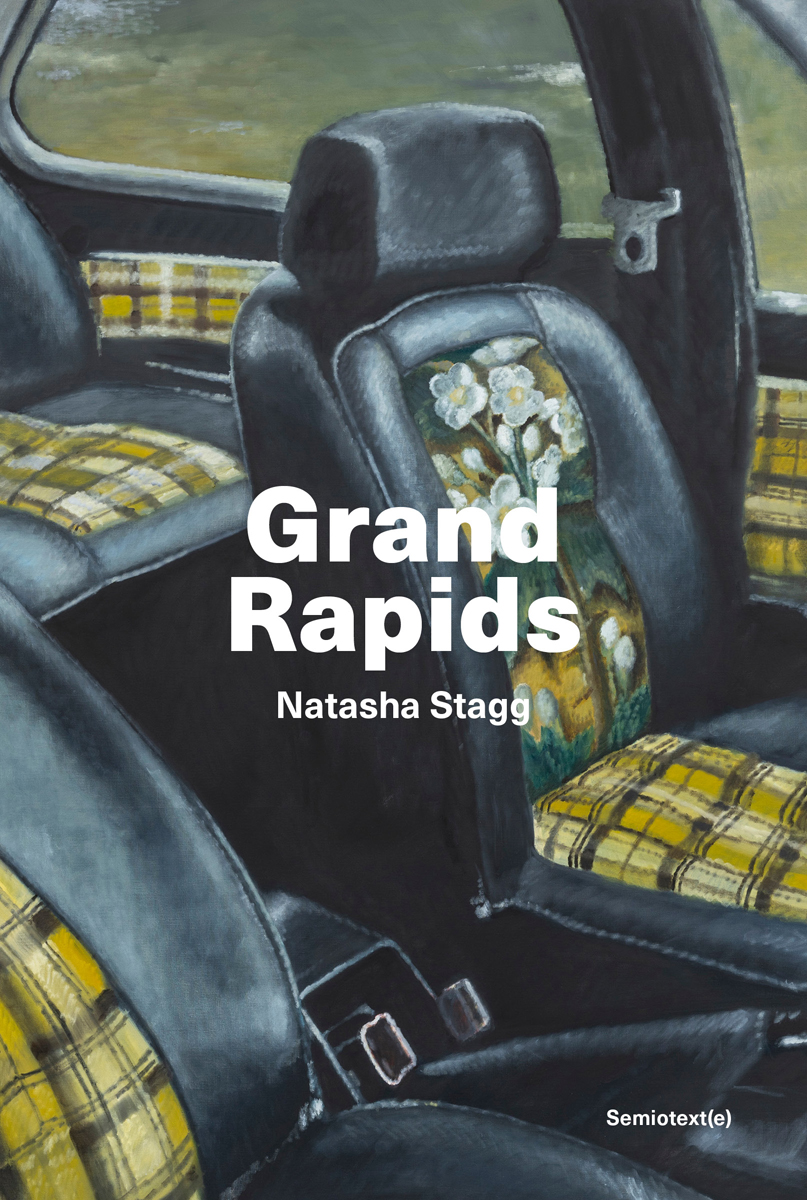

Grand Rapids, by Natasha Stagg,

Semiotext(e), 221 pages, $17.95

• • •

Told in flashbacks to someone asking where she grew up (we don’t know if they’re a date, a friend, or what), the book is a reply to that question, in the form of a teenage diary, the story of Tess as an adolescent girl. “I’m telling you all this because you asked. . . .”

Her youth is tumultuous after her parents’ divorce; her mother moves them from Ypsilanti, Michigan, to live with her sister in the larger, more affluent Grand Rapids, and then she gets diagnosed.

As Tess’s mother is dying, skater boys outside the hospital do tricks in their “Gumby pants.”

After her mother dies, the narrator refers to her as Sheila.

“Since Sheila was diagnosed, I was the inconsolable child, the piously loving daughter, the hardened early adult, the inconsiderate kid, the diagnosed depressed teenager, the medicated person. Even before the medication, though, I started to feel and see things like the symptoms of nervous disorders.”

This is, in a sense, a memoir of Tess’s nervous illness.

• • •

Tess is very alone.

“I had never been this alone in my short little life so far, I thought.”

Though her new family makes an effort to welcome her, she feels alienated. She is on Prozac, living in the basement of her aunt’s house, going to a new school, and working in a nursing home—her life does seem pretty grim. She admits that she feels a bit like Cinderella.

In the facility where she works:

“The residents filed in, pushed by nurses. It was still early. Their faces were like mountains as seen from a plane, shadowed by little clouds.”

She makes some friends (Candy, Lauren). Lauren listens to “fast punk rock” and drives a yellow Karmann Ghia. Candy—pale, with a penchant for PJ Harvey—leaves Tess a CD.

“That Sunday . . . there was a CD jewel case on the doorstep. It said, in permanent marker, ‘For Tess,’ inside of a heart.”

She kisses Candy, but she also starts going to the coffee shop downtown with Lauren and develops crushes on some of the guys there.

She has crushes on girls; she has crushes on boys; she’s casting about.

They have boyfriends, but Tess and Candy are also in love.

She has the internet, TV, drugs, and music.

She watches a reality show with her new family about wealthy women in Grosse Pointe. That seems to speak to all of them.

“On TV, the trophy wives were somehow the stars. They could get their husbands to give them rich lives, simply by being beautiful. Their beauty had faded but the agreement was in place. Maybe there were indiscretions, but in the end the knowledge remained: someone with a lot of money was willing to pay for a woman’s entire life, simply because she had asked him to.”

She is trying to understand the transactional nature of certain arrangements.

• • •

She doesn’t want people to pity her, but she also manipulates the fact that they do, a little bit. She’s acting out, acting up, lashing out. She’s seeking oblivion.

Early-aughts suburban rebellion looks like hanging out at the coffee shop near the gas station and liquor store with druggy, hardscrabble, marginal people. It’s looking for something other than hunting, fishing, football, and church.

Tess is unruly, bereft, adrift. She wants a different aesthetic:

“I’d thought that moving away from my friends, into a big house surrounded by horses and churches, to a new school full of spoiled blonde ingrates, gave me license to change my look to something more severe. Sheila didn’t mind that I’d started lining my eyes and cutting thrift store skirts short. She appreciated the creativity. And then I lived through the ultimate severity, and so I’d earned an even harsher look.”

She is getting high on cough syrup and dying her hair black with Candy:

“We made a mess, staining the edges of the sink and rugs with dark purple drops of dye, as thick and toxic as the syrup we drank.”

“My swirl of hair was dimensionless in the mirror yet it dripped iridescence in the sink.”

When she rinses it out in the shower:

“The bottom filled with black that thinned to violet and magenta in beautiful streams and I yelled that it looked crazy.”

Velocity, ferocity, viscosity.

• • •

She gets a prescription from her therapist.

“I was already high all the time but getting higher offered a spectrum of brighter experiences, a piece of glass held up to a drifting beam of light.”

“I spent whole days in bed, staring at patterns the sun made on my door . . .”

After her mother dies, Tess feels like she’s losing her mind. But the pain of losing her mother is countered, somehow, Tess says, by this sense of going insane.

There is also her dead mother’s diary. This is kept in the bathroom under the sink with Tess’s self-harm equipment (a lighter). Tess does self-harm—burning her arm, branding herself—because one pain replaces the other.

“Hours of my life were lost due to the ingestion of dextromethorphan, clonazepam, alprazolam, promethazine, codeine, oxycodone, alcohol mixed with fluoxetine and caffeine, a couple mystery drugs, and pressed pills. Every time I dissociated, it was either the start of a nervous disorder, a new side effect, or something working its way through my system from the night before. I’d held onto a concrete wall because I had to. I’d been taken to the school nurse, kept in a little room with a cool towel on my forehead. She let me stay for as long as I wanted. Mostly, she said, she dealt with liars.”

Memories blend together, are painted over. There are images of tide pools, treading water.

The book is made of shards and fragments pieced together like one of those rustic roofs in the countryside made of uneven tiles that form a perfect circle.

As I was reading this book, a song came on the radio: “Candy,” by Iggy Pop. It seemed felicitous. For Tess, it is a point of pride that Iggy Pop is from Michigan and grew up in Ypsilanti. And, like Iggy in this song, she can’t let go of Candy.

Candy, Candy, Candy, I can’t let you go.

Tess is grief-laden and fairly reckless.

Amid the abject and the sordid, though, the book glitters with moments of beauty. There is a tender scene with a resident in the nursing home, as well as the final paragraph of the novel, which is a kind of shimmering tour de force.

There is a hole in her heart. There is the soft, gray sky, and “the green, churning river,” which is naturally fleeting and irretrievable. So is this time in Tess’s life, deftly captured here by Natasha Stagg.

Jeanine Herman is the translator of Laure: The Collected Writings (City Lights Books), Archeology of Violence by Pierre Clastres (Semiotext(e) / MIT Press), and A Woman of Thirty by Honoré de Balzac, forthcoming from New York Review Books.