Margaret Sundell

Margaret Sundell

The first solo show outside France of the Canadian artist, who died in her early thirties in 1983, presents tantalizing works haunted by an atmosphere of absence and loss.

Alix Cléo Roubaud: Correction of perspective in my bedroom, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz.

Alix Cléo Roubaud: Correction of perspective in my bedroom, curated by Hélène Giannecchini, Galerie Buchholz, 17 East Eighty-Second Street, New York City, through October 25, 2025

• • •

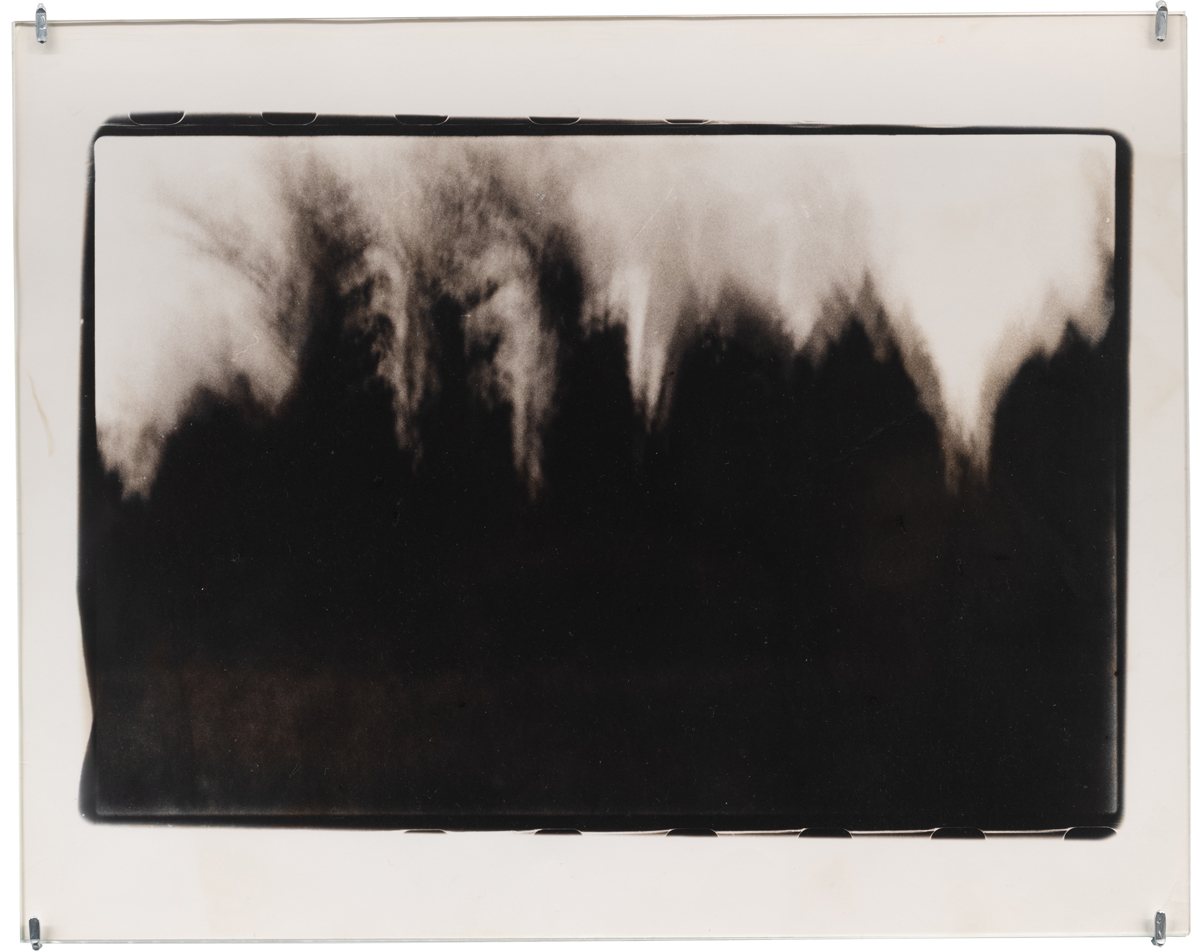

The daughter of a diplomat father and a painter mother, Canadian photographer Alix Cléo Roubaud (1952–83) was born in Mexico City and grew up in far-flung locales before settling in Paris at the age of twenty-three. She died of a pulmonary embolism eight short years later, her lungs ravaged by the severe asthma she suffered throughout her life. Untitled (Fifteen minutes at night to the rhythm of breath) (1980) creates an embodied image of the disease’s effects. Lying on her back with a camera held to her chest, Roubaud shot up into a group of cypresses using an extremely long exposure of ten to fifteen minutes. The shifting of the apparatus, which causes the trees to blur, registers her labored respiration.

Alix Cléo Roubaud, Untitled (Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration / Fifteen minutes at night to the rhythm of breath), 1980. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz.

At the time of Roubaud’s passing, her art was barely known. It was up to others to secure her reputation. Luckily, she had champions: her husband, the renowned avant-garde poet Jacques Roubaud, who penned a book of verse in her memory and published selections from her journals; her lover, Jean Eustache, whose Les photos d’Alix won a César for best short fiction film in 1982; and art historian Hélène Giannecchini, who has dedicated a large portion of her career to the photographer—archiving her pictures and papers, writing the biography Alix Cléo Roubaud: a portrait in fragments, and curating exhibitions of her work, most recently her first solo show outside France, now on view at Galerie Buchholz.

Alix Cléo Roubaud: Correction of perspective in my bedroom, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz.

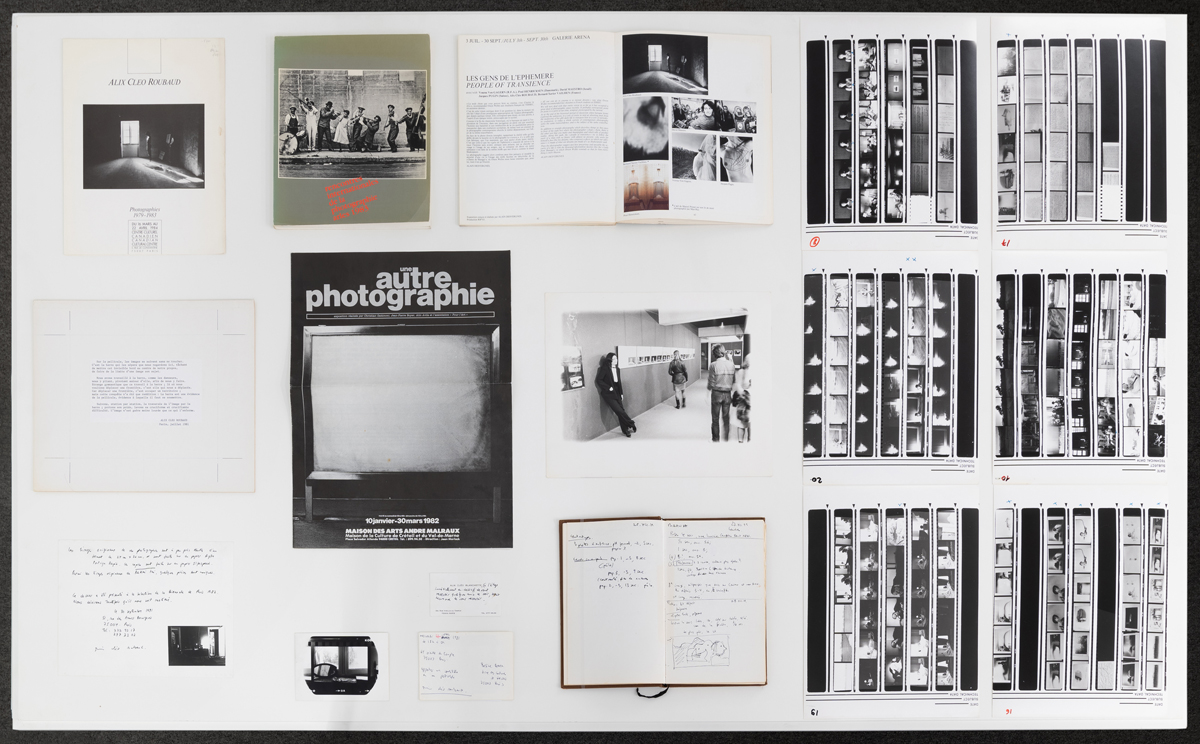

Thirty-nine small-scale gelatin silver prints adorn the gallery walls, including in the back room, which also features related publications, contact sheets, and ephemera. For those, like me, who were treated to a tantalizing glimpse of Roubaud’s work last year in Forks & Spoons (a group exhibit at Buchholz curated by artist Moyra Davey) and who devoured the newly translated English-language version of Giannecchini’s 2014 study, this exhibition is particularly welcome.

Alix Cléo Roubaud: Correction of perspective in my bedroom, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz. Pictured: Correction of perspective in my bedroom series, 1980.

Roubaud attended photography courses as an undergraduate but took up the medium in earnest in 1979. Her practice was exploratory by nature. Laboring for up to ten hours on a single print, she deployed and refined the darkroom techniques that were a staple of her oeuvre. She used dodging techniques to block out unwanted portions of a negative or drew on its photosensitive surface, sometimes exposing it with a pen light to create a strong black streak in the final print; she played with multiple exposures, as seen in many of the pictures on view.

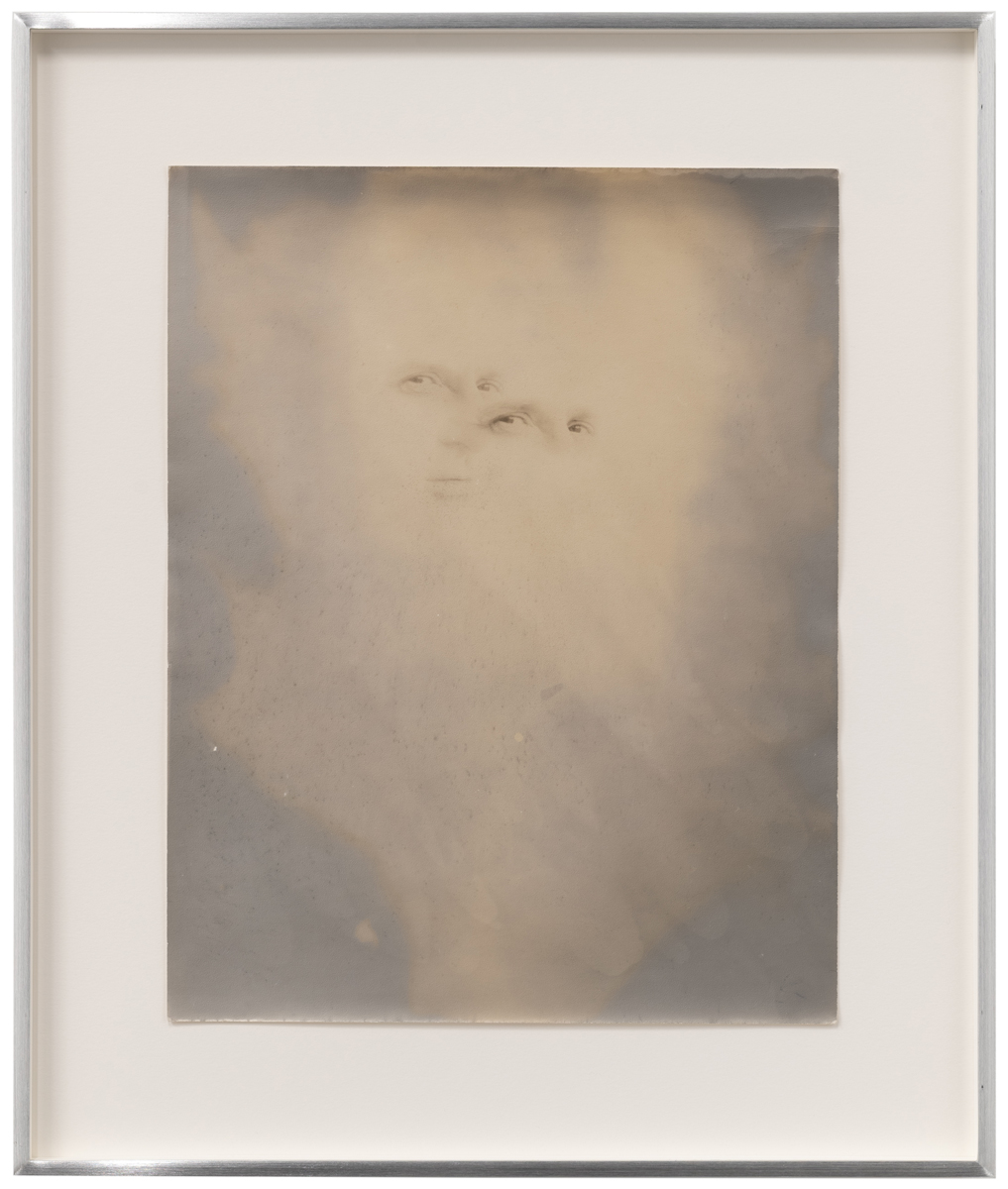

Alix Cléo Roubaud, Les yeux de la mère / The mother’s eyes, 4, 1981. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz.

In one, two sets of eyes peer out of a white expanse of unexposed paper. The work’s title reveals that they belong to the photographer’s mother, with whom she had a tense relationship. The difficulties began when Roubaud was fifteen and started a passionate affair with a woman around twice her age; her mother discovered the liaison and intervened. Do these eyes represent the scrutiny to which the adolescent felt herself subjected? Using a multiple exposure and withholding light from most of the negative, she makes of her mother nothing but a vigilant, doubled gaze.

Alix Cléo Roubaud: Correction of perspective in my bedroom, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz. Pictured, both: Untitled, ca. 1980–82.

Roubaud reaches further back into her youth in Untitled (ca. 1980–82). Made with a negative of a photo taken when she lived in Egypt, the picture shows the artist as a little girl sitting in a grove of palms. Both elements are underexposed, thus washed out and pale, in particular the young Roubaud, who just passes the threshold of visibility. She is there, but barely perceptible in this resonant image, which yokes photography’s evidentiary capacity to experimental techniques in order to express the vicissitudes and instabilities of memory. A pendant scene, also Untitled (ca. 1980–82), layers the palms again and again to create a dense forest, the Sphinx lurking deep within its interior.

Alix Cléo Roubaud, Untitled (Correction de perspective dans ma chambre / Correction of perspective in my bedroom), 1980. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz.

Correction of perspective in my bedroom (1980), the series from which the exhibition takes its name, employs two negatives that are almost but not quite identical. They both show a naked Roubaud lying on her back on a wooden floor. In one, her face is in profile; in the other, she looks out at the viewer. Alternating and slightly layering them, the photographer creates a kind of stuttering self, revealing the subject to be inherently multiple and impossible to grasp from a single vantage. There is a staging of identity here that speaks to the performative aspect of Roubaud’s practice, echoing that of contemporaneous American image-makers Francesca Woodman and Duane Michals. The photograph is not the mere product of sight; it is the unfolding of an event that exceeds the limits of vision. Michals explains: “Everything can be photographed, most of all the difficult things in life: anxiety, the afflictions of childhood, desires, nightmares. The things we can’t see are the most meaningful. You can’t photograph them, merely suggest them.” This is precisely what Roubaud achieves in her manipulated pictures.

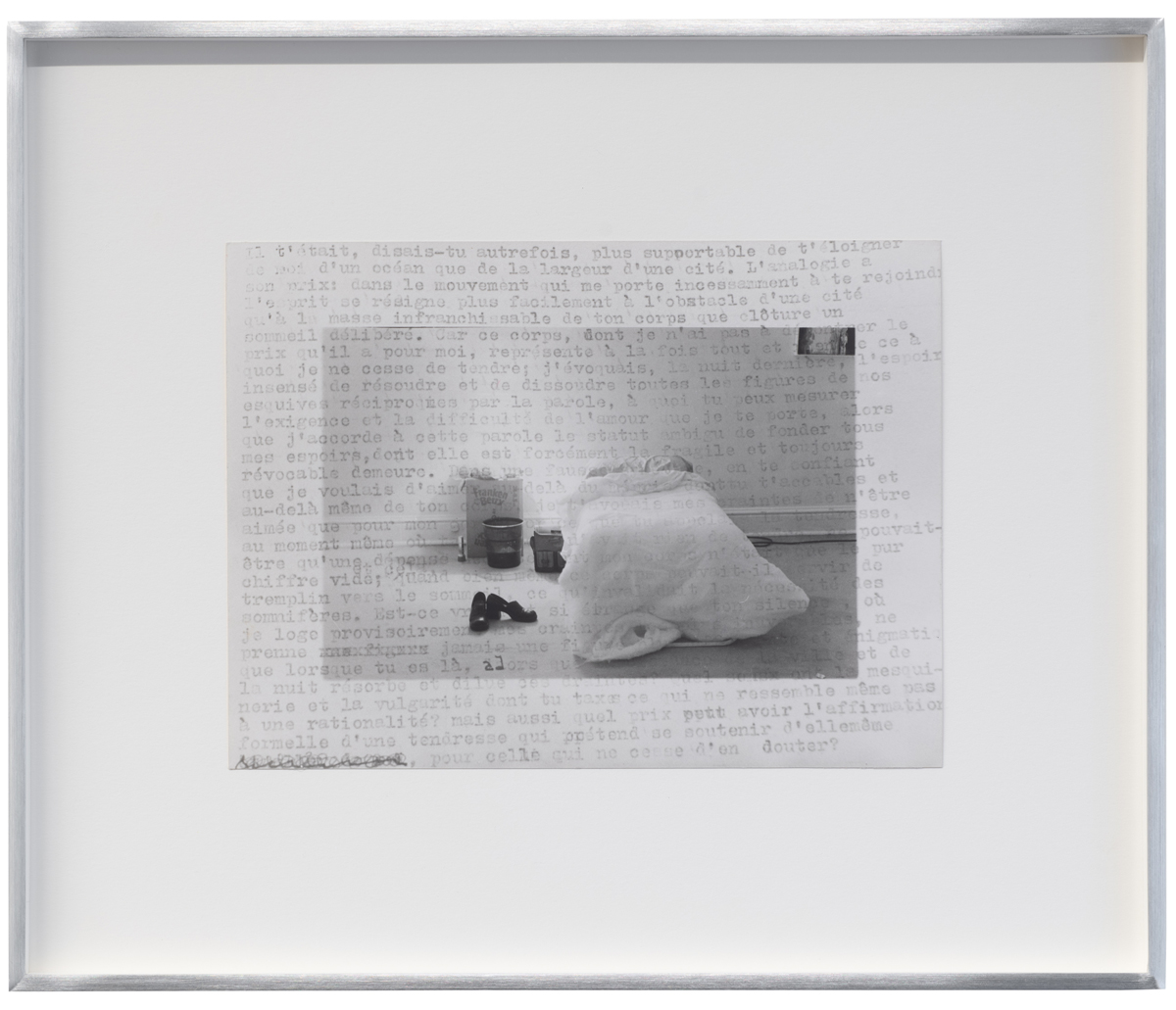

Alix Cléo Roubaud, La dernière chambre. / The last room. Ottawa 1973 Paris 1979, 1979. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz.

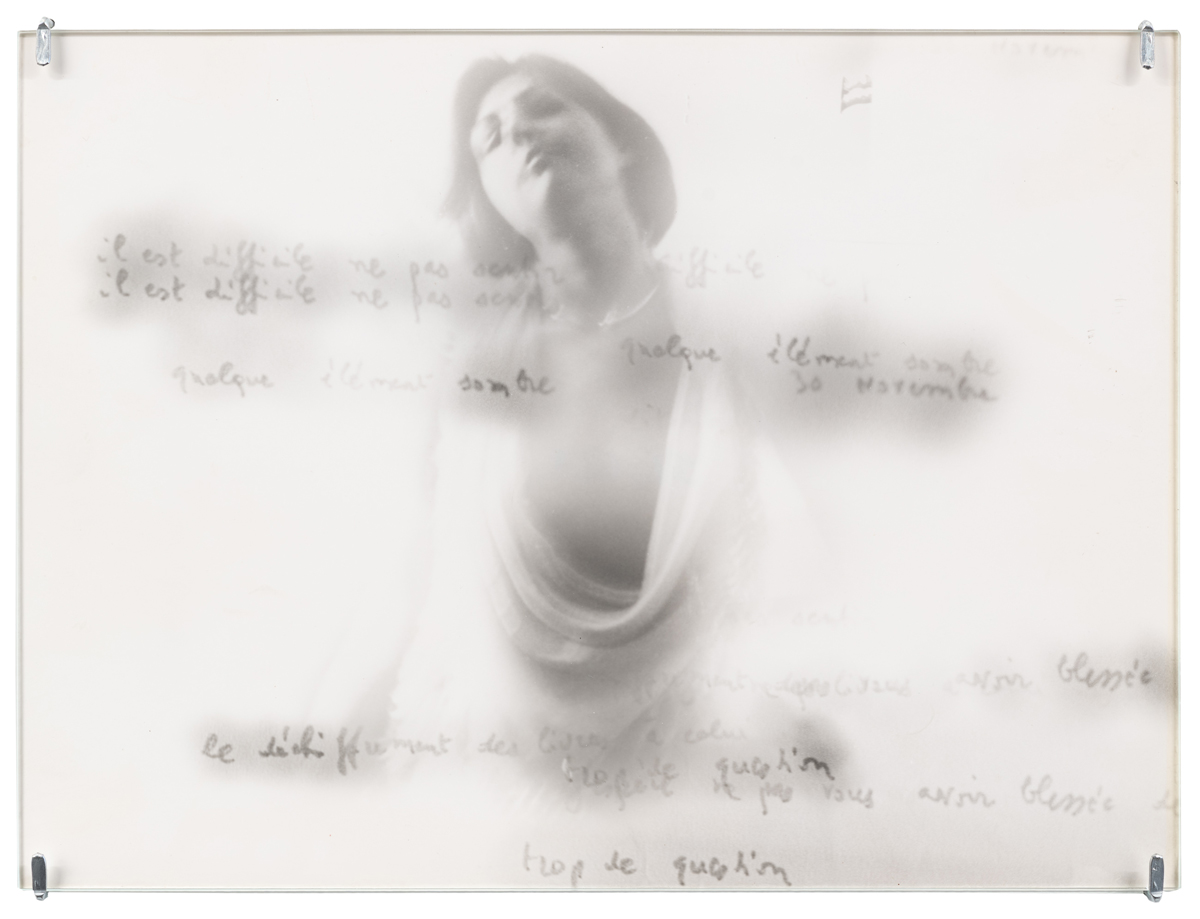

As in Michals’s work, a number of pieces in the show pierce the purity of the visual through the inclusion of text. In The last room (1979), a typed letter by the artist that laments to an unspecified lover the difficulties keeping them apart floats over the photo of an empty bed. In Untitled (ca. 1980–82), a fragment of an emotional missive from her husband is interwoven with the artist’s head and torso. Untitled (Protohaïkus) (ca. 1980–81) is centered around a poem of his. In all these cases, printed words function a little like voices do in the films of Marguerite Duras and Alain Resnais, which the photographer would likely have seen (Hiroshima Mon Amour comes particularly to mind). In them, a voice-over describes an event that took place in the past or in the space of imagination. Viewers are invited to assume that what they watch onscreen relates to the story being told, but in a way they can never fully determine. The same uncertainty infuses Rouboud’s image/text experiments, and, as in those movies, they are permeated by an atmosphere of absence and loss. The pictures tantalize but elude access.

Alix Cléo Roubaud, Untitled, ca. 1980–82. Courtesy Galerie Buchholz.

Roubaud once wrote that the time of the photograph is the future anterior, “a paradoxical, melancholic conjunction indicating that which, in the future, is already finished,” as Giannecchini notes. “In Alix’s words: ‘when you see this, it will no longer be.’ ” But a trace remains, captured by the camera, then realized in the darkroom, an absent presence that Roubaud reveals by pushing the limits of her medium beyond the seen and into the conjured.

Margaret Sundell is editor-in-chief of 4Columns.