Jeanine Herman

Jeanine Herman

A pheasant for some quiet: Marcel Proust complains, politely, about noise.

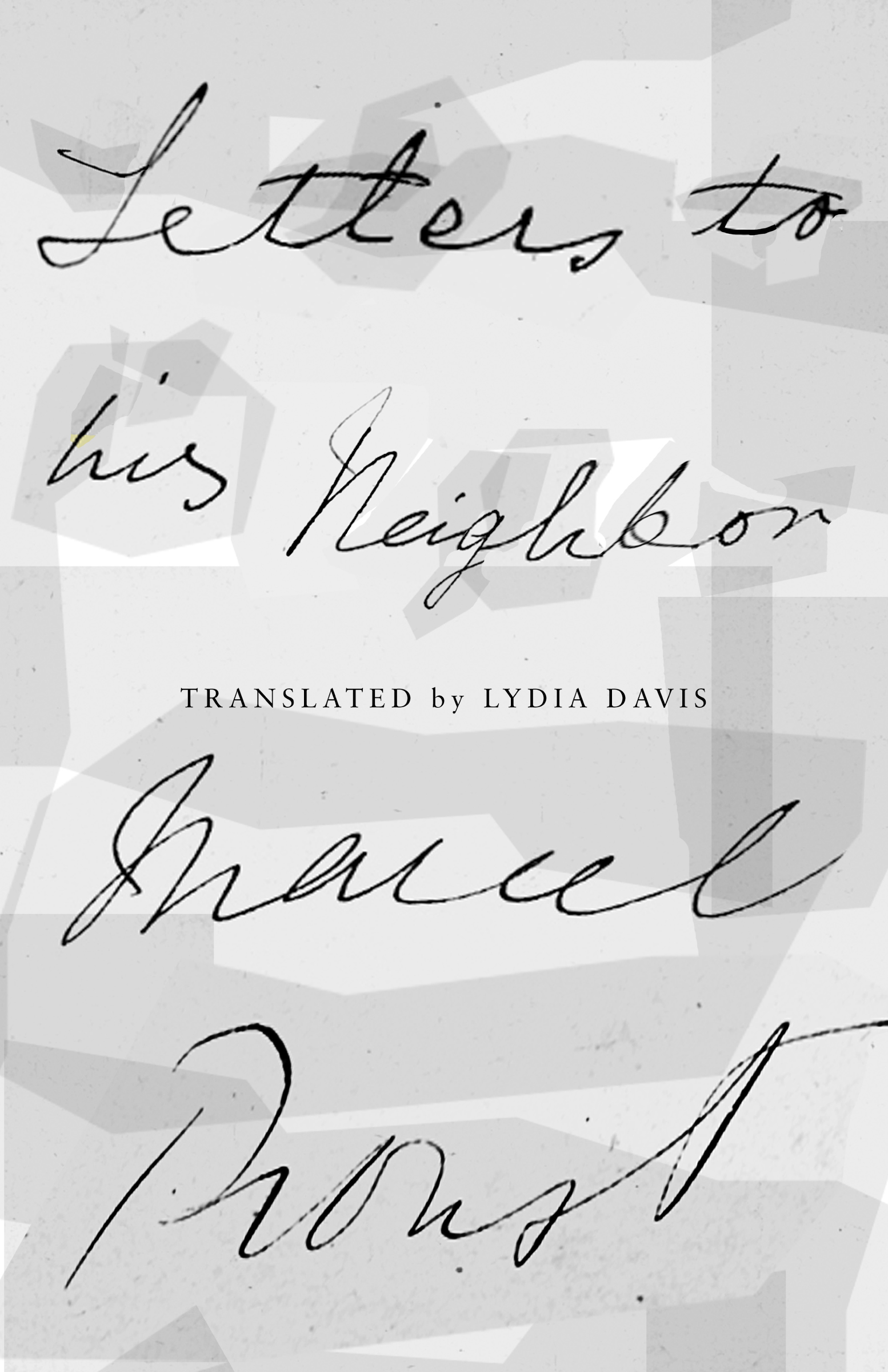

Letters to His Neighbor, by Marcel Proust, translated by Lydia Davis, New Directions, 110 pages, $19.95

• • •

“These days a plumber has been coming every morning from 7 to 9; this is no doubt the time he had chosen. I cannot say that in this my preferences agree with his!”

This lament, from letter 4 in this sad/funny book of letters from Marcel Proust to his neighbor, should resonate with any city dweller who has ever been subjected to noise from without and despair from within. It’s something to contend with, and some do it better than others. (As we speak, someone is sawing metal in the courtyard. Au secours!)

Proust’s neighbor, Madame Williams, is the recipient of these gently pleading missives. A Frenchwoman married to an American, she is cultivated, a little flirtatious. She is fancy—“very distinguished, very perfumed,” as Céleste, Proust’s housekeeper, puts it; she plays the harp and reads but also seems restless. Marcel and Mme Williams appear to have a real kinship, based on unspoken tristesse.

• • •

Embedded in compliments and embroidered with politesse, Proust’s complaints are never hostile.

Letter 22: “This one is just a quick note from a neighbor . . . in the little courtyard adjoining my room they beat the carpets from your apartment, with an extreme violence. May I ask for grace tomorrow?”

And in one of the occasional letters to Mr. Williams: “if in the morning there is hammering above me it’s all over for the whole day . . . Please accept, Monsieur, the expression of my highest regards.”

He sends the Williamses flowers; he implores them to keep it down but does so with pleasantries and pheasants. Even while lodging his complaints, Proust manages to sustain this elevated aesthetic. He remains meticulous and articulate in all things, though he does ignore punctuation.

• • •

I imagine someone discovering these letters and wondering where to put them—too quirky, too crazy, too minor, too marginal. But, as we all know, it’s the minor and marginal that are often the most interesting. And here the marginalia—the addenda and notes—are as essential as the letters. The foreword by Proust scholar Jean-Yves Tadié and the afterword by celebrated French translator Lydia Davis serve as codes to these letters, through which we catch a glimpse of the writer’s idiosyncratic domestic life:

Proust’s dining room, which became a sort of storeroom, contained so much old furniture—so much impedimenta, things he’d inherited that he couldn’t get rid of, holding onto them the way one does when one is attached to the past, when one is a passéiste (someone addicted to the past, who amasses things as a way not to lose anything else)—that the room, according to Céleste, was “like a forest.”

Proust appeared to enjoy some kind of incense or aromatherapy. Mention is made of mysterious powders being burned in his den of cork, powders he burned so frequently that his neighbors complained.

Proust was a night owl who prepared for the day at nine in the evening, with coffee and a croissant.

Proust would also sometimes summon Céleste in the middle of the night, to stand at the foot of his bed and listen to his problems . . .

• • •

He looks forward to the day when he will miss the noise, “mourning the vanished electricians and the departed carpet-layer” (because we miss everything eventually, even the terrible things, apparently).

He can imagine missing it. But for now, he’s burning his powders and metaphorically fanning himself. He is suffering!

See, in particular, this complaint about crates: “I have learned that the Doctor is leaving Paris the day after tomorrow and can imagine all that this implies for tomorrow concerning the ‘nailing’ of crates. Would it be possible either to nail the crates this evening, or else not to nail them tomorrow until starting at 4 or 5 o’clock in the afternoon . . .”

This note contains all of the pathos of feeling at the mercy of one’s neighbors, its specificity, its agitation, its deliberate formality. The “nailing” of crates is placed in quotation marks, because that’s what you do with things you can’t bear to acknowledge as real, things you want to pretend don’t exist.

I sympathize with Proust. I don’t think of him as a noise-phobic or neurotic so much as a writer with terrible soundproofing and too much construction work around him. I feel bad for him. What is to be done? Denial, rose-colored glasses, powder burning, the summoning of Céleste, and the occassional writing of letters to his neighbors.

• • •

Both Tadié and Davis mention the same letter—letter 25, about the destruction of Notre-Dame de Reims, a cathedral much beloved by Proust. Statuary is typically the first to go. But here amid the collapsing arches, sculptures of angels still collect fruit from “the lush stylized foliage of the forest of stones.”

It is World War I, Franz Ferdinand has been assassinated, things are being destroyed. People are dying around them—it isn’t just Proust’s ailments, neuroses, or unspoken malaise; it’s actual war and bombing at this point; there is true sadness and trauma in the air. People have reason to be depressed.

When he writes the letter about the plumber, it’s 1909, and summer; by letter 25, it’s the end of 1916. Mme Williams has lost her brother; Proust has lost his friend Fénélon. In letter 16, from March 1915, he speaks of “an experience of sadness that is already very old and almost uninterrupted.”

By letter 26: “Already I carry around with me in my mind so many dissolved deaths, that each new one causes supersaturation and crystallizes all my griefs into an infrangible block.”

The pretext of these letters may be noise, but the context is war, and the subtext is loss. Proust is seeking solace in the domestic and carrying on.

Jeanine Herman is the translator of ten works of fiction and nonfiction, including books by Julia Kristeva (The Sense and Nonsense of Revolt, Intimate Revolt, and Hatred and Forgiveness), Julien Gracq, Kettly Mars, Laure (Colette Peignot), and Nicolas Bourriaud. She is a Chevalier in the French Order of Arts and Letters.