Hermione Hoby

Hermione Hoby

Quiet intimacies commingle with the brutality of female grossness in a remarkable novel by the late author of Geek Love.

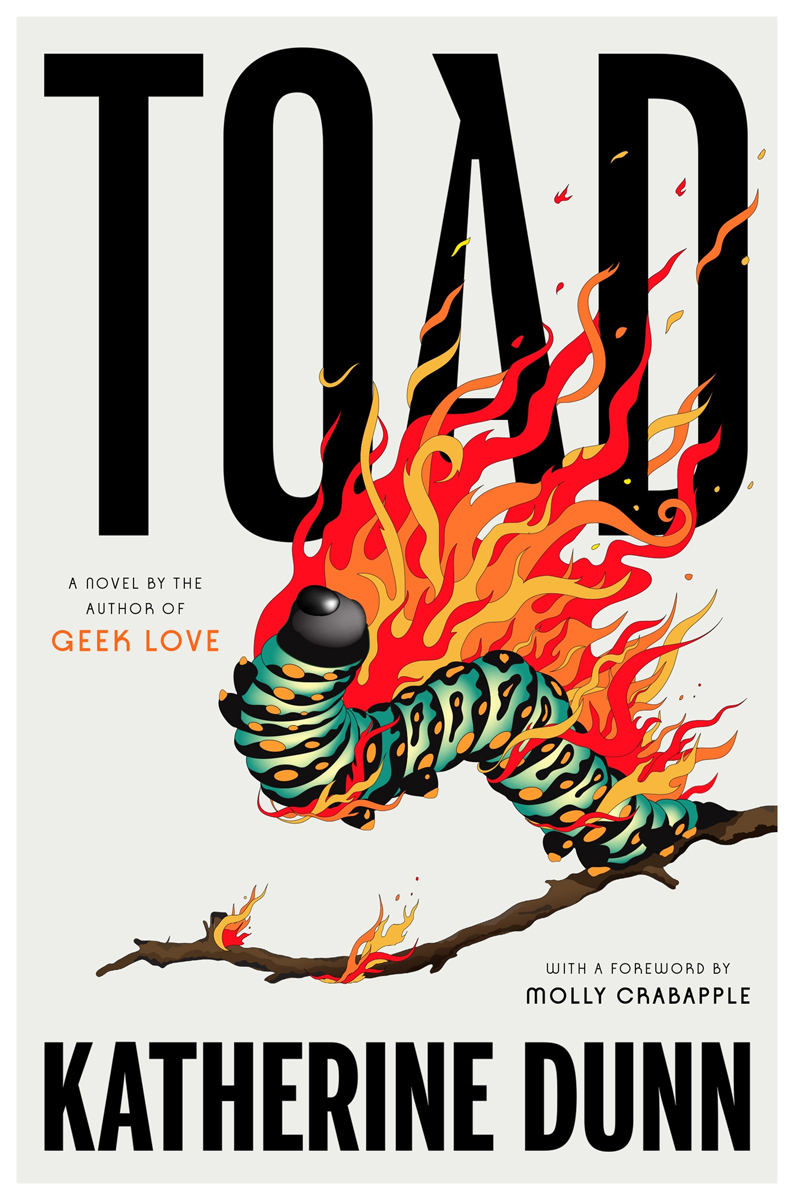

Toad, by Katherine Dunn, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 338 pages, $26.99

• • •

“Flowering” is too pretty a term for the phenomenon. What to call the current efflorescence of female grossness in fiction? Perhaps what we’re looking at is a kind of collective dirty protest: in many notable new women-authored novels, rage and disgust come locked in sustaining union—to be enraged is to be disgusted, is to wish to disgust, and so on. As the walls of decency are daubed with various fuck-yous of bodily fluids, a whiff of feminism arises.

One exemplar of the Extremely Loud and Incredibly Gross is Christine Smallwood’s very smart The Life of the Mind (2021), a novel which signals the ironic nature of its title with its egregiously bodily opening words: “Dorothy was taking a shit at the library when her therapist called . . .” There follows a meticulous description of another bodily event, the protagonist’s miscarriage, which arrives in “thick, curdled knots of string, gelatinous in substance.” The narrator of Claire Louise Bennett’s torrid yet nimble Checkout 19 (also 2021) is similarly fascinated by her own bleeding; indeed, “more than once” she has imagined taking some bloodstained menstrual tissue up to a makeup counter and asking for a lipstick “at long last in this most perfect shade of red.” And then there’s the scarifying Ottessa Moshfegh, whom critic Andrea Long Chu, in a review of this summer’s Lapvona for Vulture, anointed as “the leading coprophage of American letters.” (Unlike the benighted serfs of her most recent novel, I doubt Moshfegh herself eats actual dung: “coprophile,” then, might be the more accurate term.)

The finest new addition to this corporeal corpus is not actually new at all. Written in the 1970s, the decade of Roe v. Wade, and unpublished in the author’s lifetime, Katherine Dunn’s Toad is a remarkable, disquieting, and judiciously revolting posthumous novel about, among other things, unrequited love. Dunn, who died in 2016, is best remembered for her baggy, bravura Geek Love (1989), which follows the spectacular and improbable rise and fall of the Binewski family of circus freaks. The novel’s outsize quality—its gleeful, unrelenting mode of grotesque—can make a reader feel captive to some hyper-imaginative and precocious child gabbling out an outlandish story. You may be entertained, but it’s hard to believe a word. Toad succeeds not by being incredible, but by being so credible. It is, definitively, a novel for grown-ups, not just because of the advanced age of its narrator—the ornery Sally Gunnar—but because a thrilling, subtle, and wholly persuasive adult anger animates the book. I believed every word.

It begins in the present of Sally’s dotage, with her living in a bungalow, alone but for some goldfish and a “scarred old toad.” Pages in, she announces that her life “is clean now”—the phrase hints darkly at the soon-to-be-revealed filth of her youth. When her visiting sister-in-law mentions a certain “Sam and Carlotta,” the mere utterance undoes her—“slits me neatly from skull to crotch and leaves my two spread halves gaping bloodily at the fish.” The story then caroms backward, to Portland, Oregon, and the late-’60s squalor of student days.

Despite its jumbled chronology, Toad tells a brutally straightforward story, namely of the charismatic young couple’s doomed relationship, as recalled by Sally, a suffering bystander. Sam is an unwashed yet affable dilettante who lives in a cat shit–encrusted hovel (the stuff “lay in thin, stiff smears on the carpets”), where he subsists on charred horsemeat, philosophy, and his own sense of entitlement. He is studying (ostensibly) at “the local prestige college”—unnamed but identifiable as Reed College—where Sally, crucially, is not. Lacking family money, she instead works as a waitress at a coffeehouse, and her stomach churns “at the sight of the other girls moving across the green campus. Their lives seemed so calm and ordered, directed and productive.” Sally’s class-conscious eye soon finds a near-permanent object of envy in Carlotta, whom she first spots dancing at a party:

She was all high arches and soft pink heels. Her toes were rosy and clean. She bent a knee and swayed, lifted one foot at a right angle to the other and gently, precisely, set her glowing toes down on a tight little roll of dog shit. She lifted the foot casually, danced out of the dirt and into the long grass. She continued to sway her arms, although now she writhed and twisted as she scraped her toes through grass.

The implication is clear: to be successfully feminine is to be nice and unsoiled, to have rosy toes, and to discreetly, even artfully, wipe off any mess that comes your way. It is also to exist as something to be looked at. Gazing, grinning Sam instantly falls for the beautiful dancing Carlotta. “It’s a terrible thing,” Sally tells us from her vantage of decades, “to be a natural-born buddy, a pal, a sympathetic face peering over the top of a glass, there to be wounded or cheered by others.” Her response to the injustice of being an unbeautiful woman in a sexual economy prizing pristine prettiness is buttoned-up rancor. In her mid-thirties, however, she finally cracks. After being abandoned by a lover apparently repelled by her neediness and physical bulk (his parting gesture is to urinate all over her stash of donuts) she runs naked, “thighs and buttocks clapping merrily together,” out onto Boston streets. A car will be pissed on, a shop window will be smashed, a man’s fingers will be severed, donuts will be regurgitated on a hospital floor, and Sally, finally, will be committed to a psychiatric institution.

It’s one kind of terrible thing to be a natural-born buddy. It is, however, a different kind of terrible thing to be a natural-born dream girl. The former gets overlooked, the latter overly looked at. Much of the novel’s heat comes from the complexity of Sally’s feelings toward Carlotta; beneath the bite and verve of its prose, Toad is attuned to the quietly tectonic nature of intimate relations, and things between these frenemies shift in strata and run deep. Memory’s restitution of Carlotta as a living person (“It’s a relief for me,” Sally admits, “. . . to remember these scenes . . .”) dispels callow spite, and as the book proceeds, Sam’s hippie-babe cum homesteading baby-mama emerges into three-dimensionality, no longer just a set of rosy toes nor merely the love object of Sally’s own love object.

And then comes Carlotta’s madness. (Even dream girls get the blues.) When a specific tragedy strikes, one we receive as a distillation of the book’s ambient tragedy of male fecklessness, it drives her into a bloodlusting, disfiguring rage of Euripidean intensity. Earlier, Sally had asked Carlotta what it was like to give birth. The new mother answers with “tremoring hands”: “It’s like taking a big shit. That’s really what it feels like.” And with that, Dunn strides up to the altar of motherhood and craps all over its lie of sanctity.

Dunn has desecrated rosy childbirth myths since her debut, Attic, in which an old woman pulls a fetus out of a younger woman’s body and eats it. Attic was published three years before the first Roe v. Wade decision; Toad was written four years after. What a peculiar experience it is, then, both galling and gratifying, to read this book decades later, now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned. It’s not that Toad is exactly prescient—assaults on female autonomy are of course ongoing (the galling part), and concomitant female rage remains their warranted result (which explains much of what is gratifying.) But I wonder if Dunn had any idea how much her strange, savage, tender book would come to be protesting.

Hermione Hoby is the author of the novels Neon in Daylight and Virtue. Her criticism has appeared in Harper’s, the New Yorker’s Page-Turner, the New York Times, the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, frieze, and elsewhere.