Yasmine Seale

Yasmine Seale

In Colette’s duo of novels, the duel of lovers.

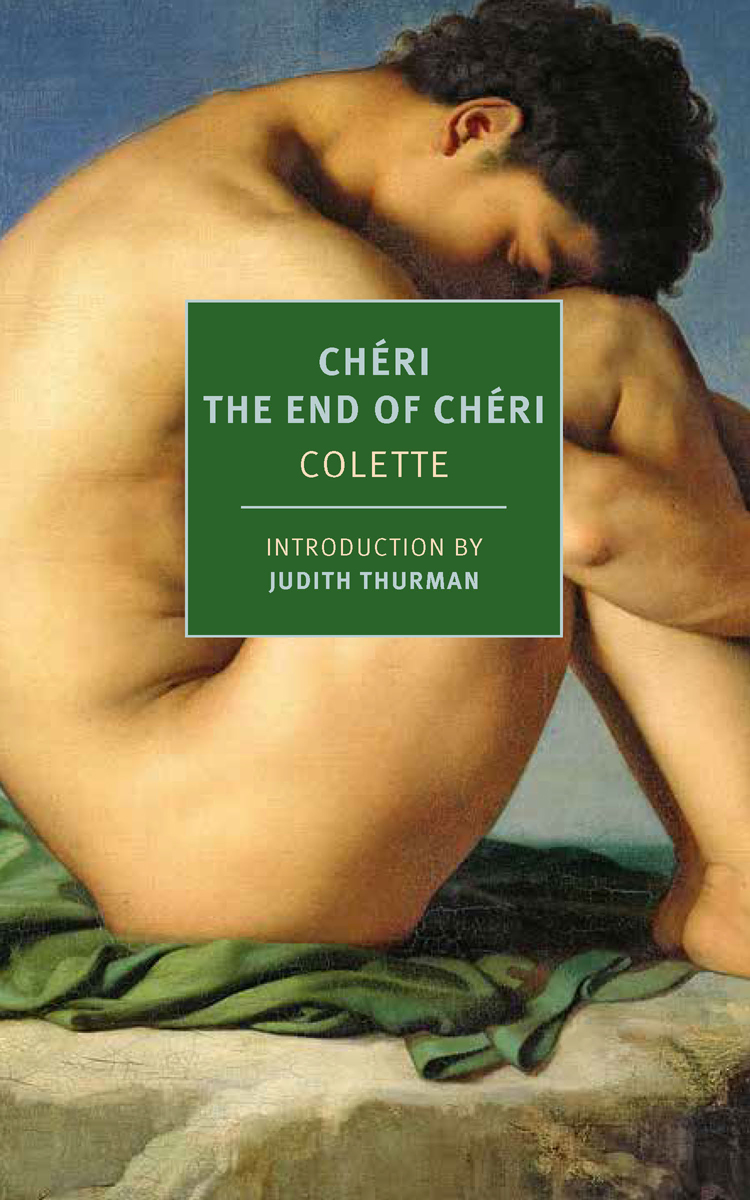

Chéri and The End of Chéri, by Colette, translated by Paul Eprile, New York Review Books, 237 pages, $16.95

• • •

Love is central to all Colette’s mature fiction. To her second husband of three, this seemed a waste of her talent. “Aren’t there other things,” he griped, “in life?” A political journalist and editor of some of her most brilliant reportage, he urged her to look outside the bedroom window. (An improvement on the first husband, who made her pen a series of autobiographical novels, published them under his own name, and pocketed the handsome proceeds. The third, bless his soul, let her be.)

“But what are politics?” writes Judith Thurman in her preface to Paul Eprile’s new translation of the Chéri novels, Colette’s brace of masterpieces on the end of an affair. “A devious scrimmage for the upper hand.” Written either side of the second divorce and set either side of the First World War, they are a study of relationships as a species of trench warfare, establishing their author as the Clausewitz of the world behind closed doors. Chéri (1920) begins in the battlefield of a rose-colored boudoir; a wrought-iron bed shines “in the darkness like armor.” Léa de Lonval, wealthy courtesan, is tussling over a pearl necklace with her lover Fred Peloux, known as Chéri, a gorgeous, fatherless hedonist half her age. After a six-year idyll—she sometimes calls it “an adoption”—they are at a threshold they don’t yet know they fear: Léa of the change of life, Chéri of life itself. His hair is “tinged with blue like the plumage of a blackbird.” He will soon marry, leave this nest. The forty-nine hard pearls at Léa’s throat, a clue to her well-guarded age, expose the slackening muscles beneath. Seduction is exhausting, cruel—but does she have “the courage to know when to quit”? The novel glides between opulent rooms; doorways and mirrors structure its concern with what lurks over the rim.

Chéri is the son of another retired cocotte, a woman who “never repeated a truism less than twice” and who Léa, preferring this to silence, spends much of her time out of bed with. Behind the central romance is a coruscating portrait of this fellowship of rivals, “lying in wait for the first wrinkle and the first gray hair.” Here is Madame Peloux telling her best friend she smells good: “Have you noticed, when your skin starts to sag, perfume soaks in better?” And you haven’t heard her thoughts; she fantasizes about bleeding Léa’s firmer neck “to tint the slender greenish lily pink.” Necks—“grainy,” “corrugated,” “flowerpot-shaped”—are the only straight talkers in the book.

Colette writes like a fencer, in controlled, impressionistic sallies. This is also how her characters behave, in vignettes so rich with barbed observation it is easy to forget how little they do with their days. There is less intrigue in some parliaments than in the games of piquet where Léa and her hangers-on privately assassinate each other behind masks of simpering benevolence. The lovers are too busy parrying to notice they’re bleeding. They regulate their breathing so as never to be caught off guard, inspect each other through falsely drowsy eyes, size “each other up as opponents” after kissing, and are finally horrified to discover that, despite their precautions, they are in love. But it is too late. Léa lets go of Chéri and, from the window, watches him lift “his head up to the spring sky and the chestnut trees loaded with blossoms . . . filling his lungs with air like an escapee.”

It’s bewildering outside the nest; no rebirth comes. The End of Chéri (1926) finds our hero returned from the front with a medal for bravery acquired by dumb luck, less shell-shocked by the war than by the hectic années folles taking its place. The professional parasite he used to lunch away the days with, tearing “into peacetime with the fury of a warrior,” now runs a dance hall where “the telephone gleamed like a weapon in daily use.” Chéri’s mother has become a speculator in real estate; his wife, Edmée, when she isn’t investing his inheritance for him, manages a clinic for injured soldiers and is aghast when he suggests they have a child. Wondering where he fits in, he visits Léa, now nearing sixty, and finds a “serene disaster”: a large, jovial woman who no longer wants to flirt or parry. The pearls haven’t changed, and neither has Chéri. Out of step with the striving world, sick with nostalgia for the sheltered, almost uterine innocence of his belle-époque boyhood, he shoots himself in a room plastered with pictures of a younger, corseted and powdered Léa.

Cause of death? Women’s emancipation. Colette, full of scorn for suffragettes, ran counter to her own day’s feminism—never mind today’s. She believed in skirting the system, not reforming it. Yet perhaps the distant dream of equal rights (women in France were legal minors until 1938) was less remote to Colette than the very notion of a woman being vulnerable. In her fiction’s demimonde, the necessity of making one’s own rules paradoxically tips the balance of power in favor of those dealt the weaker hand; Edmée, at nineteen, already displays “a prisoner’s easy employment of dodges and wiles.”

Eprile’s exquisite translation catches the glint, now songlike and now savage, of Colette’s sentences, her dialogues filed to a point. It is in that spirit—and to draw out how rich, how pearl-like, her prose is—that I want to linger on a line Thurman, after giving us the French, picks out for praise. Chéri is leaving Léa’s flat for the last time. “Il remarqua que le ciel rose se mirait dans le ruisseau . . .” “He did notice that the pink sky was being reflected by the stream in the gutter . . .” Colette’s clause ends on a word that can refer either to wastewater or to a babbling brook; on the first morning of the rest of his life, Chéri is caught between the pastoral Eden he is leaving and the squalor of the urban real. “In the gutter” allows only for the latter.

Nor is this the first suggestive image in the sentence. Se mirer, Colette’s verb, has a grand, perfumed, slightly archaic flavor. It is the action of Narcissus in the pond, of a creature of leisure at her dressing table. “Was being reflected,” though accurate, unweaves the rainbow. Early in the first book, Léa picks up a mirror and finds fault with her “high complexion.” Now, at the end of The End, that scene is magnified as the dawn itself becomes a grande horizontale bending to inspect her flushed cheeks in the water, and (the sentence continues) in the blue feathers of low-flying swallows, which echo our first sight of Chéri’s plumage. We are back in the rose-colored room, with the roof blown off and Léa taking leave, ascending to some higher sphere.

Splitting hairs? Perhaps. Like rivalry, like love, these novels encourage a demented, uncharitable attention to the smallest things; they describe people on whom nothing is lost and seem to reward their vigilance. Chéri, endowed with a “feral refinement of perception,” decodes a tryst in a dark wood by the sound of belt buckles alone, and Edmée tracks his moods by the way he slips in and out of the intimate form of address. Desire makes close readers of us all.

Yasmine Seale lives in Paris, where she is a fellow at the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination.