Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

In the jazz musician’s autobiography, an elaborate, dizzying accumulation of memories and moves, tour stories and sonic endurance.

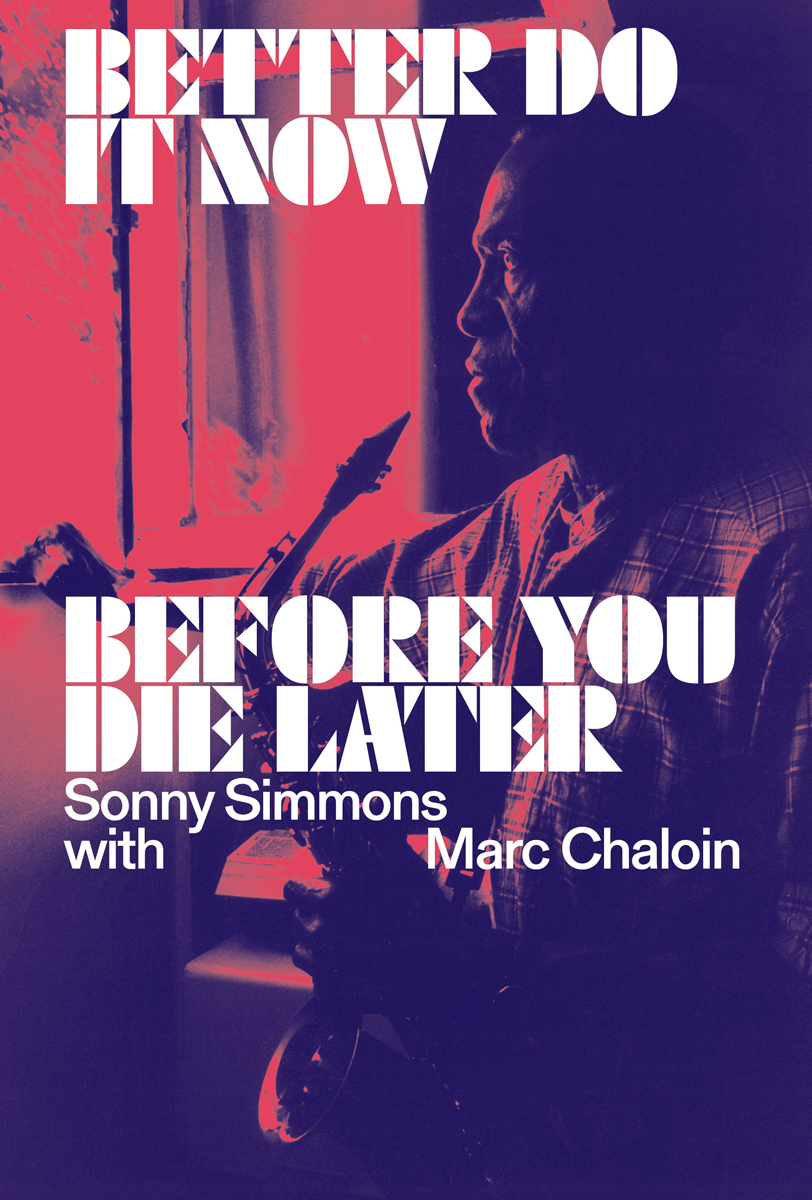

Better Do it Now Before You Die Later, by Sonny Simmons with Marc Chaloin, Blank Forms Editions, 553 pages, $45

• • •

The autobiographies of jazz musicians are their own siloed literary category, as the musicians themselves belong to an archetype that cannot be fabricated in fiction or imitated by wannabe bohemians; their ability to combine discipline and obsession with recklessness and self-destruction exists almost nowhere else in culture. In the case of Sonny Simmons, born in Sicily Island, Louisiana, in the summer of 1933, the eldest son of a preacher father who moved the family to Oakland when Sonny was a kid, his dictated and transcribed memories populate a new five-hundred-page biography, Better Do it Now Before You Die Later, so detailed and hyper-fixated on musical affiliations it’s part encyclopedia of black sound from the 1940s to ’90s. With the help of Marc Chaloin, the tales are organized chronologically, but you do get the sense Simmons has total recall and could share incidents in any sequence, especially those from the years before he began using heroin.

He adored the South, but, like many black families, the Simmonses were pushed off their land by whites and coerced into cities. In Oakland, Sonny began his tenure in the public schools barefoot, was teased ruthlessly for being country, and conformed over time until he was hip and zooted, owner of a run-down alto he helped pay for by picking cotton with his father in the Central Valley. We move through the agony of his inability to play well, despite locking himself in his family’s bathroom trying and failing to imitate Charlie Parker, to his gaining traction, facility, steady gigs, and acclaim. His earliest paying gigs are in R & B bands where he is made to honk and repeat one wilding note for fanatics in the style of Big Jay McNeely. He does this so well he’s invited to tour; he’s around twenty at this time and green and grinning into the brass and sending money home to his parents via post or Western Union. On the road he’s mocked for refusing the groupies who come to his door as if obeying some divine calling to distract and seduce him. Instead, he barricades himself in his hotel room and practices, just like at home. Simmons blurs virtue and solipsism in his accounts; he’s well-behaved because he’s disregarding anything that won’t advance him musically or help provide for his family. And he’s volatile about his restraint. If his regime is interrupted, he seems ready to pull out the knife he carries or his mother’s .38 in retaliation against even a minor menace.

Sonny relays his escapades with an underdog’s humility but the blunt assuredness of a man of unwavering faith. He believes in God—and Charlie Parker, then James Moody, then John Coltrane and Billie Holiday, are God. He’s animated with a boyish conviction about black sonic beauty and endurance, and a sage’s indifference to anyone who disagrees. Because the book is written as if Sonny is testifying directly to us, we become firsthand witnesses to the fanatical enthusiasm of a man just as mesmerized and traumatized by the events he’s conveying now as when they occurred decades earlier. When back from his first tour, a cousin he didn’t know he had who also plays saxophone convinces Sonny to help him move heroin. He runs the drug but doesn’t try it then, and quits the job right before the operation is raided and his cousin sent to prison. He records one of his most celebrated albums, The Cry, shortly after the brutal death of his mother, who succumbs to injuries that could have been prevented had she not been denied adequate medical care at Bay Area hospitals, a Bessie Smith story. It’s 1962, pre–Civil Rights Act, and even in California segregation is customary and sometimes fatal. The album gets its title from the fact that Sonny would step out of the recording session sobbing between takes. This is the last mention of his parents or immediate family in the book. It’s as if once she’s gone, he becomes an orphan.

Or maybe she went away to become the angel he would need in the impending lean years. For a while, a growing reputation and a move to New York to flex it sustain Simmons. He meets and befriends heroes of his, like John Coltrane, who gives him money unprompted on their last encounter outside of one of ’Trane’s gigs, and Eric Dolphy, whose sheet music Simmons discovers strewn in the street, ejected from the loft Dolphy kept in Manhattan by factory-minded landlords, after his death in 1964. I briefly question Sonny’s memory in protest of the devastating mimesis that is this scene. There’s a cinematic record of Mingus watching the same cruel discard of his own sheet music. Is Sonny conflating the two events, or was this style of exquisite dismissal as common for jazzmen as a nightly woodshed? The errancy is dizzying. Sonny is these sheets in the wind, everywhere and nowhere, famous and unknown, a family man and a degenerate, erratic and steady, in the in-crowd and exiled, unmoored, to hear him tell it. It’s not until Simmons is forced by circumstance (a wife and a kid) to get a day job and retreat from the club scene that we see him resort to drinking and narcotics for solace, a pivot from which he never fully recovers, as if the horse were plotting and waiting for the opportune moment to make him ride, waiting until he was despondent and vulnerable enough to ride forever. He begins busking and begging, playing in the streets of SF’s financial district with frostbitten fingers in hopes of scoring, goes to prison for a year when caught with heroin, his wife leaves him taking their two kids with her, runs away with a drummer, and he maintains an affair with a woman he clunkily calls Lady X, and then another with a woman named Geraldine, who helps him settle in Paris for a while.

What starts out charming and in the elevated colloquial style of autobiographies by Miles Davis, Mingus, and Hampton Hawes, and goes on that way for the first three hundred pages, slouches into an elaborate litany of gigs, catastrophes, and moves from coast to continent to coast, many of the maneuvers more utilitarian than harrowing. What Sonny omits or glosses over creates tension and uneasiness in the story, an overriding existential nausea. He’s excessively candid about some specifics and too aloof about others; we accumulate too many scenes and not enough narrative and begin to feel complicit in talking over the heart of the matter, rambling as a form of delayed collapse or rage-abatement, the miscellaneous (his admission of some of his memories post-heroin) acrobatics of crows and recovering addicts. Tour stories descend into caravans of hearses, he has a gorgeous epiphany and names the saxophone a “reed-piano,” retheorizing its range, and he musters coherent disses at the ascendant generation, “The new thing is you get a horn and you scream and you’ll be a star.” He warns that to play “out,” you need a center, a sun around which to orbit, technique, otherwise you’re just tantrumming and bypassing real depth and skill. And you can feel the tantrum he’s withholding, wedged between memories, notes, and didactics. Of his time as a quiet member of the Black Panther party, he recounts: “I wish it had turned into a bloody massacre of the high bureaucracy that was controlling all the bullshit and handing down nothing to the black folks in America.” Sonny gets blue. He is too dedicated to give up, but too decent to give in to gratuitous celebrity-making or pimping and dealing; his are the unabridged misadventures of a middleman who deserves but distrusts the center.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa came out in April 2022, and the extended UK edition was released April 2025. Her book Life of the Party will be out this fall.