Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday

Nearly four decades after its release, relistening to the debut album that started it all.

Whitney Houston, by Whitney Houston, Legacy Recordings reissue

• • •

Recording artists who enter the industry prepared to be used by God, as messengers of the sacred, end up at the mercy of much more profane expectations. Whitney Houston, whose upbringing was rooted in gospel singing, hoped her faith would guard her on the road to fame. She possessed a combination of girl-next-door candor and impenetrable, regal reserve that allowed her to blurt out astonishing insights during interviews and then recede or detract from them with wit, elegance, and a nearly imperceptible quotient of self-abnegating humility. She often seemed nervous when speaking to journalists, like something she’d say might get her into trouble with the God she was there to serve, her own ego, her handlers, or the manifold tribunals disguised as fans. The most rending example of this timid idiom of hers occurs in 1993, when she explains to Barbara Walters, “I basically just wanted to be a background singer, I wanted to sing with my mother. That was safe for me.” For better or worse this kind of forfeiture is often prohibited by the unwritten but etched-in-blood laws of celebrity. You either become a legend or a disgrace. You don’t regain the privilege of anonymity once the spotlight has chased you onstage. Whitney Houston was anointed that way, and there would be no small-time fame in her destiny; her dream would have to expand with her role in popular culture. If it didn’t, she would be reconfigured by that culture until she resembled Western society’s distorted composite of a “star”—secular, sex-symbol-ready, and frivolous or callous enough to laugh off the invasive projections of a public.

The fate of this level of visibility and its accompanying fanaticism—enforced, offered, then mandated on the dotted line of a recording contract—is often tragedy in one form or another, mundane or severe. It’s hard to get over that and back to the music, as a listener. But let’s reflect on the joyful sounds and see if they survive or suffer these surrounding blows. On Valentine’s Day, 1985, after having been discovered by Clive Davis when he heard her sing a version of George Benson’s “The Greatest Love of All” that gave everyone in the room the chills, Whitney released her self-titled debut album, which will be the first in a series of reissues released this year by her estate. Hear “discovered” inflected with circumspection—her family and community already knew who she was and what she could do; she had been singing with her mother, Cissy Houston, who sang backup for stars like Elvis and Aretha Franklin, for several years. Her debut on Clive’s Arista label was the product of a yearlong development process, time spent courting producers and looking for the ideal songs to coalesce into a balance of up-tempos and ballads, singles that could stand alone, and substance. Whitney was being packaged for mass consumption. Her skill as a singer was almost a liability or distraction—she once insinuated she worried it might not fit the industry template, and you can hear the record’s attempt to downplay the sheer intensity of her gift with lightheartedness.

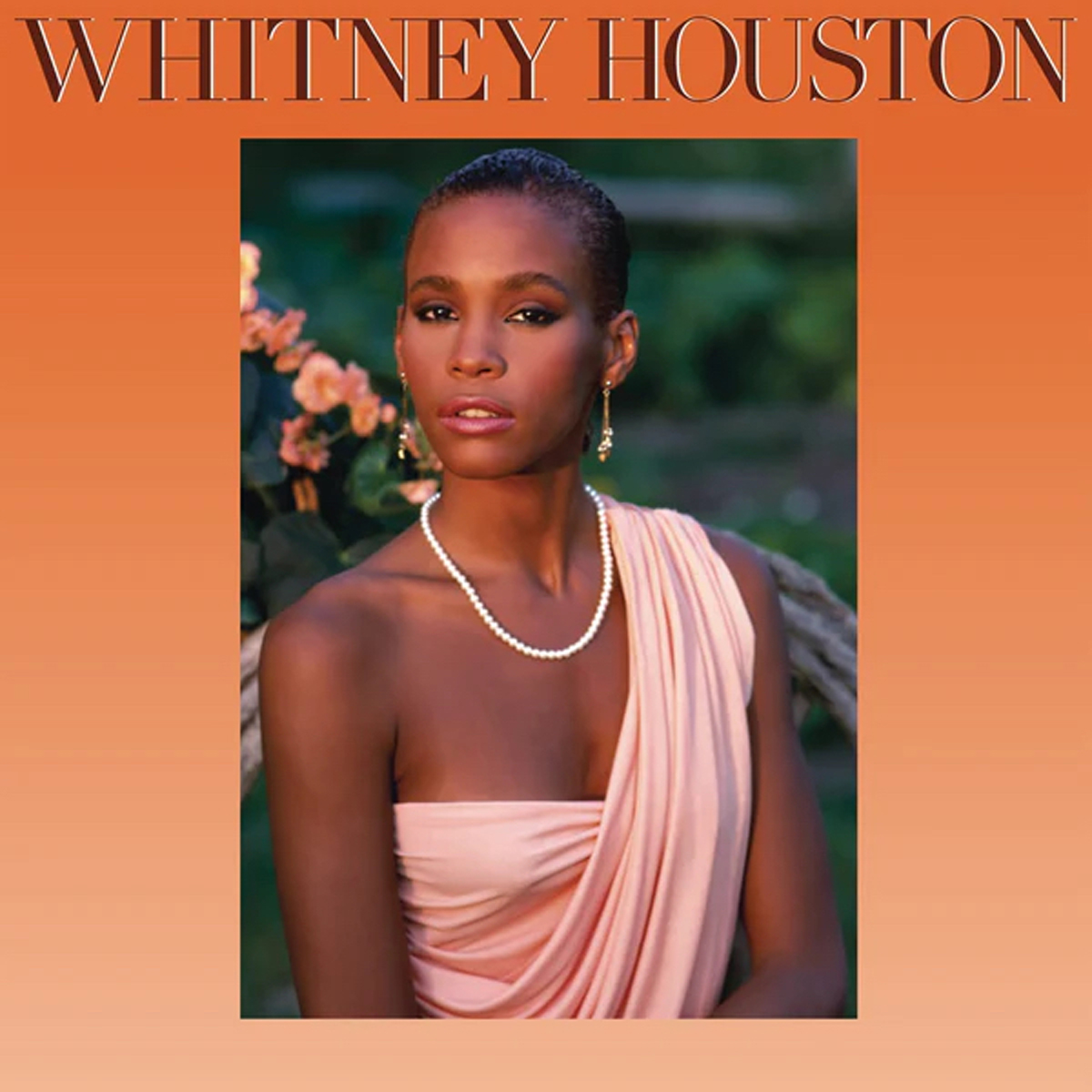

Since this is her debut, the texture of the cover is as important as the opening song, and it lives on as portent. She’s in a muted peach strapless gown, looking spartan, ethereal, and positioned somewhere between the Garden of Eden and one of those department store photo shoots that used to be all the rage at Sears and JCPenney. She offers the camera a hunter’s glance, layered with an edge of suspicion, as if she’s appraising as much as being appraised. And her posture is defensive, poised. The first track and first single, a celebratory ballad, “You Give Good Love,” is somewhat misplaced and awkward. Whoever the muse is, the singer, despite her effortless grasp of higher pitches, sounds mechanical and unconvincing. It’s because the song lacks an engaging story, and just repeats the title assertion into oblivion. We move on, to an up-tempo romance, a little more tortured, and a lot more charismatic, with a rubato hook that makes you wanna dance and sing along. Late at night, a rendezvous / being such a lovesick fool / it might be pouring rain. The lyrics are maudlin, but the groove overrides them, it’s sultry and whimsical, deep yet capricious in mood.

I can’t help but think to myself, this early in the relistening experience, that Whitney deserved better, and I spiral into an investigation of all of the ways the past is incriminating when we know the future. I’m distracted by that future, now also in the past, and having a quantum experience where time and space collapse into event horizon until I cannot locate the hedonism one needs to truly enjoy ’80s pop music. Repackaging her debut’s stammering exuberance to re-inflect her legacy with a lighter commercial resonance, somewhere between nostalgia and the resurrection fantasy already at play as “The Whitney Houston Hologram Tour,” seems like a futile declaration of love a little too late. Are we to gush over the music, or the fetishized posthumous wax figurings of Whitney that keep reprising? Should this album return as is, or would she want an album of unheard duets with her mother, or a gospel album, something more elemental? Either way the sound on this LP is more of its time than timeless. Whitney herself and her voice and her spirit are timeless, the way she stylizes overwrought songs to make them majestic is, and that’s still shape-shifting in her absence. However, the cloying pop love ballads and ’80s dance tracks with lukewarm or pedestrian arrangements reflect the regimented materialism of that decade. They don’t all translate, even as the star who is Whitney does. She outshines the material.

One standout track is the upbeat “Someone For Me,” which is bubbly and kinetic along with being lyrically agile. It possesses an addictive crescendoing hook that gives Whitney a chance to back and improvise with herself in yelps and runs both soulful and dazzling. The other is “Greatest Love of All,” a triumphant ballad that she rescues from an excess of sentimentality and turns into an artist’s statement in the middle of other people’s statements. Where many of the songs feel imposed upon her, these two belong to her alone. The booklet accompanying the reissue might be its value as merch, although I contest the leveraging of backstory and ephemera over vaulted sounds that would be new to us.

At Whitney’s funeral, Clive Davis gave a speech that’s moving or frightening depending on the mood you’re in when you hear it. He claimed that Whitney had told him of plans to get back in shape and ready for tour a week before she died, and then he looked up from his eulogy and declared, “I’m gonna hold you to it.” Maybe his eerie theatrics mirror the hold she has on all of us, and in turn we hold her to the stark innocence and meteoric ascent that this debut symbolizes. Whitney, who left us when she was just forty-eight, was already on her way back to God on this first album, pursuing her greatest love. God wanted her more, as she once said of another singer. She’s part of a long tradition, from John Coltrane to Prince, of black musicians who found ways to secularize their sounds but not their drives, whose statures were irreconcilable with an inner yearning for piety. From that perspective, this reissue is testament to a calling, full of light and haunted, that can only be answered and lived.

Harmony Holiday is the author of several collections of poetry and numerous essays on music and culture. Her collection Maafa came out in April, 2022.