Sowon Kwon

Sowon Kwon

At Marian Goodman Gallery, six works showcasing a decades-long interrogation of institutional inequities.

Andrea Fraser, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser. Pictured, center foreground: Um Monumento às Fantasias Descartadas (A Monument to Discarded Fantasies), 2003. On back walls: White People in West Africa, 1989/1991/1993.

Andrea Fraser, Marian Goodman Gallery, 24 West Fifty-Seventh Street, New York City, through February 25, 2023

• • •

An artist associated with the growingly historicized practice deemed “institutional critique” (alongside Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Hans Haacke, Louise Lawler, Christian Philipp Müller), Andrea Fraser has mounted her first exhibition with Marian Goodman Gallery. A survey of six select works, the show comprises photography, sculpture, text, and performance-based video that span from 1989 to 2022.

In the north gallery stands Um Monumento às Fantasias Descartadas (A Monument to Discarded Fantasies) (2003), a conical pile of colorful costumes near ceiling height. Collected on Rio streets after Carnival, the still-vibrant textiles and accessories have been wrested and “upcycled” into a sculptural ode. Are there costumes through and through, or is there a hidden structural armature underneath? The slope at which the cone rises would suggest the latter.

Andrea Fraser, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser. Pictured: Reporting from São Paulo, I’m from the United States, 1998.

Duly adjacent is Reporting from São Paulo, I’m from the United States (1998), a five-channel video installation of CRT monitors with chairs and headphones. As gifted a performer as she is a rigorous thinker and writer, Fraser takes up various guises throughout the show. Here, as an on-the-ground reporter at the 24th São Paulo Biennial, she conducts decidedly credible made-for-TV interviews (on anthropophagia/cannibalism, the biennial’s theme; art’s role in Brazil’s economic and global ambitions) with visitors, the chief curator, the cultural minister, and other officials of the international event. Demonstrating Fraser’s well-honed sense of the absurd, the broadcast footage includes interviews with herself as a participant-artist.

Andrea Fraser, Reporting from São Paulo, I'm from the United States, 1998 (still). Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. © Andrea Fraser.

Fraser is probably best known for her museum tours, in which she highlights and pushes up against (sometimes literally) august institutional norms. Welcome to the Wadsworth (1991) is performance documentation–cum–video installation in which a prim and professional Fraser walks viewers through the immediate exterior grounds of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. Characterized in the press release as an examination of “Yankee ethno-nationalism” and its connection to economic and racial segregation, the scripted performance draws from research on the city’s patrimonial heritage, sociological studies on urban blight, and the museum’s discourse. I chuckled at Fraser’s enumeration of portrait after portrait of progeny after progeny, of the “first families” memorialized at the museum, and marveled at her focus amid onlookers and passersby. “I deserve peace and tranquility after a full day. I want a serene and simple, a secure and stable life . . .” she recites as a hurried, gray-suited man walks past, almost as if voicing aloud his thought bubble. Fraser’s precocity, wit, fearlessness—it’s all there, if in slightly fuzzy SD-to-HD video conversion format.

Andrea Fraser, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser. Pictured: Welcome to the Wadsworth: A Museum Tour, 1991.

Exiting the viewing room from one guided tour, I noticed, among the eighty-two snapshots that make up White People in West Africa (1989/1991/1993), tourists on another. Many of the images in this series are mundane—folks dining at leisure, or at reception desks and poolside, mostly in Ghana—while some feel pointed, as when a Black figure is juxtaposed with a white elbow protruding from an ambulance window, or when Fraser is surrounded by Black children in a composition worthy of missionaries and UNICEF. The photographs wrap around three walls and a nook in a line, stopping midway on the largest wall, intimating an incomplete and ongoing process of repetition and circularity in colonial relations, a circle not yet closed.

Andrea Fraser, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser. Pictured: White People in West Africa, 1989/1991/1993 (detail).

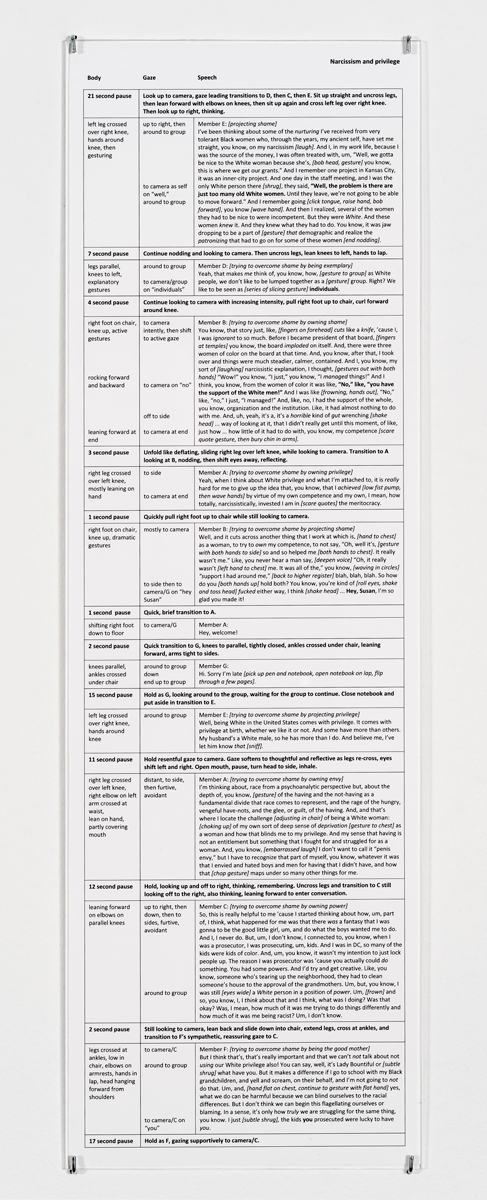

The exhibition is clearly designed to assert Fraser’s engagement with issues related to racism, colonialism, nationalism, and cultural appropriation as long-standing, culminating with This meeting is being recorded (2021). A single-channel video in the south gallery at the end of a long corridor, the installation also includes an editioned set of laser prints, This meeting is being recorded: Rehearsal script draft 11, table 8 (2021/22), on an opposing wall. Consisting of fifteen annotated “pages,” the prints vary in length and hang flush at the top, creating the effect of a rag at bottom. Seven participants are identified as A–G, and their body, gaze, and speech cues are delineated, as are organizing themes (among them, “Race versus gender”; “Defenses”; “Racialization of perpetrator and victim”; “In-group conflict”; “Vulnerability and rage”).

Andrea Fraser, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser. Pictured: This meeting is being recorded: Rehearsal script draft 11, table 8, 2021/2022.

The vertical-format rear-projection video features a seated Fraser channeling the “self-segregating” intergenerational white women who, we learn from the press release, put themselves “to the task of examining their internal racism and their roles in White supremacy.” Based on transcripts of six Zoom meetings convened in 2020, in which the women applied psychoanalytic group relations methods while sharing testimony, and completed in one ninety-nine-minute take, Fraser’s feat of memorization/enactment is nothing short of phenomenal. Weaving in and out of voices, postures, directed looks, and even tears, according to script, she inhabits all the participants, including herself. She hugs a knee as one, then smoothly leans forward with elbows on knees as another, or raises her intonation at the end of one sentence before resuming a lilting drawl; in effect, continuously “morphing.” Props are minimal—a small notebook and pen, a thermos, and a chair, from which Fraser performs directly to and for the camera at about 1:1 scale to live bodies. Six similar if not identical chairs are arranged on carpeting to form an open circle with the screen, as if inviting viewers to “join.”

Andrea Fraser, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser. Pictured: This meeting is being recorded, 2021.

Fraser’s eyeline meets ours often, and her mode of address shifts repeatedly to second person (“so when you, um, talk about those fears . . .” “you, you sound so resolved about that history . . .” “I really hope you stay so we can work on this . . .”), making it difficult to only eavesdrop on the intense self-disclosure and effortful communication. But what appeared as an attempt to engage the viewer in identificatory emotion, or discomfort if necessary, toward self-awareness, did not quite land for me. It took some staying, but when Fraser performing Fraser (most likely) observes that the recording is “the superego ear, you know, or eyes, it’s the judging gaze . . .” and later another participant confesses, “I felt judged” and “I feel disliked,” I realized what I felt was neither judged nor Judge (viewers are positioned as such with the camera’s POV), but potentially juror. And what I was responding to was less the appeal to emotion, but to something like duty. We know how we feel about jury duty, yes? Yet, in classic immigrant fashion, I also felt the weight and import of being entrusted with “serving” in peership, with listening to and considering the evidence.

Andrea Fraser, This meeting is being recorded: Rehearsal script draft 11, table 8, 2021/2022 (detail). Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser.

In relating This meeting to another artist friend, I was met with silence. A pregnant one signaling polite incredulity. I suspect her reaction aligns with those of many non-white (and some white) colleagues, and in her silence are questions: What is it to insist on the ethnicity of whiteness in an effort to decenter it, only to re-center it as content? Is there a crucial distinction between whiteness declared vs. undeclared, or can the self-reflexive declarations yield more business as usual at another level, in another guise? I do see poignancy in this bind, but also noted that the “Narcissism and privilege” page of the rehearsal script is the longest.

Is it inevitable that in exposing some structural conditions, others are newly obscured? Is naming enough, however cogently, exhaustively? Intellectualization can be a powerful avoidance and defense mechanism, after all, probably the slipperiest. How are big things continuously held up—be it a monumental cone; or, specific to the site of a commercial gallery, the murky workings of the art market; or, indeed, white supremacy? I believe it a testament to the probity and courage in Fraser’s work that it helps us to better recognize and describe some of our biggest stakes. But also to want to push further. As far and deep as we can bear.

Sowon Kwon is an artist and educator based in New York City. She is working on a new series of text-based animations that explore coincidence, polyvocality, and Cold War subjectivities.