Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

Stone work: when earth art hit the mails.

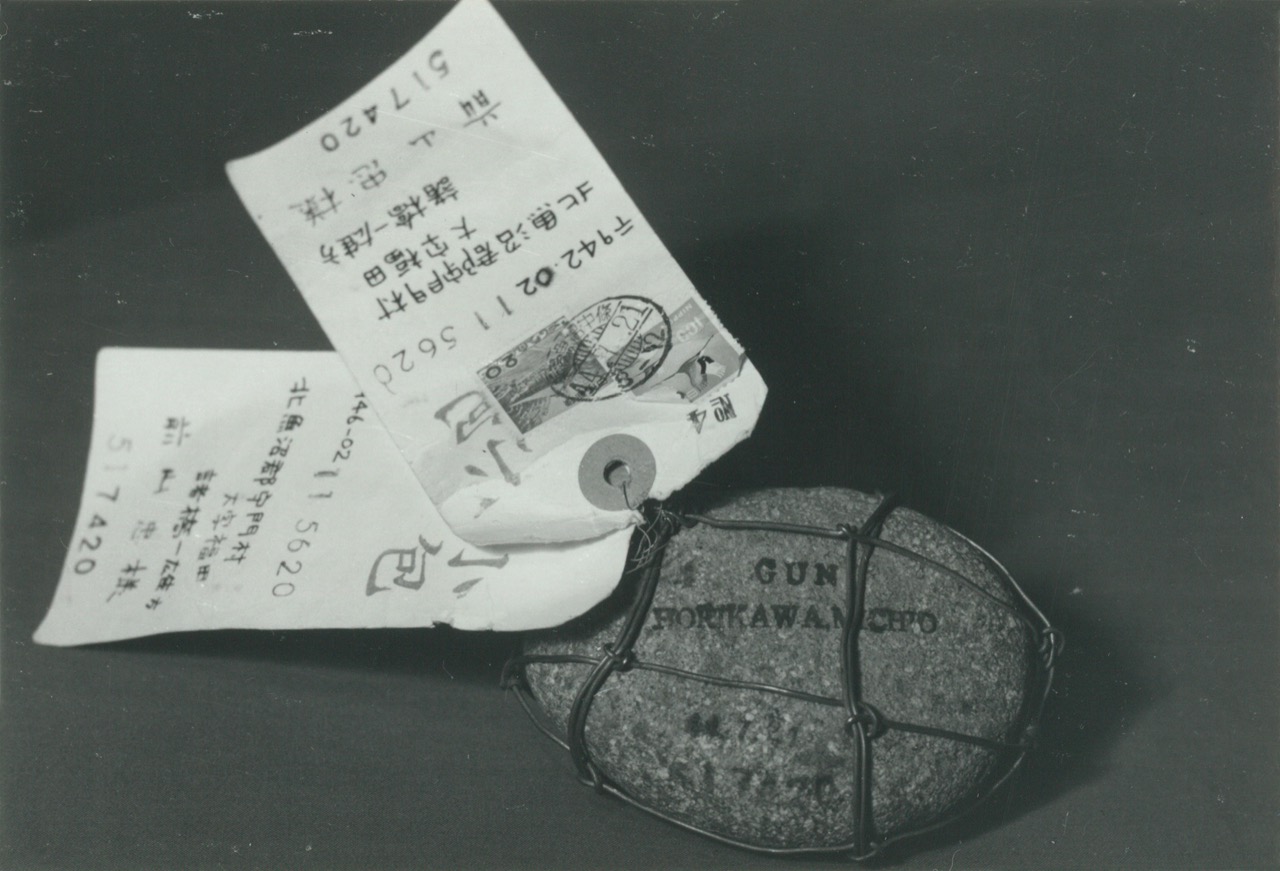

Horikawa Michio, Shinano River Plan 11, 1969. Image courtesy Misa Shin Gallery.

Shinano River Plan, by Horikawa Michio, available to view on the

Misa Shin Gallery website, or to access through video and audio tours

of the project

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that museum and gallery exhibitions remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to reflect on an artwork that is particularly significant to them and that is easily viewed online.

• • •

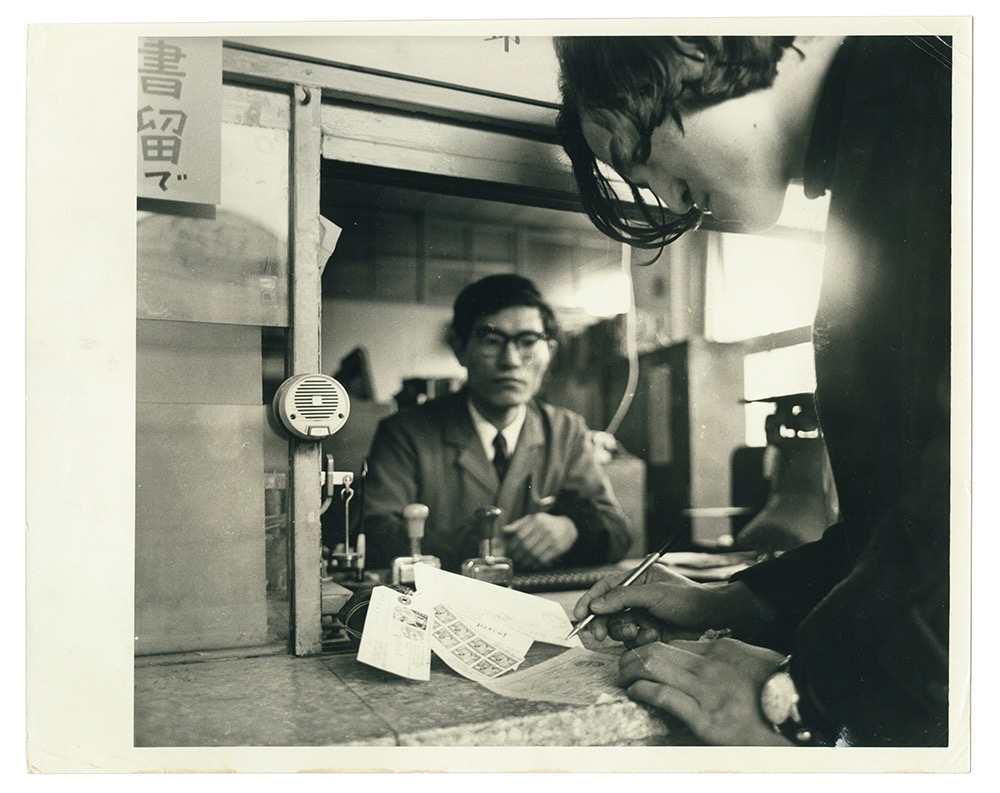

Horikawa Michio began his Shinano River Plan in 1969, in Niigata, Japan, a mountainous landscape far from Tokyo’s metropolis. To execute his work, Horikawa collected eleven stones from the banks of the Shinano River—Japan’s longest—and wrapped them in wire, which allowed him to affix address, message, and postage, and send his stones to a select group of recipients. (To form his own collection, Horikawa photographed the specimens before shipping them out.) A selection of these objects resurfaced at Japan Society in New York last spring as part of Radicalism in the Wilderness: Japanese Artists in the Global 1960s, the groundbreaking exhibition curated by Reiko Tomii.

In 1969, the Apollo 11 spacecraft landed on the moon—the mission’s number inspired the artist’s selection of eleven samples—and Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong entered a lunar landscape, grabbing celestial stones for science. (Apparently there wasn’t much else to take.) Back on Earth, many were wide-eyed for outer space, though not everyone saw it the same way: certain groups remained skeptical of NASA’s achievements. Reverend Ralph Abernathy, a close associate of Martin Luther King Jr., organized a Poor People’s Campaign march at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to protest the Apollo launch, arguing that government funds should solve human crises, not foster planetary cold war. (That same year, Gil Scott-Heron lambasted the space program with his spoken-word track “Whitey on the Moon”: “The man just upped my rent last night / ’cause Whitey’s on the moon.”)

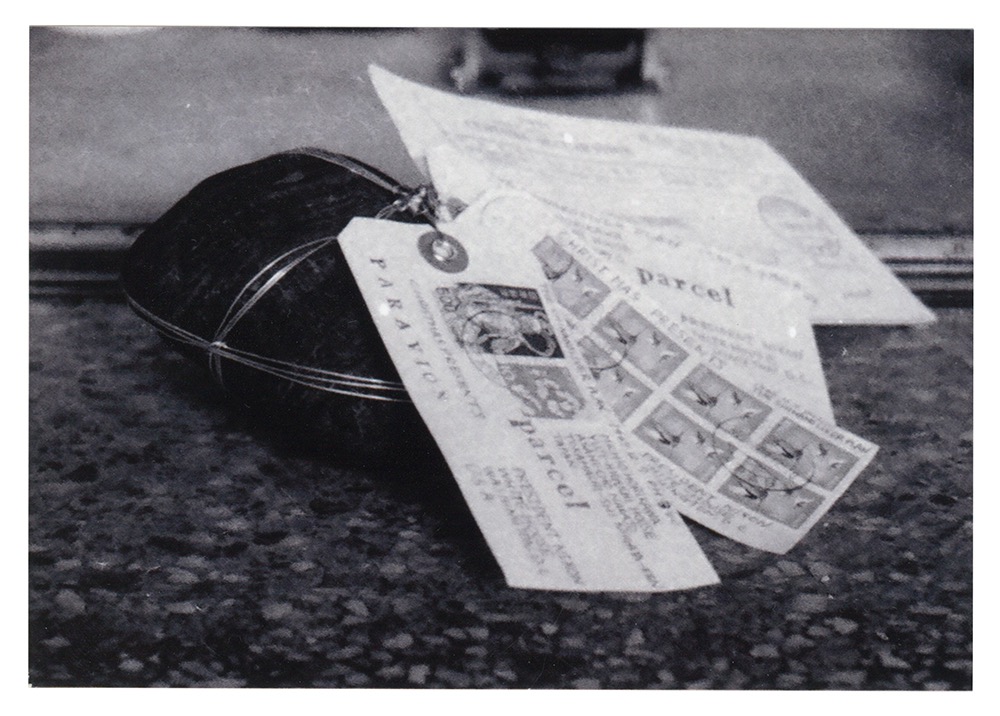

Horikawa Michio, Shinano River Plan (Christmas Present), 1969. Image courtesy Misa Shin Gallery.

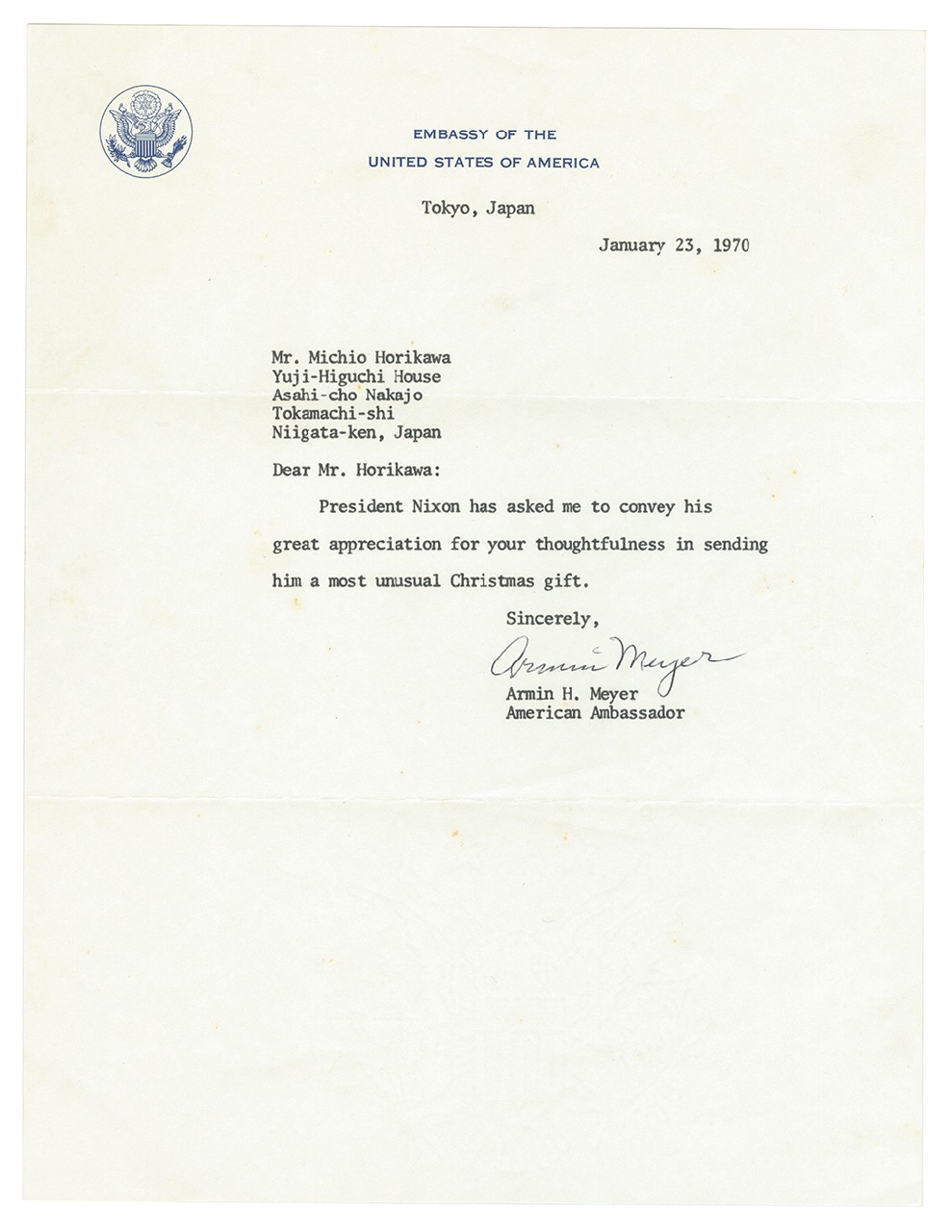

Horikawa, too, was wary of the space race, or, perhaps more to the point, he wasn’t convinced that wonder resided solely among the stars. The artist found earthly stones just as fascinating, or mundane, as their moonish counterparts. Mankind’s turn to the heavens, in other words, brought his gaze down to Earth, and it did so for others as well: the first Earth Day was celebrated a year later, on April 22, 1970. If Horikawa’s work represents a recognition of the nature of first things, as well as a return to the most basic of sculptural materials, it did not do so in nostalgic, “back to the land” fashion; rather, the artist mobilized rocks by assigning them new vectors, and dramatically changing their course. Stones flew at this time. A year earlier, students and workers in Paris had pried cobblestones from the streets and tossed them at police. Horikawa’s stones protest, too: he later shipped examples to Prime Minister Sato Eisaku and President Richard Nixon to demonstrate his opposition to the war in Vietnam. The wry note that the US embassy sent to Horikawa suggests that Nixon didn’t register the point, but the work serves as a silent memorial all the same: it is custom in many traditions to leave a stone atop a grave as a sign of remembrance.

American Embassy, Letter to Horikawa Michio, 1970. Image courtesy Misa Shin Gallery.

While Horikawa’s Plan is part political project, it also constitutes an aesthetic act, and it partakes in wider artistic tendencies of the time. Land art planted itself all over the world at this moment. In 1969, Robert Smithson poured a dump truck’s worth of asphalt down a Roman quarry while Cornell University’s A. D. White Museum staged the exhibition Earth Art. Here, Smithson imported piles of salt from nearby mines into the gallery, crowning them with mirrors, while Dennis Oppenheim cut a deep channel through the ice covering nearby Beebe Lake. In Italy, artists associated with Arte Povera (literally “poor art”) turned to trees and stones to protest commercialization. In Japan, Mono-ha (“School of Things”) also began investigations of earthly materials: Nobuo Sekine removed a massive cylinder of dirt from the ground and christened it Phase-Mother Earth (1968). Horikawa himself belonged to a group known as GUN, or Group Ultra Niigata, whose activities included spray painting fields of snow (imagine a very large, very cold Jules Olitski). But while so many of these terrestrial experiments bound themselves closely to their sites—one often had to travel great distances, to obscure locales to visit them—Horikawa moved earth in radical ways.

In its emphasis on circulation and distribution, Shinano River Plan also belongs to the practice of mail art, a 1960s movement sustained by a network of participants that collapsed distinctions between artist and viewer, sender and receiver. (Significantly, Horikawa also made ersatz stamps parodying the Japanese prime minister.) Ray Johnson presided over the mail scene with his New York Correspondance [sic] School, sending free, oblique collages, many emblazoned with his signature bunny, to a global constellation of envelope-lickers; in Canada, Image Bank, inspired by Johnson, formed a proto-photo agency, compiling pictures based on their readers’ desires. While sharing similar concerns, including the evasion of the gallery system, Horikawa’s use of the mail is singular in foregrounding matter over image, which is why it seems important that the artist didn’t package his stones but sent them simply wired, out in the open, so as many people as possible might contact—and contemplate—them directly. (Could they be minimalist versions of Chinese gongshi, or scholar’s stones?) While most mail artists were playfully critical of the commodity, Horikawa’s correspondence added a dose of antagonism to boot.

Horikawa Michio, from Shinano River Plan (Christmas Present), 1969. Image courtesy Misa Shin Gallery.

There is much to say about Horikawa’s project, but its strange title sticks in mind, especially its emphasis on the plan. The artist refused speculation by stressing organization. The idea of the plan reminds me of political projects and infrastructural undertakings (Stalin’s dire Five Year Plans, for example), and while Horikawa might have been parodying the scale of such endeavors with his decidedly DIY counterplan, the word nevertheless carries a decisive air of intentionality and execution: he set out to accomplish something. (To get a sense of this, compare Horikawa’s title to Robert Rauschenberg’s bleary-eyed paean to the moon landing, Stoned Moon, begun the same year).

But why Horikawa’s Plan today, and why discuss it here, not in a scholarly catalog but in a space of criticism? Certainly, Horikawa’s insistence on the connection between the local and global is salutary, as is his use of a national service to bridge the gap. Put another way, Shinano River Plan declares that the stuff beneath our feet carries meaning for those far away, and that institutions are necessary for making such a poetics of relation possible. In this moment when our traditional art system is (temporarily?) closed, one might begin to consider other modes of address. Now is the time to plan.

Alex Kitnick is Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY.