Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

An artist invites us to wish for a better future.

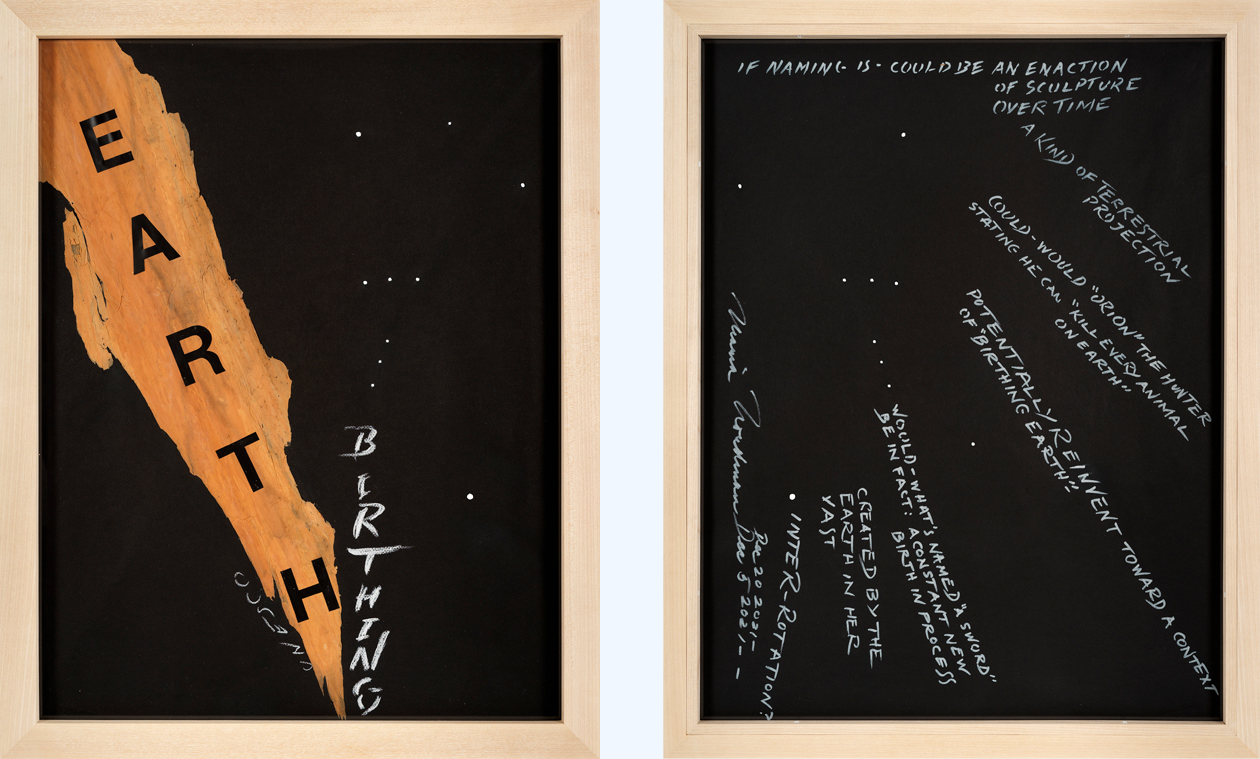

Maria Nordman, THE EARTH BIRTHING, 2021–22 (front of drawing on left, back of drawing on right). 2-sided collage on Canson paper and paper sections from bark of a molting Australian Eucalyptus tree, ink, crayon, white pencil, glue, lettering. Paper: 19 5/8 × 25 3/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Maria Nordman and Alex Yudzon. © Maria Nordman.

Maria Nordman: At the Start, Marian Goodman Gallery, 24 West Fifty-Seventh Street, New York City, through March 5, 2022

• • •

In its spirit and graphic sensibility, Maria Nordman’s work reminds one of the packaging of Dr. Bronner’s All-One Pure-Castile Liquid soap. Shorn of images and self-conscious design, the Bronner’s wrapping lays out information in an ostensibly straightforward way, with text rendered in Helvetica, stacked in blocks, and surrounded by bold colors, but the label’s economy is so extreme that it leads to a dense and dysfunctional—one might say countercultural—result, its “meaning” nearly impossible to access, except through connotation. How many times have I washed myself in the powerful aroma of eucalyptus without even considering a sentence from the bottle’s excited text? Absolute cleanliness is Godliness! it begins. Who else but God gave man Love that can spark mere dust to Life!

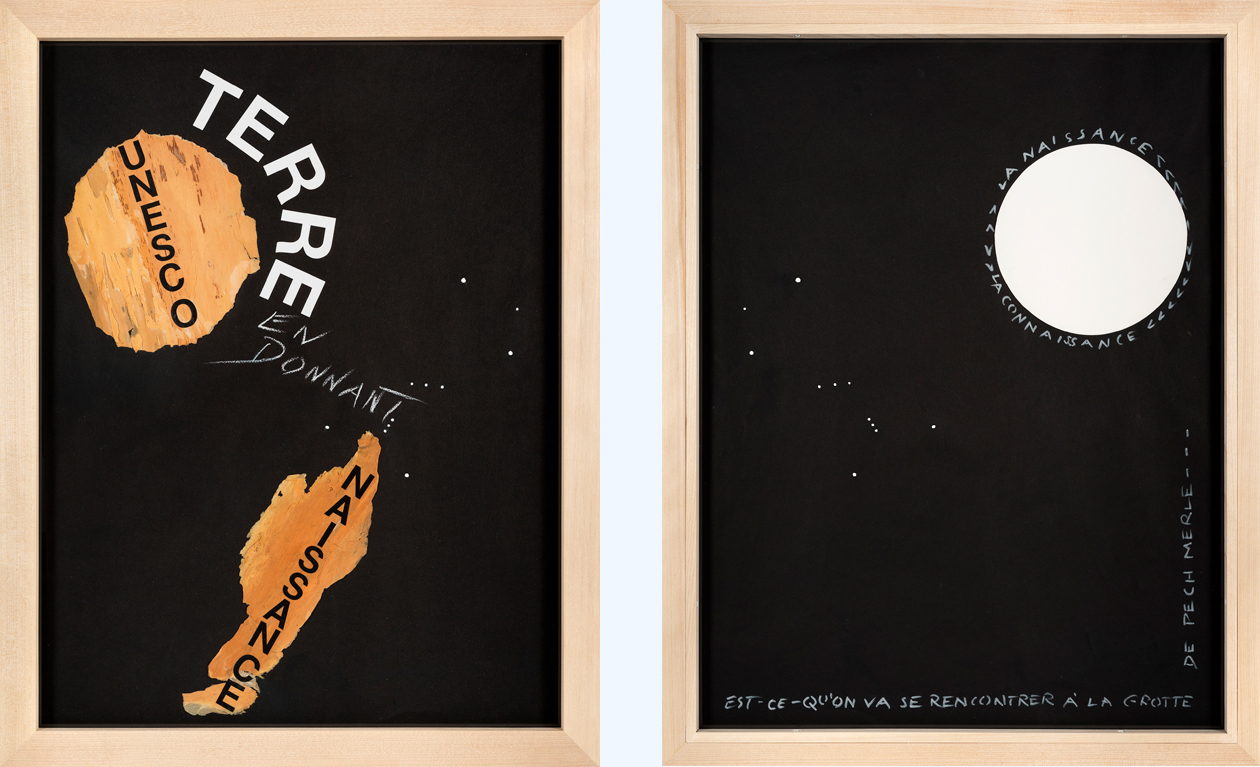

Maria Nordman, LA TERRE EN DONNANT NAISSANCE, 2021–22 (front of drawing on left, back of drawing on right). 2-sided collage on Canson paper and paper sections from bark of a molting Australian Eucalyptus tree, ink, crayon, white pencil, glue, lettering. Paper: 19 5/8 × 25 3/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Maria Nordman and Alex Yudzon. © Maria Nordman.

Nordman’s project shares something of this evangelical New Age zeal. It is a conceptual cri de coeur, a desperate hosanna, a wish for a better tomorrow, and so it’s no surprise that the artist is a product of California, the 1960s—and all that heady combination has come to connote. Trained in art and filmmaking at the University of California, Los Angeles, in the vicinity of James Turrell and Robert Irwin, Nordman and her cohort explored the environment of Southern California—its light and space—and made works as seemingly intangible as its constitutive elements, but, opting out of purity, Nordman went in a different direction, creating, in one instance, Filmroom: Smoke (1967–), a portrait of a couple smoking along a craggy coastline, which cuts the space of projection with a noirish glamor. Later, in 1983, she flooded a warehouse slated for demolition adjacent to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and, in 1995, at the same institution, carved out an exterior wall of the Geffen Contemporary, allowing dust and detritus to pool in an otherwise empty space.

Maria Nordman, Kuzaa Dunia, 2021, drawing on white cape/canvas, and Kuzaa Dunia, 2021, drawing on black cape/canvas. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Maria Nordman and Alex Yudzon. © Maria Nordman.

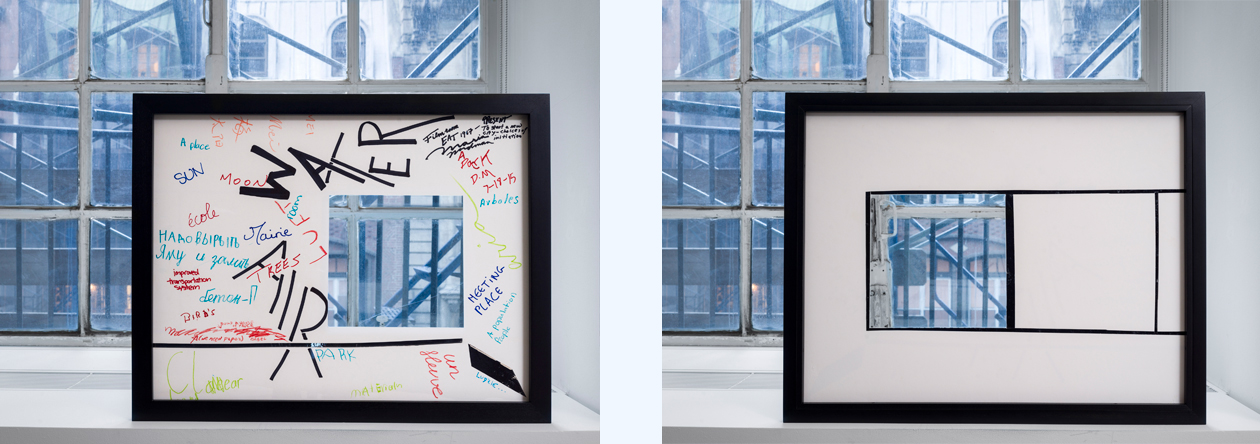

Where Turrell’s work has cooled into something akin to a VR environment, playing games with perception in the same way digital realms do (the masses were welcomed to the Guggenheim Museum in 2013 to bask in a lounge-like light show, while tastemakers like Kanye now make pilgrimage to the artist’s epic Roden Crater in Arizona), Nordman’s work has become more interactive over time. For her last exhibition in New York, a 2015 outing at Marian Goodman Gallery, Nordman ventured into Central Park—the “lungs of the city”—with capes and posters (“THE EARTH BIRTHING,” one says) that she invited parkgoers to engage with. While some activated her garments, others wrote on her slitted poster boards in order to re-envision the park and record ideas for “what a city needs,” thus connecting Nordman to a tradition of artists eager to see what art might do outside the art world; the German Joseph Beuys called it “social sculpture.” Now laid out on a table horizontally more like artifacts than artworks in her current exhibition at Marian Goodman, those answers are pedestrian: “water,” “air,” “arboles,” “fleur,” “sun,” “moon,” “a park.” We already know what we’d need to grow the world again (and, in fact, already have a lot of it), but I wonder if we are too far gone today to dream about elements when it’s aggregates—pollution of all kinds, damaged life—that really trouble us.

Maria Nordman, Air Water, 2015 (front of image on left, back of image on right). Paper, marker, Mylar, crayon. Paper: 20 × 26 1/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Maria Nordman and Alex Yudzon. © Maria Nordman.

Nordman’s work is not just about nature, however; it’s about the world’s institutions, too. A series of double-sided framed drawings installed at floor height and hinged to the wall so that they might be fingered and swayed depicts words such as TERRE (“land” or “earth” in French), TIERRA (the same in Spanish), and UNESCO, a special delegation of the United Nations dedicated to the promotion of world peace. A spirit of one-worldness—echoes of Bronner again—wafts through the show. This type of wishful global thinking, while not “incorrect,” is very much in crisis today, with walls and demagogues springing up like mushrooms the planet over. Shooting for the moon, Nordman seeks to link her utopian project to the movement of the Earth: it was no accident that her exhibition, entitled At the Start, opened in the first days of the new year. As a reminder of the potential meaningfulness of big dates (though do they ever usher in big changes?) the artist has posted the front page of the New York Times from December 31, 1999 behind a piece of plexiglass. It’s not clear if the millennial articles it contains are meant to be meaningful—some days the mosaic design of the Times doesn’t feel much more penetrable than a Dr. Bronner’s label—but certain items hum with resonance. While I was drawn to news of George Harrison’s stabbing, and noted a story on a bomb plot, seemingly closer to home is a report on the United Nations’ seventh secretary-general, Kofi Annan, and his “unsettling” ways.

Maria Nordman, Dec. 31, 1999 (detail on right). Newspaper. 11 5/8 × 13 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Maria Nordman and Alex Yudzon. © Maria Nordman.

The first time I visited the exhibition all the lights were off and, since it was evening, the gallery was extremely dark. Crank-powered solar flashlights sitting atop a pedestal near the door cast an eerie glow. Grabbing one and ambling around, I caught glimpses of fossils in tall rolling sculptures that double as archives and, in a back room, a collection of the artist’s catalogs opened and standing on their bottom edges, as if ready to come to life. The refusal of artificial illumination evoked endgame scenarios, inviting the viewer to imagine what the world will look like when the electricity finally does go out (perhaps Nordman’s is a kind of survivalist Conceptualism, an aesthetic version of starting a fire in a trash can), while at the same time, it asks us to sync ourselves with the rhythms of the day, to imagine a net-zero existence where, as the backpackers say, we take only memories and leave only footprints. When I returned to the gallery on a snowy gray Thursday I could grasp things slightly better (the ponchos hanging from the ceiling turned with new vitality), but the searching feeling of looking in the dark seemed somehow like the more appropriate lens.

Maria Nordman, Geo-Aesthetics/Presencing, 2013. Artist books, drawing insert on vellum, Plexiglas stand. Koln: Walter Konig, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Maria Nordman and Alex Yudzon. © Maria Nordman.

Nordman has never received the attention she deserves in the United States, not only because the artist lived for many years in Germany (the country of her birth) and completed a number of her most important projects there, but also, I think, because her work is at once too scrappy and too utopian for American tastes; it encompasses and promises so much. While Nordman’s practice might remind one of any number of her contemporaries—her play with words invites comparisons to the gnomic statements offered by the late Lawrence Weiner, while her architectural interventions speak to Dan Graham’s pavilions—her efforts belong less to art movements than to a fever dream of world transformation. It’s something tiny that wants to do something big, and maybe, linked to a host of other efforts, one day it will. Nordman dates many of her works with an open-ended dash to insist on both their presence and unfinished quality. There’s something rather messianic to her position, and, like with all messiahs, one is left with a terrible feeling of doubt and wonder when beholding her offerings. One imagines what things might be like—how amazing, how changed, how beautiful—if and when her art’s promise comes to Earth, and yet these days it’s hard to imagine that such an Edenic world could ever grow.

Alex Kitnick is Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.