Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

Black flags, white crosses: Latin American political art in an

era of oppression.

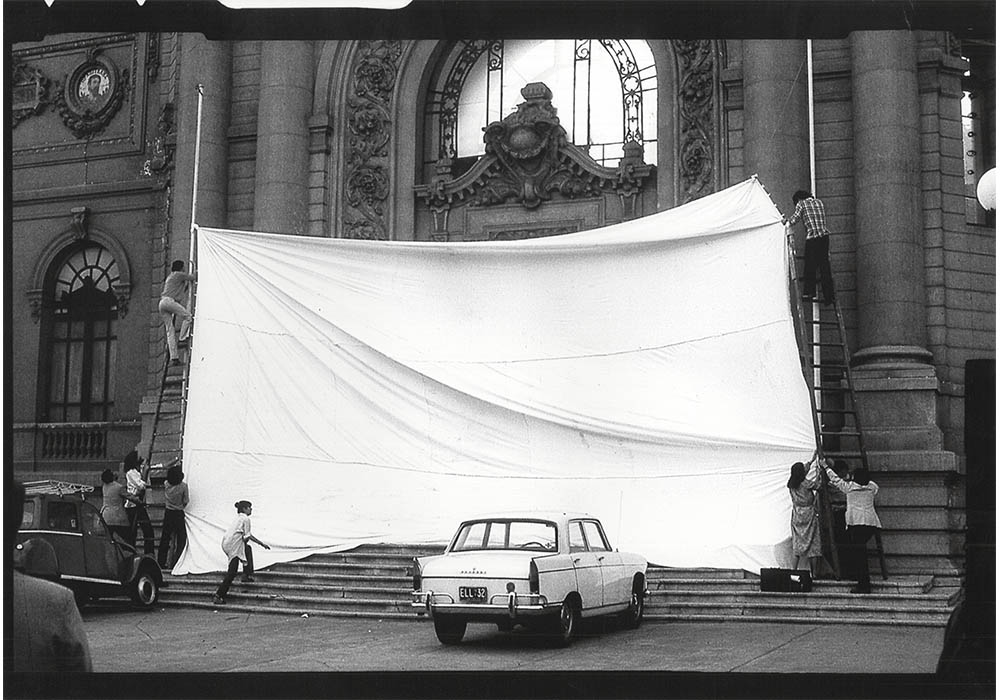

CADA (Colectivo Acciones de Arte), Scene Inversion, Santiago, Chile, 1979. Digital print on photographic paper, 15 × 11 inches. Courtesy C.A.D.A. / 1 Mira Madrid Gallery.

The Counter-Public Sphere in the Condor Years, curated by Nicolás Guagnini, Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, 50 East Seventy-Eighth Street, New York City, though January 15, 2021

• • •

Forty-five years ago, under the name Operation Condor, the US government began a series of ruthless interventions in the political life of various Latin American countries, working alongside local military and right-wing groups. Democratically elected presidents were deposed, dictators installed, citizens “disappeared,” and even the smallest acts of dissent stifled. A compact exhibition dedicated to art produced during this time, The Counter-Public Sphere in the Condor Years at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, or ISLAA, curated by the artist Nicolás Guagnini, presents a series of aesthetic strategies for standing against repression, albeit in often oblique ways.

The Counter-Public Sphere in the Condor Years, installation view. Courtesy Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA). Photo: Julio Grinblatt.

Political art is frequently associated with graphic representation, posters decrying oppression and championing liberation, but many of the works in this show reroute or recode the real in subtler ways. Scene Inversion (1979), for example, staged by the group CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte) and presented here as a five-minute video, consisted of a parade of milk trucks that wove its way through the streets of Santiago, Chile. (The truck drivers had been told a story as to why they should reconfigure their routes that day.) Ultimately parking in front of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, which had a big white banner illicitly hung on its façade for the occasion, the trucks gathered for a strange group portrait before disappearing back into the city. Salvador Allende’s socialist government had promised Chilean children a milk ration to fight malnourishment, a promise broken by Augusto Pinochet’s regime, and CADA wanted to address the situation, but clearly they wanted to say something about art, too, because why else use the museum as an institutional frame? The museum makes things visible and plays a civic role, but to make it work, in this case at least, it had to be inverted, repurposed, turned inside out.

Lotty Rosenfeld, A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement, Santiago, Chile, 1979 (detail). Gelatin silver prints, 23 3/16 × 35 inches. Courtesy the artist / 1 Mira Madrid Gallery.

A project by Lotty Rosenfeld on the opposite wall similarly takes to the streets. Rosenfeld was a key member of CADA, and her work, too, engages a public utility—in this case, a road on the outskirts of Santiago. Starting with the white lines that divide traffic lanes, Rosenfeld glued strips of fabric atop each readymade mark to create A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement (1979–80). The process of the work’s making is documented here in video, as well as in a series of photographs, each archive showing Rosenfeld’s body crouched close to the road. (The video is also included in MoMA’s recently rehung collection galleries.)

The Counter-Public Sphere in the Condor Years, installation view. Courtesy Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA). Photo: Julio Grinblatt.

The simple gesture generates complex wordplay—one thinks, for example, of what it might mean to “cross the line”—but certain details in the photographs stand out, starting with the fact that Rosenfeld signed her name on the street, taking responsibility for her act and also, perhaps, asserting authorship. I was particularly struck, however, by the triangular stamp on the board mounting the photographs: Esta línea es mi arma / Lotty Rosenfeld / Chile, it states. “This line is my weapon.” Guagnini seconds the artist’s militant reading of her work in his catalog essay, calling the project “historical dynamite,” but I was left more with an image of aftermath than imminent explosion. The world had already gone off. I can’t shake the idea of A Mile as a graveyard, one anonymous marker lined up after another, counting the dead by the mile, creating a memorial without names.

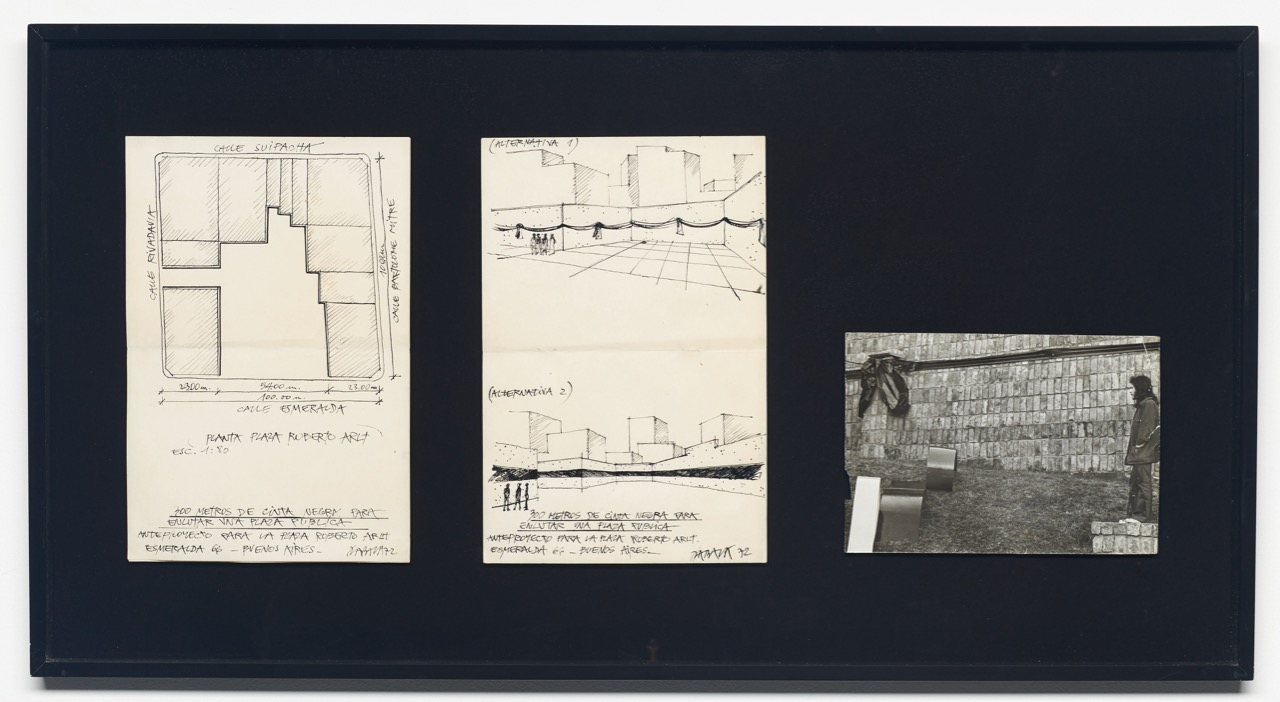

Horacio Zabala, 300 Meters of Black Tape to Mourn a Public Square, 1972. Ink on paper and gelatin silver print, 19 6/16 × 36 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Herlitzka + Faria. Photo: Arturo Sánchez.

The specter of death also haunts Horacio Zabala’s 300 Meters of Black Tape to Mourn a Public Square (1972), another work invested in the measurement of public space. Invited to participate in an outdoor sculpture exhibition staged in a Buenos Aires plaza, Zabala hung a black sash on the surrounding walls, every so often tying it in a bow. Artists had to be subtle at this moment if they wanted to say anything critical in public space (let alone mourn its passing), but even Zabala’s rather opaque parade of fabric was too conspicuous (when you’re a censor, I guess, you can’t be too paranoid), and the authorities quickly took it down. The two sketches and single photograph included in this exhibition are all that remain of the artist’s intervention, a tiny archive made all the more precious by the fact that every other part of the work has disappeared—and who knows what and who else.

Antonio Dias, Eye Patch, 1969. Acrylic on black fabric, 33 × 36 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist’s estate and Galeria Nara Roesler.

Four out of the five pieces in this meticulous show, in fact, are more documentation than standalone works, though this is a distinction that the conceptual art of the time often sought to trouble. Still, Antonio Dias’s Eye Patch (1969), hung on a wire traversing the gallery, stands out. Before moving to Italy in the late 1960s (after a stop in Paris for ’68), Dias worked in his native Brazil crafting a bodily brand of Pop art that stressed the violence of the country’s military regime. Upon arriving in Italy, however, he mined a more conceptual vein (think, for example, of Joseph Kosuth’s stark definitions), and yet he maintained an activist’s desire to engage the real. His Eye Patch is a kind of portable public intervention, a black flag with the word REALTÀ (Reality, in Italian) painted backward.

Flags and banners unfurled across mid-century art, perhaps because the nation-state itself was in crisis: one remembers Jasper Johns’s Flag (1954–55), the stars and bars coagulated with wax and newspaper clippings, and Hélio Oiticica’s Seja Marginal, Seja Herói (1968), which blew in the wind at Rio de Janeiro’s Festival of Flags, and at any number of Tropicália concerts. The flag, Pierre Nora has written, is an important site of memory, a place in which we invest the energies and affects of national histories. But Dias’s banner implodes the flag’s nationalist connotation. Reality is backward, it tells us, but would raising it up a flagpole turn things around? Like the other interventions in this show, Eye Patch is suffused more by mourning than hope (while an eye patch abets healing, it also obscures vision). Derrida spoke of “the work of mourning,” and certainly the art of the Condor Years belongs to that tradition, but it is a mourning riven less by melancholia than it is touched by militancy.

Alex Kitnick is Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.