Gia Kourlas

Gia Kourlas

Incarnations collides dance and physics—and a little Yvonne Rainer.

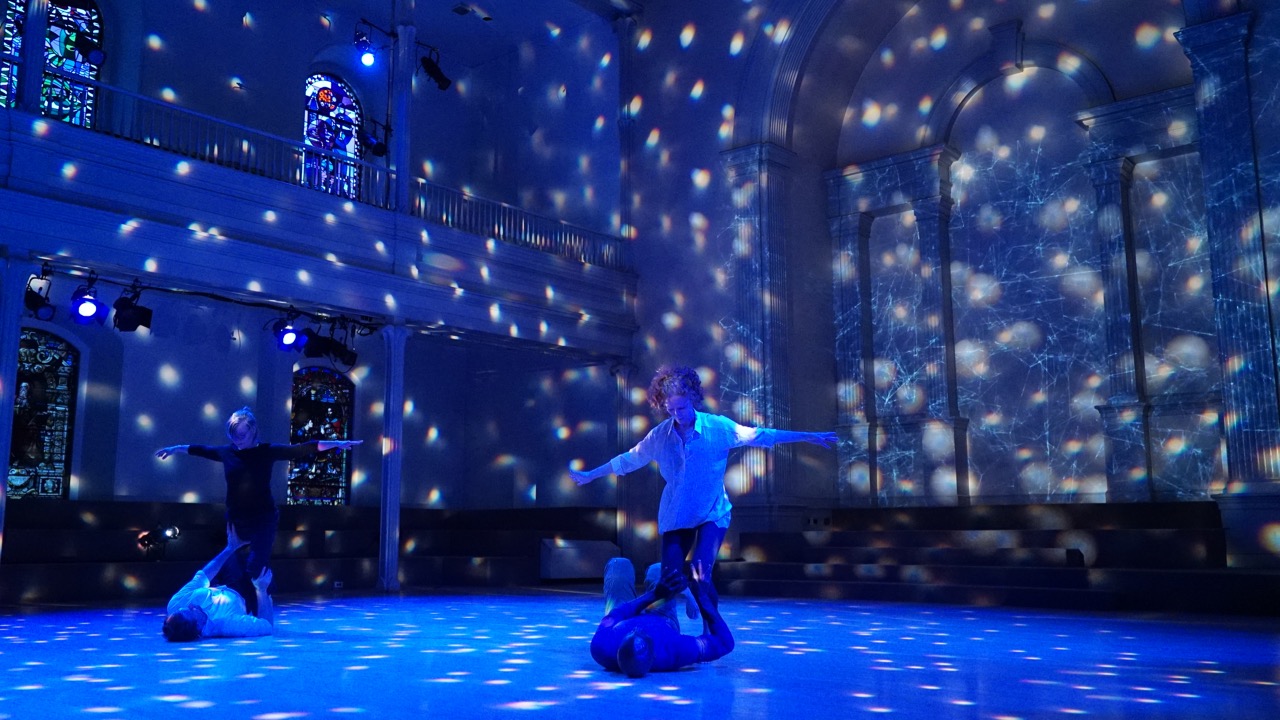

Incarnations. Photo: Alexis Moh.

Incarnations, Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, 131 East Tenth Street, New York City, March 16–18, 2017

• • •

An incarnation is a person who embodies, in the flesh, a deity or a spirit. From the Shiva to the Sylph, the dance world is full of such mythic characters. Emily Coates, a ballet dancer who fell in love with postmodern dance by way of Yvonne Rainer, adds her own twist by diving into physics to bring two gods down to earth. In her new Incarnations, there is Apollo, the Greek god of light, music, and much more, and the Higgs boson, nicknamed the god particle.

At one point in Coates’s curiously gripping work—both serious and playful, it unfolds through a witty blend of movement and text—she explains to the audience in a clear, professorial tone that the performance “is our laboratory. It’s a place to research time, space, gravity, light. We’re colliding the knowledge that dancers possess with the knowledge that physicists create.”

While that collision is felt in Incarnations, it isn’t entirely explicit, and such mystery is a good thing. Dance and physics share certain traits; both require imagination and a suspension of disbelief, as well as a desire to express or to explain the unexplainable. Movement, it turns out, connects the two.

Though she is credited with the creation and choreography of Incarnations, her first evening-length work, Coates very much has a partner in Sarah Demers, a professor of physics at Yale University. (Coates has directed the dance studies curriculum there since its 2006 start.) A former member of both New York City Ballet and Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project, Coates, with Demers, has led workshops on physics and dance throughout the US. Next year, their book on physics and dance will be released by Yale University Press.

Their bond is apparent in the lecture-demonstration structure of Incarnations. Demers, slender and tall with a gangly grace, relates dry scientific facts with the kind of clarity and enthusiasm that makes you wish she had been your teacher. Through her, Coates made a discovery: when physicists speak about the Higgs boson—the elusive subatomic particle discovered in 2012—they gesticulate wildly. Their arms become emphatic, their hands ornate.

As Demers walks toward us in a strip of light while describing her research, Coates, a few feet away in another, walks in the opposite direction while narrating the patterns of Demers’s movement. If the word “particle” is mentioned, Demers’s accompanying gesture is pinched fingers. “Particle collision” means that the palms of the hand push the arms out, never in.

Incarnations. Photo: Alexis Moh.

In a film projected on the back wall, we watch an interview with the particle physicist Melissa Franklin as the dancer Jon Kinzel, standing downstage, mirrors her gestures and is soon joined by others—Lacina Coulibaly, Iréne Hultman, and Coates. Serene, somehow evoking a quietly slow-motion cascade of falling snow, they swirl around the stage under cool blue lighting, seemingly floating until gravity takes over and they melt to the floor. Are they dancers or glittering particles? Somehow, a bit of both.

And what about Apollo? Coates weaves iconography of the god over history into her choreography, linking together static poses to create an undulating chain of positions. But George Balanchine’s ballet Apollo (1928), specifically the version danced in the 1960s by Jacques d’Amboise—his unmannered, athletic performance remains penetrating, even a vintage performance on video—is integral to Incarnations. Balanchine, who cofounded City Ballet with Lincoln Kirstein, changed ballet by infusing it with speed, athleticism, and a jazzy American spirit.

Coates performs and then deconstructs d’Amboise’s Apollo solo in Incarnations to reveal both her own lineage as well as to show how a dancer can hijack a piece of choreography and, through reinterpretation, alter it drastically. But she first relates Balanchine’s advances in ballet to physics by showing the way Balanchine changed the preparation for a pirouette, thereby giving the dancer the ability to turn with greater force.

Instead of beginning in a fourth-position plié, with both knees bent and the weight balanced evenly between two feet, he had the dancer stretch her back leg into a deep lunge and extend the opposite arm upward on a diagonal. The dancer, by pulling in her arms tight, could then turn faster. “That’s torque,” Demers explains. Moving the point of application of the force—that rear foot—away from the access of rotation creates “a more powerful turn for the same force.”

Even if you knew it already, it’s illuminating. While Incarnations looks outward, seemingly beyond dance to a larger universe of gods and science, it is also personal to Coates—a survey of her own history in dance, which took her from Balanchine to Rainer and now Yale. But her exploration, in turn, also looks at larger issues within the form: How is dance passed on from one body to the next? How does it transform? Coates’s dancers, endlessly fascinating in Incarnations, move differently but possess a profound depth of kinesthetic knowledge and history. Hultman is a Trisha Brown veteran; Coulibaly, from Burkina Faso, has a background history in African dance; and Kinzel is a much-admired choreographer and improviser.

In this mix, Coates is almost too light, too balletic to match their haunting vitality, but bringing in their artistry is what gives Incarnations its bearing and breadth. Coates, it turns out, has another powerful dance presence up her sleeve in the form of a special guest star. Red balls rain down on the Danspace Project stage from the balcony to signal the entrance of Rainer, the groundbreaking postmodern choreographer, who invades the work with a cameo appearance as Apollo. (The red balls are a reference to a Rainer prop.) Her voice announces grandly from above: “I shall now descend.”

The moment she steps onstage, complaining that her spine “is like a twisted stunted fallen tree disappearing in the sun,” Rainer begins to infuse her manic text—ranging from a reading of Etel Adnan’s novel about the Lebanese Civil War, Sitt Marie Rose, to sly references to the Trojan War—with movement both frenzied and hesitant. She delivers a show within a show, serving up jokes with political overtones while skipping, spinning, and scurrying across the stage.

Incarnations. Photo: Alexis Moh.

When Rainer’s rant is over, she poses as Balanchine’s Apollo—with Coates, Demers, and Hultman as the three muses—to recreate some of the ballet’s iconic tableaux. During one moment, Demers asked, “Yvonne, what did it feel like to change the way people view dance?”

She replied, “It feels different at different points. You don’t know it’s changed until you’ve done it.” Rainer paused. “Yeah. It feels pretty good.”

Incarnations does more than bring science and art together—it carves out a place where classical and pedestrian movement can meet. In both instances, it’s humane. With wit and spirit, the gods came out to play.

Gia Kourlas was the dance editor of Time Out New York from 1995 to 2015. Since 2000, she has regularly contributed to The New York Times, where she writes dance reviews, news items, essays, and features. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Dance Magazine, Dance Now, and Vogue.