Jennifer Krasinski

Jennifer Krasinski

In Joy Williams’s novel, a girl travels a post-apocalyptic landscape.

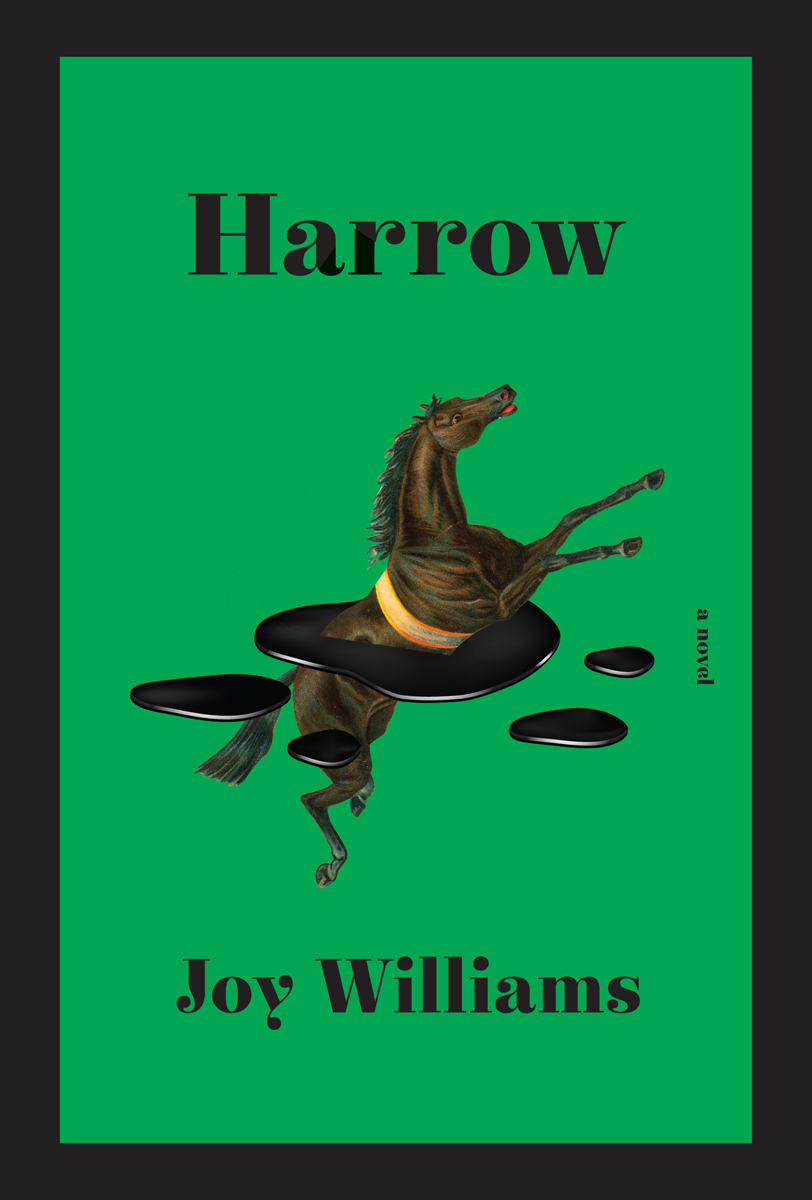

Harrow, by Joy Williams, Alfred A. Knopf, 203 pages, $26

• • •

It is the rare author who offers up a work so brimming and rich that a reader is freed from the banalities of judgment to instead bask in the sentences, the stories, raveling out right before our eyes, one after the other after the blessed other. Hyperbolic? Absolutely, but Joy Williams is a writer of such daunting intelligence and craft that I am giddy and remain so because her newest novel, Harrow, is here and I’ve read it and will admit that having it in hand is almost enough for me. Williams’s other devotees will recognize her usual subjects here: environmental disaster, a lone girl negotiating her own strangeness in the strange world. This time around Williams pairs us with Khristen, whose origin story is framed by the minutes that she, as an infant, died and then came back to life: “My mother was convinced that I had been somewhere, in some frightful chaos of non-being that nevertheless contained an observable yet incomprehensible future to which we would all be subjected.” Khristen’s presence is thereafter marked by this traversal. She doesn’t talk much. She weirds people out.

In the sweeping first section of Harrow, Williams whisks Khristen from birth to a boarding school, then—her father dead, her mother absconded to a “visionary conference” at a resort—looses her alone in the world, which is suspended in the aftermath of an unnamed, undescribed act of destruction that has left everyone and everything in a crippling daze. “The people I saw didn’t seem to be traveling,” Khristen describes. “They were milling, like little flies after a rain.” Nature is obliterated, poisoned, and few seem to care; civilization, such as it is, and the powers-that-be seem hell-bent on just forging ahead. Williams builds her novel like an ark, bringing along who and what she needs to get Khristen where she’s going, and to say what needs saying; characters are deployed as swiftly as they’re pitched overboard once they’ve played their part. Khristen is the receiver of stories, information, instructions: in Brittany, a surly teenaged self-dubbed “post-humanist,” Khristen finds herself with a temporary enemy; Brittany’s mother, an eco-critic named Freida, explains to her how it is “our moral destiny to technologically dominate the earth.” A pack of adolescents who call themselves “The Fallout” show Khristen the way to the home of an aged professor, who in turn lends her a truck for the next leg of her journey.

From there she drives to a decrepit resort built near Big Girl, a sickly, stagnant lake, and there meets “the Institute,” a cell of motley elders who conduct end-of-life suicide missions in the hope of redirecting the doomed, hurtling world. “I want to be part of the future,” declares Foxy, a former “drug addict,” assessing the value of a demise well-spent blowing up old institutions. (Her chosen target: the United States Navy.) “We are the agents of collapse in this delicious campaign against the morally colorless and corrupt. I’m ready for a proud and wolfish death. With my death, an active death, I’ll make the world more wolfish.” But in Williams’s appraisal, blood isn’t worth that much anymore: not when spilled, not when donated to those in need. Not even when it binds family members to one another. In one of the novel’s grimmest, funniest scenes, a mother, Barbara, decides to break the news to her precocious ten-year-old son Jeffrey that his father has killed his beloved grandfather—by having the murder scene illustrated in frosting on top of the boy’s birthday cake. Alas, her plan is foiled when the baker mistakenly recreates Goya’s gory masterpiece Saturn Devouring His Son instead. “You’ve just left the first decade of your life behind,” Barbara tells a confused Jeffrey. “You’re a little man now.” It seems rites of passage not only announce the passing of time, of life, but also how insatiable, how cannibalizing, is the already wolfish world.

Williams’s tales are always woven throughout with discourses on the human condition. At times her stories feel like parables, perhaps echoing something of the sermons her father, a minister, would deliver to his congregations when she was a young girl. She is a writer whose wild-mindedness seems to bloom from her prodigious attention to our moral incompetence—our confusion, our contradictions—judiciously lacing her insights with just enough acid to keep a reader from swallowing anything too easily. In Harrow, she identifies many illnesses of spirit she believes feed our propensity for destruction: a disconnection from the ability to grieve fully; the overvaluation of meaning where awe might keep us alive and thriving for a lot longer; the paralysis that besets those who recognize they are part of the hole of our sinking future. In the final section of the novel, Jeffrey—now a judge, though still only a child—gives Khristen Franz Kafka’s story “The Hunter Gracchus,” in which a wrong turn during a man’s transport to the afterlife leaves him aimlessly sailing the world, neither of it nor rid of it. (Kafka’s story was published posthumously, unfinished, in a sense relegated to limbo, like its protagonist.) Gracchus’s is a death without death, a life without life—similar to Khristen’s fate. For all of her encounters, she feels less and less vivid with every turn of the page, until her story breaks off to the sound of a great crack and readers are released back into their own.

Entire generations can be deranged by the fictions they inherit or propagate. Tales of the apocalypse are, in part, allegories for the authorial ego up against the limits of imagination—not Williams’s, per se, but that of humanity in the face of a stark reality, of mortality. After all, it takes some pretty swollen cojones to entertain even for a hot second the idea that all of civilization will end when you do. Yet the new forms can only be forged by staring directly into the abyss, by passing through the fire and brimstone of one’s own mind. “The old dear stories of possibility,” Williams writes. “No one wanted them anymore, but nothing had replaced them.” The book offers no saccharine words of solace, no glimpse of a glowing horizon even in the far distance. Instead, Harrow leaves us grasping at fraying narratives like lifelines thrown into a mire where law is a palliative measure, absolution is idle self-soothing, and the nighttime during which we and other animals once dreamed has been extinguished by the artificial light of those who fear what flourishes in darkness. Williams’s novel may not promise a new world, but it makes sure we understand that the fate we have written for ourselves is not so merciful that we are anywhere near our end.

Jennifer Krasinski is a writer and critic who works as the editorial director of Artforum digital.