Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

The artist’s portraits pursue “shameless generosity.”

Jennifer Packer, Tia, 2017. Oil on canvas, 25 × 39 inches. Photo: Matt Grubb.

Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing, curated by Melissa Blanchflower with Natalia Grabowska, Serpentine Gallery, Kensington Gardens, London, through March 14, 2021

• • •

Editor’s note: As of this writing, Serpentine Gallery is temporarily closed to the public due to COVID-19 concerns. An online version of the exhibition (including images, video and audio interviews, and more) is available on the gallery’s website.

• • •

I am transfixed by Tia’s hands, which sit folded in her lap, flickers of rose, salmon, watermelon pink for nails. Tia’s feet, sole of right resting against arch of left, her patterned socks with their turquoise toes and bright floral sprays of orange, crimson, yellow, indigo. The pillow case behind Tia’s head, flowers again, smaller and more delicate, purple, pink, periwinkle, green leaves and stems scattered across white, Tia (2017). Hands, again, in Jess (2018), gently folded in the lap, again, their painted lines energetic, elastic, careful, as in full of care, one fuchsia nail throbbing quietly among the rest, a smudge of violet on the knuckle. In Tobi (2019), a vision in magenta, legs drawn to his chest, bare feet snag the eye. Modeled with the merest of dark lines, the flesh of Tobi’s feet is rendered in swathes, patches, dabs, smears, scrapes of ruby, cerise, fandango, bubble gum, carnation pink. A topography of tenderness and solitude—the heat of a body in quiet repose—existing, being seen. Look closely: peeking from beneath the cushion on which his feet rest is another pair of feet, half-sketched but identical. A different version, a previous possibility, the multitudes of a body? Jennifer Packer’s portraits hold time, reveal its passing and their making within it.

Jennifer Packer, Jess, 2018. Oil on canvas, 30 × 24 inches. Photo: Jason Wyche.

In other paintings it is a set of speakers, a fan, an iron, knives on a wall-mounted magnetic strip, a purple jacket, a door, a window, a seafoam-green toilet seat, a mattress, the cuff of a sleeve—minor-seeming details—that pull the gaze, give shape and dimension, albeit shifting and wayward, to Packer’s images. “What’s the significance of the difference between a person and a chair, in terms of social or cultural value?” the artist has wondered. “I’m not interested in the hierarchy that portraiture suggests. I’m interested in the codependency of humans existing in spaces along with other really important information. I’m interested in environment as much as the figures that sit within it.” Environment is a resonant word for Packer’s works—canvases and drawings of varied sizes, from tiny and jewel-like to large tableaux—thirty-four of which are displayed at the Serpentine Gallery (now temporarily closed due to COVID restrictions). They are less of subjects than of atmospheres, climates, sensations, even emotions. Humans—“It’s not figures, not bodies, but humans I am painting”—appear as fields of color and loose, dissolving shapes that emerge momentarily in specific parts—an ear, a mouth, eyes, knees, feet, hands—implying but never quite becoming coherent pictorial representations. And why should they?

Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing, installation view. Photo: George Darrell.

The portraits depict friends and artistic peers, painted over varying spans of time, and they radiate a warm, observant intimacy. “Representation and particularly, observation from life, are ways of bearing witness and sharing testimony,” the artist has said of the Black individuals she paints and how they deserve to be seen and considered, “to be heard and to be imaged with shameless generosity and accuracy.” They are political, as all representation is, but also deeply personal—about the time that passes in the studio, what occurs between painter and subject, their past and present, relationship, awareness, energy, labor, love. Packer blurs figuration and abstraction—or “dissolution,” as she prefers to call it—giving the sense that there is more to a person than his, her, their context or surface and what can be straightforwardly shown. How to do justice to the dynamism and complexity of an individual? How to paint an exterior with respect for its interior life, which can never be fully accessed, perhaps only sensed or felt, hinted at or glimpsed in passing? In some works, the human or humans are not named, as in Lost in Translation (2013), Vision Impaired (2015), or the striking charcoal and pastel drawing—one of four included in the exhibition, each holding as much weight and gravitas as the paintings—The Mind Is Its Own Place (2020). In these images, bodies merge, light anoints, colors swell, overlap, and blend, as if a body could be anything, which of course it can.

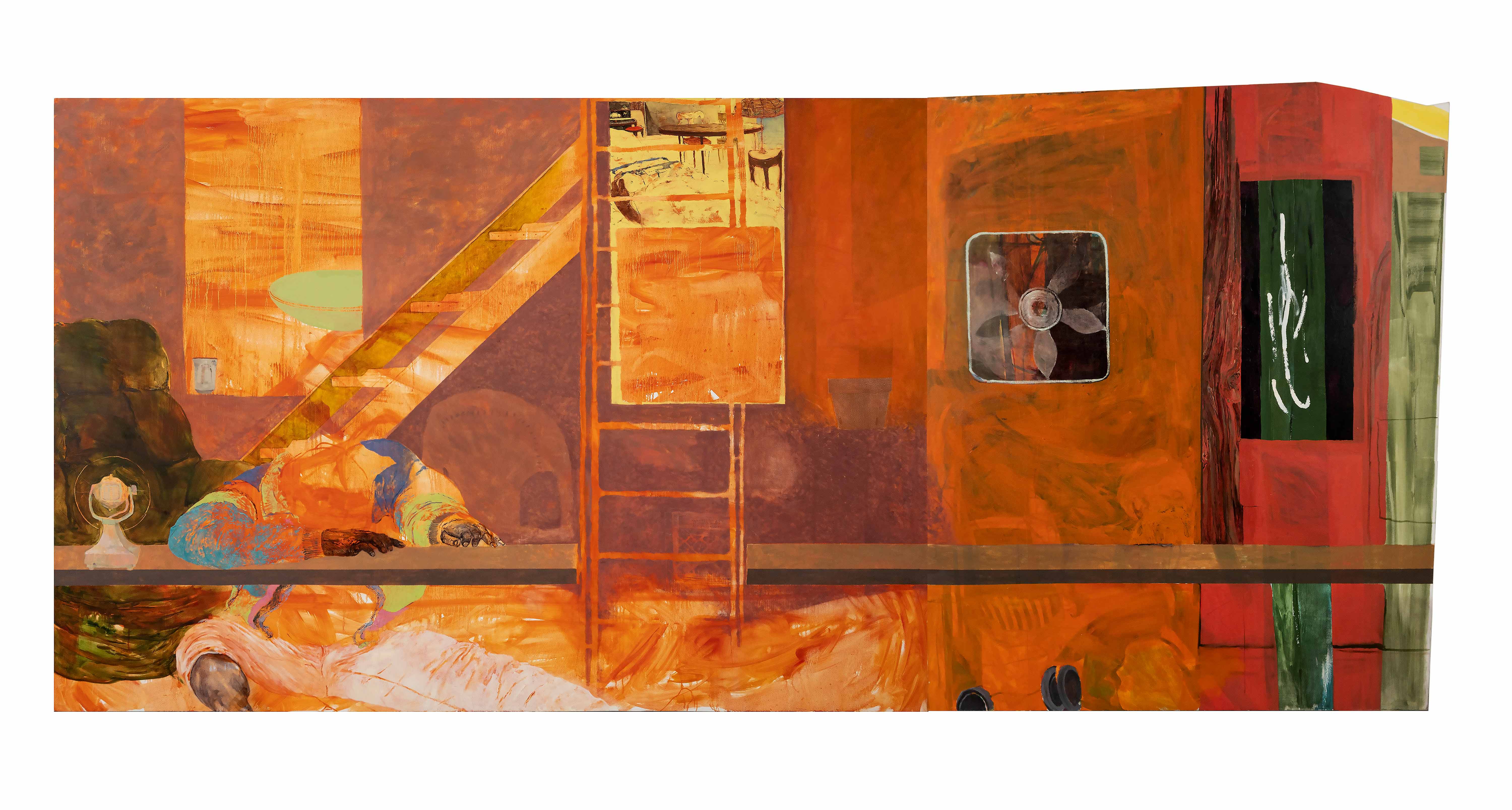

Jennifer Packer, Fire Next Time, 2012. Oil on canvas, 72 × 156 inches (diptych). Photo: John Betancourt.

Two of the largest works at the Serpentine are composite domestic scenes, assembled from parts observed, remembered, and imagined. Fire Next Time (2012), a reference to James Baldwin’s 1963 book, is suffused with hot hues of orange. A man slumps over a slender counter, legs splayed beneath, around him a scene of discordant geometries—a ladder, stairs, a plump hunter-green chair, a flower pot, a milk crate—is rendered in different treatments of paint, impressionistic, drawn, poured, dripping, as though the time and space of the painting have been flattened and collapsed. Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!) (2020) is similarly constructed around a figure in repose on a couch in the foreground. The image is dominated by an almost hallucinatory field of chartreuse, punctured here by a large square of pink, there by a window of sky blue framing a wine-colored bird in flight—a picture within a picture. Another picture within the picture is a poster, partly covered by a square fan, that reads Too Blessed to Be Stressed in curly and joyful colored script decorated with illustrated party bunting—a poster that hung in twenty-six-year-old Breonna Taylor’s bedroom when she was murdered by police on March 13, 2020.

Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing, installation view. Photo: George Darrell. Pictured: Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!), 2020.

How to picture, or perhaps process, grief is another of the artist’s subjects, as in her flower portraits, like Breathing Room, Flowers for Frank Bramblett (2015) and Say Her Name (2017). The former is for the artist and teacher Frank Bramblett, who died in 2015, while the latter remembers—commemorates? summons?—Sandra Bland, the twenty-eight-year-old African American woman believed by many to have been murdered while in police custody on July 13, 2015, and whose death began the ongoing #SayHerName social justice movement. Pale roses, white lilies, carnations, amorphous flowers of teal blue, coral, mauve, pink, and tangled greenery radiate energetically from the center of the canvas, like a centrifugal force, reaching to its edges as though they continue to grow wild. Some are detailed, while others are sparely drawn, smeared or scraped into the painted surface against a background that spreads from white to rich gold to charcoal black.

Jennifer Packer, Say Her Name, 2017. Oil on canvas, 40 × 48 inches. Courtesy the Artist, Corvi-Mora, and Sikkema Jenkins & Co. Photo: Matt Grubb.

These paintings, like the portraits, both recall and remake, infiltrate and challenge various art historical genres. Packer cites artists like Manet, Goya, Fantin-Latour, Botticelli (who depicted more than one hundred botanical species in his Primavera), Matisse, Morandi, alongside contemporaries like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Kehinde Wiley, Hurvin Anderson, Nicole Eisenman as part of her “painting family.” She is as aware of traditional portraiture and still-life, the memento mori, as she is of a painterly preoccupation with how to convey sensuality, the life of objects, the desire of the eye to not only see, but touch, caress, feel. As the title of the show, a reference to the book of Ecclesiastes, suggests: “the eye is not satisfied with seeing.” Painting is a process of representation, but also of grief, of love, of paying attention, of reckoning, of something wordless and inchoate: “a beloved practice,” the artist says, “but also this grieving process for something that was and won’t be again.” A process that likewise brings Packer back to queries of a different, practical, medium-specific variety: “Such as what the fuck is a good painting?” I think Packer knows, though I am sure she will never stop questioning.

Emily LaBarge is a writer based in London, where she teaches at the Royal College of Art. She has written for Artforum, Bookforum, frieze, the White Review, Granta, and the Paris Review, among other publications. She is the London correspondent for the Montreal-based quarterly, esse arts + opinions.