Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge

The Vietnamese artist weaves a parafiction of the Mekong Delta.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019, installation view. Image courtesy Chisenhale Gallery and the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

Thao Nguyen Phan: Becoming Alluvium, curated by Ellen Greig with

Amy Jones, Chisenhale Gallery, 64 Chisenhale Road, London, through December 6, 2020

• • •

It is increasingly difficult to believe that human beings possess the ability to grasp principles of cause and effect. Or perhaps they—let’s say we—simply don’t care, preferring to highlight the benefits of “progress” and “development,” happily turning blind eyes as species disappear and ecologists warn of one pandemic as the beginning of many to come. Or perhaps we have yet to truly understand consequences as lasting and irreversible, though the evidence is abundant. But has it always been so? What is the cost of our collective ignorance, both globally and locally? Most critically, is it too late to turn back? Can we still effect meaningful change?

These are among the many questions subtly, sensitively posed in Thao Nguyen Phan’s Becoming Alluvium, the Vietnamese artist’s first solo exhibition in a UK institution. At Chisenhale Gallery, her most recent moving-image work is shown alongside an ongoing series of paintings. “Why did the stream dry up?” an unknown interlocutor asks early in the titular video (2019), white subtitles against a scene of placid, silt-tinged aquamarine, slowly spurred to widening ripples as a wooden boat revs its spluttering engine and cuts through the water, heading somewhere into the blue beyond. The narration supplies its own rejoinder: “I put a dam across it to have it for my use, that is why the stream dried up.” Another question, another answer: “Why did the harp-string break? / I tried to force a note that was beyond its power, that is why the harp-string is broken.” These lines come from poem 52 of Rabindranath Tagore’s The Gardener (1913), a cycle of love verses used here to invoke the subject of Phan’s quiet paean: the Mekong Delta, whose seven branching waterways have for decades been disrupted by invasive and sometimes disastrous damming, and which, from above, might in fact resemble a striation of strings. (Deltas are so named for their triangular shape, like the Greek letter, an appellation shared with certain varieties of harps.)

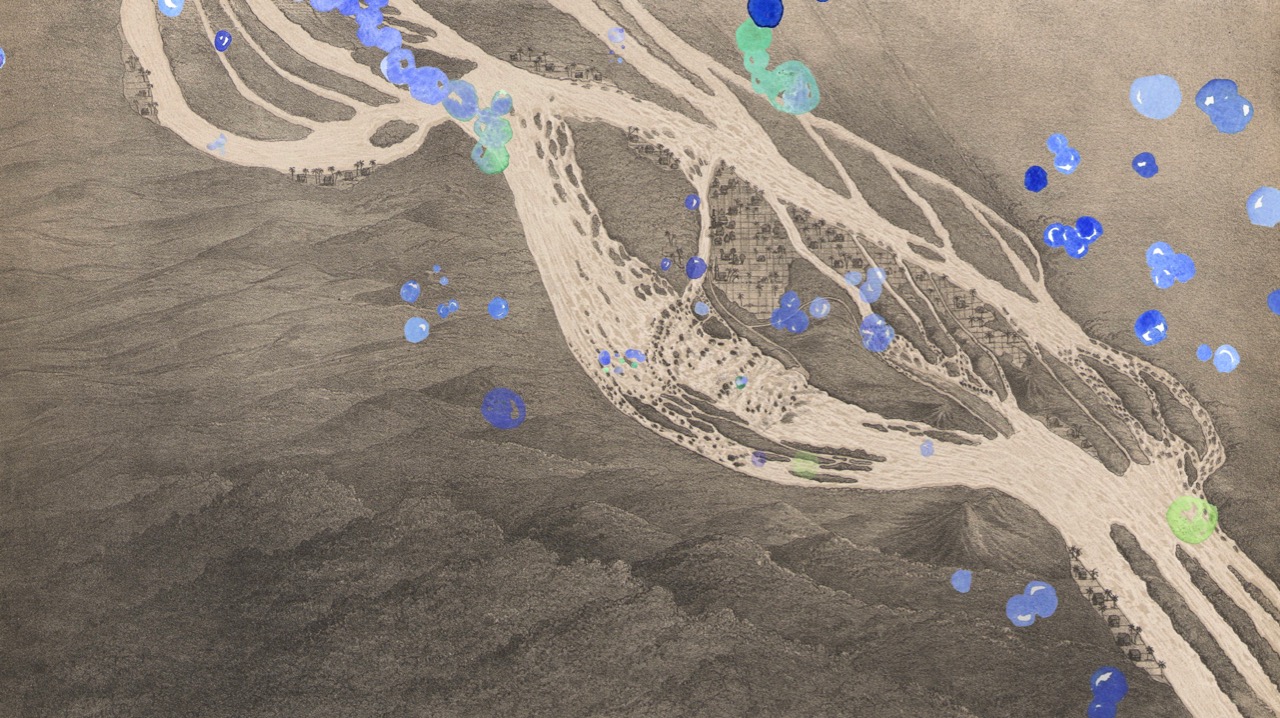

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019 (still). Image courtesy Chisenhale Gallery and the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

The Mekong Delta is the ancient ecological melody at the heart of Vietnam, carrying alluvium—a rich mineral that produces fertile soil for agriculture—from up to downstream, then out into the East Vietnam Sea. Tagore is the first of many voices Phan calls on to weave a parafiction of the region past, present, imagined: a work—“moving images,” as she terms her videos—in which magic, literature, legend, and spiritual belief are lyrically twined with documentary, historical account, and archival artifact. The story, although it is of the ilk with neither beginning nor end, commences with two brothers who are drowned when a hydroelectric dam ruptures, flooding their village. This is a reference to the 2018 breaking of Saddle Dam D in southeast Laos, which killed up to 1,100 people and displaced 6,600 others; but the siblings in Phan’s Becoming Alluvium are given new life after their bodies come to rest in the still, algous waters near their home: “The river commemorates the poor souls of its children / with a cascade of reincarnations,” the video’s text tells us.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019, installation view. Image courtesy Chisenhale Gallery and the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

The elder brother becomes the Irrawaddy dolphin, while the younger takes the form of the water hyacinth, both associated with the Mekong, the site to which these souls in flux will be forever wed: “their maternal mother, and their greatest enemy.” Together, the mammal and flower vow “to save more sentient beings in this life,” then share their memories of many lives past, a series of three rebirths that structure the remainder of the work. In the first, footage of daily ferry crossings—the wide, shining waters of the Delta in daylight, its wind farms and cool indigo blues in twilight—are overlaid with passages from Marguerite Duras’s The Lover (1984), in which the narrator recalls the hot, monotonous seasons of her childhood in French Indochina and its rivers that “flow as fast as if the earth sloped downward.” The second incarnation brings us to markets and sites of leisure along the river, as well as its shores covered in mountains of man-made detritus, this time accompanied by passages from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1972) that recount the city of Leonia and its obsession with new material objects, as if to discard and expel is to cleanse itself of “a recurrent impurity.”

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019, installation view. Image courtesy Chisenhale Gallery and the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

The final incarnation telescopes into the past, overlaying engravings from a French colonial expedition with watercolor animations that tell the Khmer folktale of a princess who wished for a necklace made from drops of monsoon dew. She is drawn as eerily headless, like so many of the purloined Southeast Asian statues Phan came across in Paris’s Musée Guimet; and heedless, too, as she ultimately realizes the folly of her vain desires and is transformed into water that cycles through the Mekong. Drops of dew collected make only a meaningless pool.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019, installation view. Image courtesy Chisenhale Gallery and the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

Phan has spoken of using her work to redress the vision of “Vietnam” dominated by twenty-first-century conflict, turning to older, richer, but no less complex sources that speak of a different country with many histories, from French colonialism, to Japanese occupation, to current Communist state rule. Becoming Alluvium, with its lilting poetic-philosophic acts of storytelling both personal and collective, serves as a quiet national critique at once imperialist, contemporary, and ecological. Stories and official narratives, like bodies and beings, are reincarnated time and again, and we forget this—take them for finite truths—at our peril. Phan’s siblings gesture at the karmic potential of “do no harm” to begin to limit inherited generational trauma and future generational damage. The artist notes that so-called “third-world” countries like Vietnam, though most affected by it, are less likely to speak about climate change than their Western counterparts. They seek, instead, productive industrial narratives of a “brighter, better” future, in spite of the detrimental long-term impact of invasive processes—sand mining, damming, polluting, overfishing—on the resources that sustain Vietnamese agriculture, as well as its local communities.

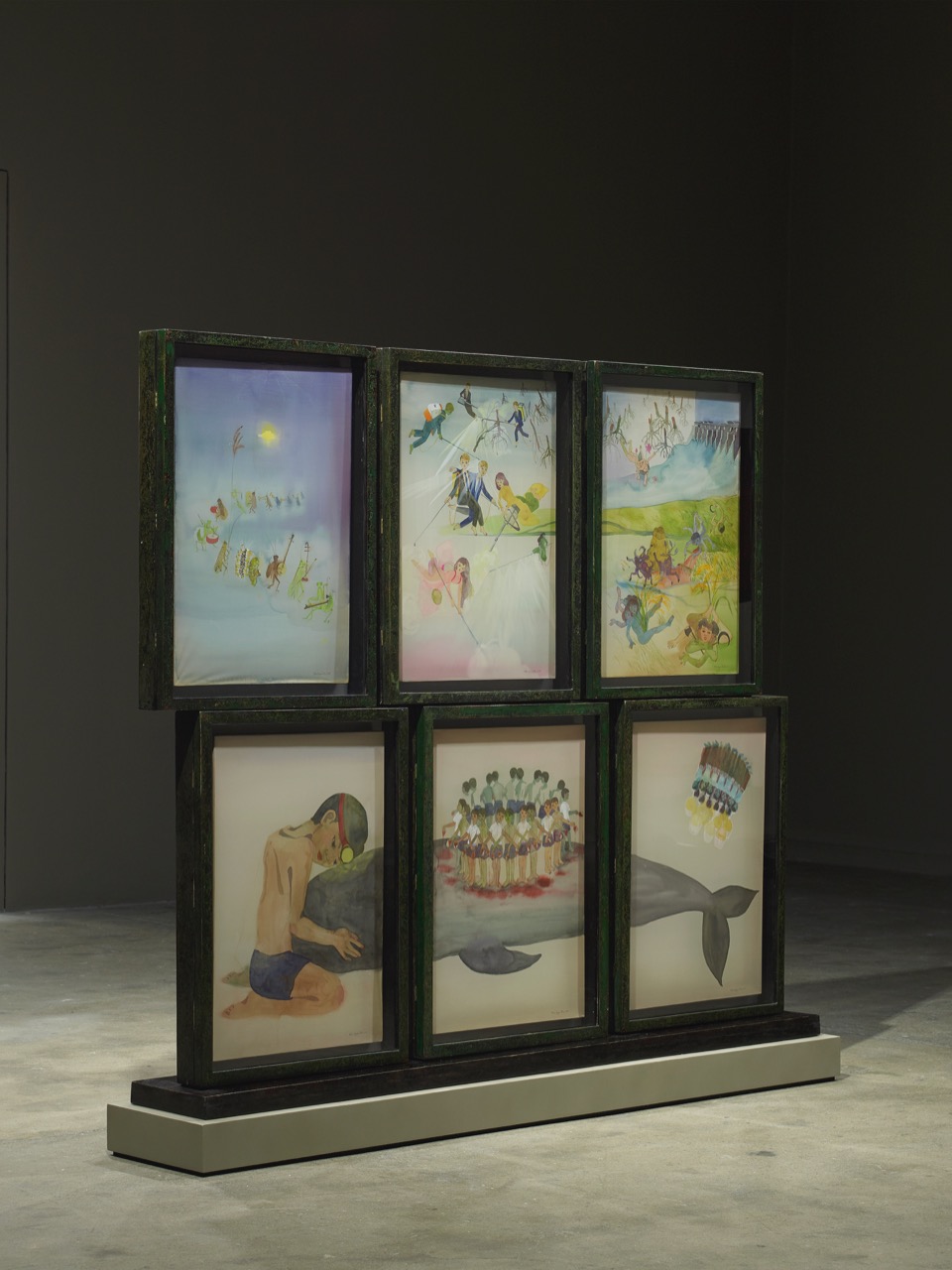

Thao Nguyen Phan, Perpetual Brightness, 2019–20, installation view. Image courtesy Chisenhale Gallery and the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

Phan’s hope for brightness is, rather, something that shines even when the light is low, glimmers and flickers in dimness, its own source of enduring radiance. In Perpetual Brightness (2019–20), a series of six panels joined as a freestanding screen, watercolor-on-silk paintings depict fantastical, almost Henry Dargeresque scenes in which children fly through the sky with pesticide sprayers, engage in mourning rituals of pouring red wine over a dead dolphin, contort their bodies, grow extra limbs, sprout vegetation from their genitals. The frames for these paintings—produced in collaboration with Phan’s husband, the artist Truong Cong Tung—are as important as the paintings they house. Made from lacquer on wood, one of the highest traditional Vietnamese arts, the backs of the frames are inlaid with eggshell and silver leaf that form an abstracted image of the Mekong Delta—flecked streams of incandescent white against the muted brown and green pigments produced by natural dyes.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Perpetual Brightness, 2019–20, installation view. Image courtesy Chisenhale Gallery and the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

Lacquer painting can only dry in a humid environment, after which the paint is sanded away under running water to reveal the layering of paint beneath—not unlike the Mekong’s purifying alluvium, which washes away impurities. The artist has referred to Becoming Alluvium as her “humble Gitanjali” to the Mekong, Gitanjali meaning song offering, devotional in Bengali—another nod to Tagore, the motto of whose own Nobel-winning Gitanjali (1910) is, “I am here to sing thee songs.” We cannot change the past, no, but we can make from it something new—something that poses questions about cause and effect and consequence, not only to prompt answers, but to point to the future, some of which is still in our hands.

Emily LaBarge is a writer based in London, where she teaches at the Royal College of Art. She has written for Artforum, Bookforum, frieze, the White Review, Granta, and the Paris Review, among other publications. She is the London correspondent for the Montreal-based quarterly, esse arts + opinions.