Reinaldo Laddaga

Reinaldo Laddaga

In the Argentine’s work, an art of transformations.

Marcia Schvartz: Works, 1976–2018, installation view. Courtesy the artist and 55 Walker (Bortolami, kaufmann repetto, and Andrew Kreps Gallery). Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

Marcia Schvartz: Works, 1976–2018, 55 Walker (Bortolami, kaufmann repetto, and Andrew Kreps Gallery), 55 Walker Street, New York City, through September 7, 2021

• • •

Marcia Schvartz is one of the best-kept secrets of Latin American art. Not for Argentines, though: for almost half a century—the earliest works in an excellent survey now in view in New York City date back to the 1970s—she has been a central protagonist in the art scene of her homeland. Over the years, indifferent to trends and fashions, she has stubbornly worked in the classical forms of figurative painting, drawing, and sculpture, convinced that oil, charcoal, tar, pastel, and all the rest offer an obstinate resistance to the maker’s designs, and that, through the confrontation between designs and materials, unpredictable, ungoverned images emerge.

Marcia Schvartz: Works, 1976–2018, installation view. Courtesy the artist and 55 Walker (Bortolami, kaufmann repetto, and Andrew Kreps Gallery). Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

Confrontations take place all the time in the work of this artist, who was born in Buenos Aires in 1956 and two decades later underwent the experiences of leftist radicalization and—following the military coup of 1976—European exile that were common to many of her generation. She returned to her country with the reinstatement of democracy in 1983 and participated in the extraordinary cultural ferment of Argentina in the mid-1980s, which was brutally interrupted by the AIDS crisis. Egon Schiele was a cult figure among artists in Argentina at that time. The schematic angularity of the Austrian painter, whose lines can be like quick and angry cuts, is very much present in the portraits that make up a substantial part of this show, especially in a series using pastel, charcoal, and touches of oil on linen or burlap. Desnuda y con zoquetes (Nude with Socks), the largest and most impressive of these pieces, portrays a woman in full frontal nudity reclining over pillows on a bed or divan, in obvious reference to Manet’s Olympia, with the shoes replaced by pink socks. The drapery in Manet’s background is absent; instead Shvartz shows us the bare canvas, as Schiele did in his self-portraits depicting masturbation, which—with its frank display of the subject’s genitals—the painting also echoes.

Marcia Schvartz, Desnuda y con zoquetes (Nude with socks), 2012. Oil pastel on linen, 70.8 × 62.9 inches. Courtesy the artist and 55 Walker (Bortolami, kaufmann repetto, and Andrew Kreps Gallery). Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

Schvartz’s work shows us not essences but transformations. This is true of her portraits and even more so of her allegorical images. Consider one on view, Ensueño (Daydream), which presents a seemingly female figure in a coastal landscape. The general air of the environment together with the appearance of this either Native or mestizo figure conjure—at least to we who know it—a specific region: the so-called Litoral, an area of rivers, lagoons, and marshlands that spans the northeast of Argentina, the south of Brazil, and most of Paraguay. Like Schvartz’s art, folk literature of the Litoral depicts an animistic universe that is not populated by distinct and rigidly bounded creatures but by entities subjected to constant interpenetrations and metamorphoses.

Marcia Schvartz, Ensueño (Daydream), 1992. Oil on canvas, 59 × 70.8 inches. Courtesy the artist and 55 Walker (Bortolami, kaufmann repetto, and Andrew Kreps Gallery). Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

At first, the scene in Daydream seems paradisiacal, but it doesn’t take long to mutate under our gaze into something much more disturbing. Because the woman’s outstretched hair is braided with the ropes of a hammock it’s hard not to feel that we are contemplating a session less of repose than of torture. The impression of violence is reinforced by the livid purple hue of her legs. But her lips, which press against her own arm, seem to suggest that she is kissing or licking herself, immersed in an autoerotic ecstasy whose intensity is echoed by the ample waves of sunshine, sand, clouds, sky, and water that are woven together in the shadow of palm trees whose leaves evoke fingernails.

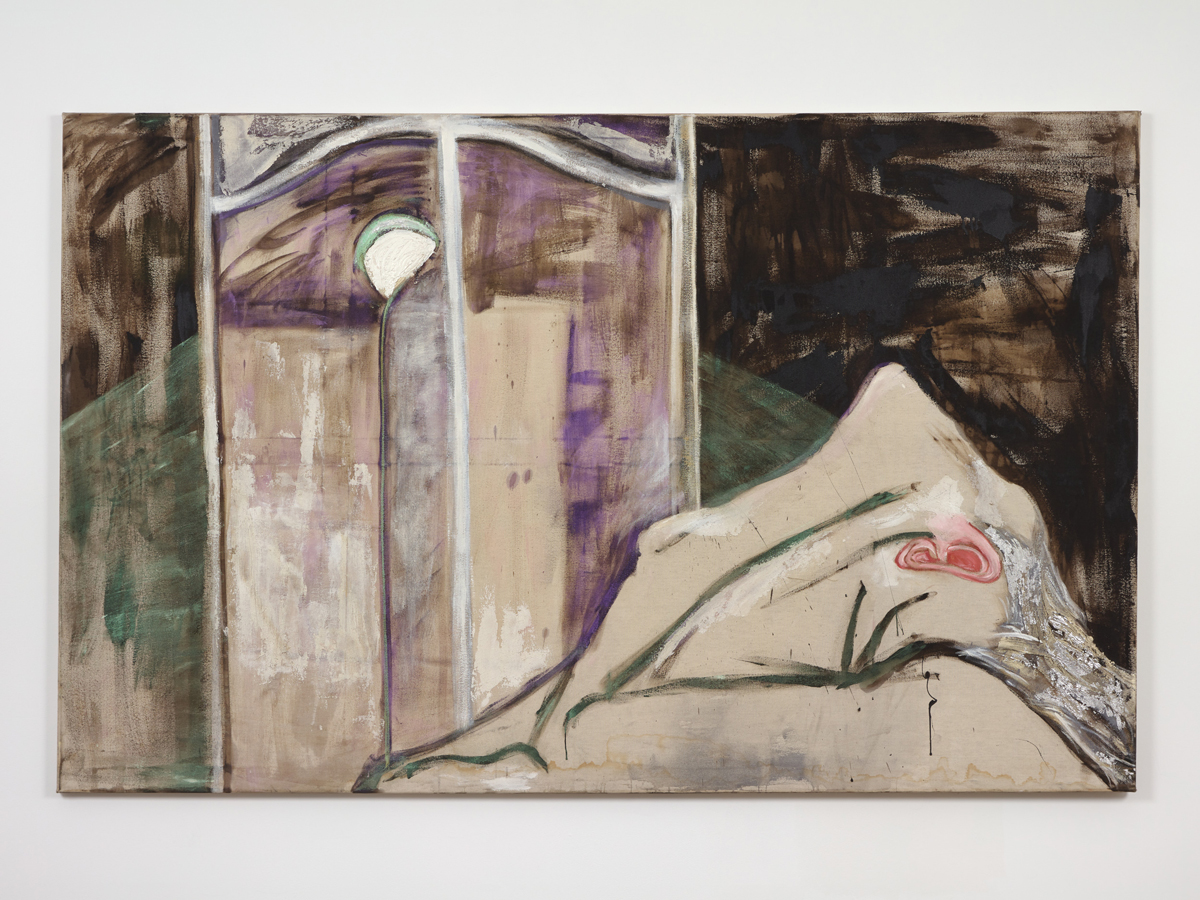

Marcia Schvartz, Luciérnaga furiosa (Raging Firefly), 2000. Mixed media on canvas, 98.4 × 55.1 inches. Courtesy the artist and 55 Walker (Bortolami, kaufmann repetto, and Andrew Kreps Gallery). Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

The more we look, the more the image oscillates. Neither our eyes nor our mind can find a stable resting point. The silent screaming never stops. It keeps going in the most radiant pictures as well as in the most opaque, like Luciérnaga furiosa (Furious Firefly). This splendid work from 2000 depicts a scene taking place in an uncertain space. An insectoid figure with a white rounded head—like a firefly at night—hovers behind what looks like a skeletal window. Perhaps it is watching a second humanoid figure in the foreground, who arches his or her head back in ecstasy, pain, or languor. We can’t see the face, which looks away from us, but a detailed fragment on the top of the neck emphatically stands out. We might initially think it’s an earlobe; a second glance tells us that this rose-tinted detail might also be a—slightly porcine—nose. We are forced to vacillate between one interpretation and another, as happens in front of those optical illusions where a painted vase unceasingly turns into a human profile.

Marcia Schvartz, Erinia (el misterio del arte) (Erinyes (the mystery of Art)), 2003. Mixed media on canvas, 63 × 71 inches. Courtesy the artist and 55 Walker (Bortolami, kaufmann repetto, and Andrew Kreps Gallery). Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

The title of Schvartz’s painting was obtained by changing one letter in a lyric of the classic tango “El día que me quieras” (The day you love me), which has been recorded by hundreds of singers, from Carlos Gardel to Plácido Domingo. A lover describes to his beloved the day when she will finally adore him. That night, they will walk as in a trance through a forest or garden; the stars will look over them as they pass, “and a mysterious ray will nest in your hair, curious firefly (luciérnaga curiosa) that will see . . . that you are my solace . . .” The oneiric atmosphere of this tableau is present in the painting, but the firefly is no longer curious; it is furious—not playful but menacing. We suspect that in Schvartz’s adaptation of “El día que me quieras,” the “mysterious ray” won’t nest on the head of the beloved. Rather, it will sink into it just like the claws of a black-winged Erinys, howling to a turbulent sky, plunge into the neck of her victim in a painting from 2003 that hangs on a contiguous wall. The Erinyes, dark and wise daughters of the Night and sisters of Aphrodite in the Greek pantheon, were vengeful deities. Their name may have come from the word eris (confrontation) and their alternative denomination—the Furies— could have been a perfect title for Marcia Schvart’s show.

Reinaldo Laddaga is an Argentine writer based in New York. The author of numerous books of narrative and criticism, he taught for many years in the Romance Language Department of the University of Pennsylvania. His latest books are Los hombres de Rusia (The Men from Russia), a novel, and a forthcoming book about walking in New York at the height of the COVID crisis.