Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

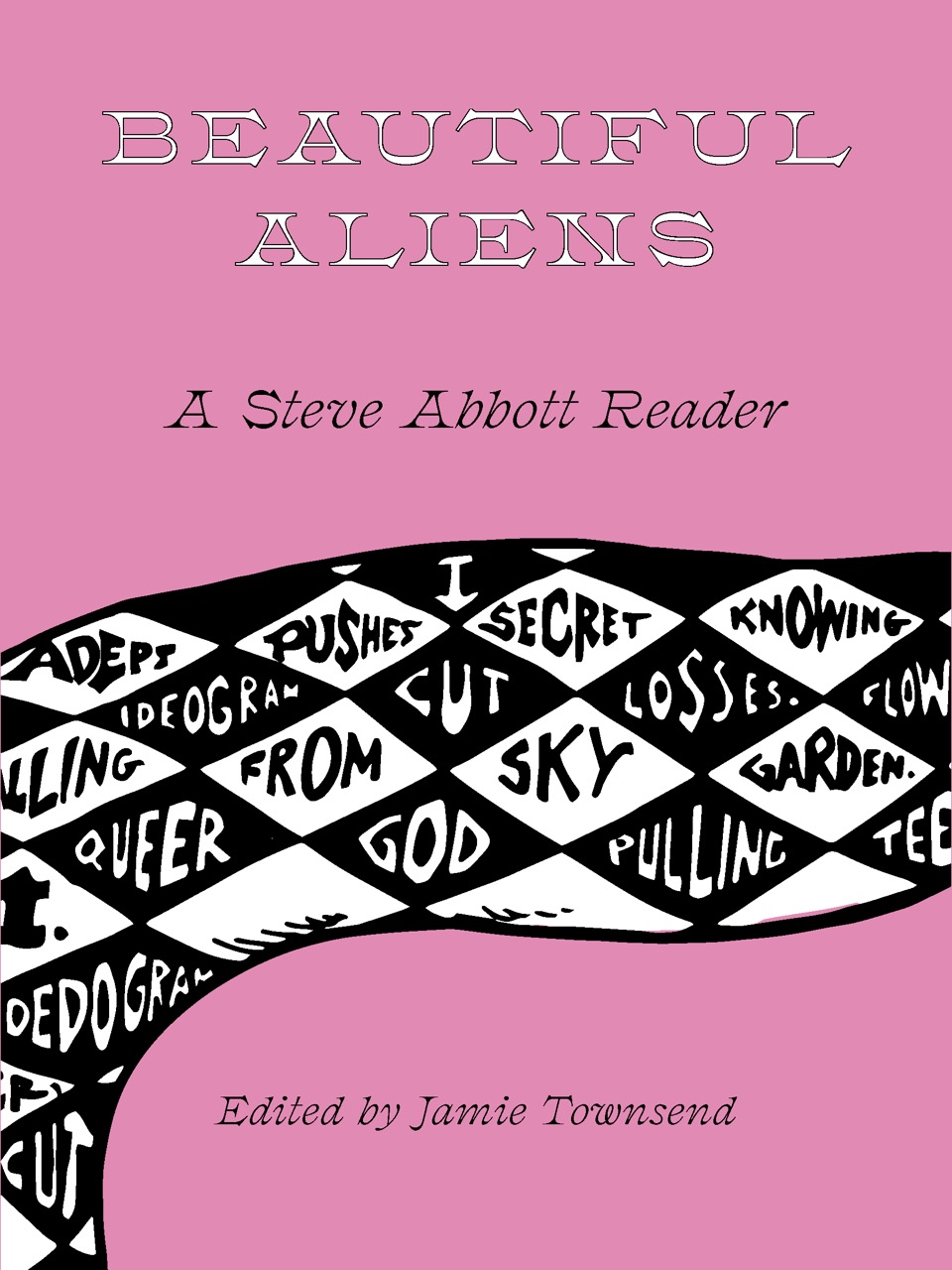

“Open these flowers or beware”: a collection of work by the writer

Steve Abbott.

Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader, edited by Jamie Townsend, Nightboat Books, 324 pages, $21.95

• • •

“To be honest,” Steve Abbott writes in a previously unpublished essay from the 1980s, “I think we must admit that transgressive eroticism constitutes the very essence of gay life (or at least did before AIDS).” I underlined this sentence in my copy of Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader, not because it’s news to me, but because it crystallizes much of what Abbott’s work is about. There’s the casual style, the self-reflective theorizing, the elegiac parenthetical abutting glimpses of halcyon queerness. Whatever his genre—prose, poetry, or comics—Abbott wrote from the margins, a position inseparable from his own queerness, and one that gave political and moral credence to his work. As one of the key figures of New Narrative, he was at the center of a West Coast literary uprising that saw little distinction between writing and socializing; both connect the messy lone consciousness to the rest of the world.

Abbott is the consummate cult writer. His books—Wrecked Hearts (1978), Stretching the Agape Bra (1980), Lives of the Poets (1987), Holy Terror (1989), and the posthumous The Lizard Club (1993), among others—are mostly out of print. He’s arguably better remembered as the impresario of Bay Area underground literature than as an artist himself. The writers Kevin Killian and Dodie Bellamy described him as the “sparkplug that every scene depends on without, perhaps, realizing just how much it needs him.” He edited the venerable Poetry Flash newsletter; organized literary conferences; named and publicized the New Narrative movement; produced the short-lived but legendary SOUP magazine; and published, nurtured, promoted, or otherwise buoyed the careers of Killian, Bellamy, Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Aaron Shurin, Sam D’Allesandro—the list goes on. Abbott died of AIDS-related complications in 1992, at age forty-nine.

Lately, he’s probably better known as the subject of Fairyland, his daughter Alysia Abbott’s 2013 memoir. As a single father in Gay Liberation–era San Francisco (his wife died in a car accident in 1973), Abbott was a kind of bohemian homemaker who took inspiration from both the comforts and confinement of family life. “The Departure,” a poem included in Beautiful Aliens, finds him playing tooth fairy; another poem concludes with an idle night of TV dinners and flipping through Newsweek. He weaves snippets of Alysia’s childhood conversation into his work: “Why is the moon following us?”; “open these flowers or beware.” In the poem “It’s a Strange Day Alysia Says, a Green,” Abbott mentions the “creative regimen of poverty”—surely one of the few examples in American literature from that period of a single father, gay or not, registering the interplay of economics, parenting, and artmaking.

New Narrative thrived on this fusion of memoir and politics. Robert Glück, one of the movement’s architects, thought of autobiography as “daydreams, nightdreams, the act of writing, the relationship to the reader, the meeting of flesh and culture, the self as collaboration, the self as disintegration, the gaps, inconsistencies and distortions, the enjambments of power, family, history and language.” Abbott’s work—with its ambient “I,” its real-life references, its sex and gossip, its constant code-switching between high and low, its occasional metafictional conceits—exemplifies the New Narrative playbook. In his essay “Notes on Boundaries: New Narrative,” also included in this volume, Abbott describes one of the movement’s hallmarks as mutual vulnerability between reader and writer, brokered by the text’s continual self-disclosures. “Lured into the writer’s real life story (actually, a tangle of stories within stories), readers have to compare to and create their own narrative,” he suggests.

That strategy is most evident in Abbott’s poetry and fiction. That work is playful and often cerebral, but the biggest revelation in Beautiful Aliens is his essays. The subjects alone indicate the breadth of Abbott’s interests: phone sex in the age of AIDS, the avant-garde composer and performer Diamanda Galás, queer romance, decadent art, the expressive vocabulary of faces. As a critic, he’s ruthless and generous and witty—sometimes all in the same sentence, as when he contrasts the work of David Leavitt, the darling of insipid ’80s gay fiction, and Dennis Cooper, whose novels toggle between sadomasochistic violence and tender encomiums to characters’ assholes: “If Leavitt’s like a page torn out of Dynasty, Cooper’s more a mixture of Miami Vice, the old Saturday Night Live, and Printer’s Devils.” (The latter is a 1982 gay porn directed by William Higgins.) Abbott has a knack for critiquing artists by comparing them to pop-culture flotsam. Here he is on Armistead Maupin: “Serialized in a daily newspaper, Maupin’s stories delight for the same reason Herb Caen or a soap opera does. In the space between episodes, I can fill in the character’s lack of depth with the emotions of my own life.”

As one expects from New Narrative, Abbott’s essays are also autobiographical. He begins the aforementioned review of Maupin by recalling that he arrived in San Francisco as a “gay immigrant” from Atlanta in 1974, the same year Maupin came out of the closet, and two years before Tales of the City began appearing in the San Francisco Chronicle. Whereas Abbott was sobered by the ensuing decade of terrorism, fascism, AIDS, religious hypocrisy, and political entropy, Maupin’s work stalled in a “Never-Never Land of childhood” and “ ’70s nostalgia,” Abbott argues, in which differences of race, class, and sex evaporated into a thermal haze of gay camaraderie. “How can I care about people whose connection to life is so persistently trendy, minimal, and vapid?” Abbott writes.

Abbott’s literary heroes—and the subjects of various essays in Beautiful Aliens—are more unconventional: the Beat poet Bob Kaufman, in whose antic style and anti-careerist stance Abbott saw echoes of his own role as “visionary outcast”; radical debauchees like Georges Bataille, William S. Burroughs, and Jean Genet; and the poet John Wieners, whom Michael Rumaker described as an “old invisible fag” besieged by addiction and psychiatric lockups. “I try to write the most embarrassing thing I can think of,” Wieners once told his editor—a credo that could be the flipside of a line from Abbott’s poem “Elegy”: “What seems most outlandish in our autobiography is what really happened.”

Abbott’s work doesn’t slot neatly into genres or thematic pigeonholes. It’s one indivisible but porous project coterminous with his life. The sui generis Lives of the Poets, for example, mixes capsule biographies of famous writers with quotes attributed to Lady Murasaki and Jane Goodall, along with Abbott’s own diaristic observations. There’s no separation between fact and fiction, fiction and memoir, Abbott as writer and Abbott as subject. The text exists in an intimate, permanent now.

In an essay titled “Will We Survive the 80’s,” Abbott writes, “It’s a simple fact that someday all of us will die. Maybe our entire planet will. But I also know, more deeply than ever, that our lives, our culture and our world are too beautiful to throw away.” The queer ethos and queer fellowship of Abbott’s world feels almost utopian in 2019, despite his heartbreak, his disgust with consumerism, his outrage at the status quo. I don’t mean utopian in the trite sense of Maupin and his marzipan San Francisco. I mean utopian in the sense of opposition—to cowardice, to ignorance, to banality, to death. Abbott’s utopia was precious and couldn’t possibly last. Utopia never does.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.