Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In snake skin, the tricky quest for meaningful transformation.

Baseera Khan: snake skin, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Simone Subal Gallery. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Baseera Khan: snake skin, Simone Subal Gallery, 131 Bowery, New York City, through December 22, 2019

• • •

The Muslim-American artist Baseera Khan, born in Texas to undocumented parents who traveled from India to raise their family in the United States, has long sought in her performances, sculptures, installations, and deft use of readymades to explore the complications of articulating an identity that is understood by many as irretrievably other, no matter where she turns. snake skin, her first solo outing at Simone Subal Gallery, comes two years after her breakthrough 2017 exhibition iamuslima at Participant, Inc., which segued into an extremely prolific period of working and showing for the artist. With the new pieces on view here, all of which were made in 2019, Khan continues her study of the ways that people must fit themselves into inhospitable structures—cultures, languages, aesthetic forms, and architecture itself—sometimes by wrapping themselves tightly around what will not let them in, sometimes by shedding what does not serve them. But if in earlier work she honed in on American pop culture, fashion, the strictures of Islam, the authority of the state, and so on, here she turns her critical lens as well toward modes of resistance and subversion themselves, revealing them to be imperfect tools—necessary, but also provisional, vexed, and as unwelcoming to some as the structures they’re trying to oppose.

The centerpiece of the installation is a series of seven slices of a Corinthian column, each six feet in diameter and fashioned from rigid foam insulation, plywood, and resin dye panels, so light that they can be moved around with relative ease (Column 1–7). If they were stacked one atop the other, like one of the ancient forms that they replicate, they would stretch fourteen feet high, but here some are piled up while others collapse on the floor or are propped on their sides. The classical column is an architectural element that conveys the enduring power of Western Civilization, and is still ubiquitous in our contemporary landscape (as conveniently demonstrated by the columns on the façade of the building across the street from the gallery, visible through the large windows).

Baseera Khan, Column 3, 2019. Pink Panther foamular, plywood, resin dye, custom handmade silk rugs made in Kashmir, India, 72 × 22 × 72 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Simone Subal Gallery. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Though laid low in Khan’s refashioning, these pillars are not ruins so much as reclamations, thanks to the skin that’s been applied to their surfaces—handwoven Kashmiri rugs, collaged together so that their geometries and palettes clash and morph as they wind their way around their supports. The wrapping reflects a common practice in mosques, where carpets are used to obscure the architecture of repurposed buildings, including columns—a process of claiming space that attempts to leave behind what came before, a form of renewal that is also a veiling of the past. (These acts of architectural détournement are sometimes dramatic, as with the Masjid Malcolm Shabazz in Harlem, which was originally built as a casino and which Khan cites as a reference.) The carpets were commissioned by the artist from Kashmiri artisans, with whom she worked closely to achieve her designs; after India’s deeply anti-Islamic Modi government rescinded Kashmir’s status as an autonomous territory in August, putting the region’s Muslim population under a strict curfew, closing borders, and imposing a media blackout, the weavings had to be smuggled out—a covert operation, art as contraband.

Baseera Khan: snake skin, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Simone Subal Gallery. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

The repurposing of these columns is treated by Khan as a metaphor for the ability of immigrants to make space for themselves by creative, even veiled, ingenuity, and simultaneously for the ways in which the toppling of one form of authority is often just replaced by another, so that any act of resistance is by nature an unfinished project. At the foot of the stacked slabs lies a small chunk of carpet-wrapped foam—a remnant of a destructive act Khan has visited on her sculptures wherein she carved away the fluting, leaving rough, striated gouges in her wake. This bit of detritus functions as a kind of conceptual key for the installation, suggesting a flake of reptilian shed skin—if one rejects both Western cultural power and that of Islam, another form of repression will simply grow back to replace them.

Baseera Khan: snake skin, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and Simone Subal Gallery. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

The rest of the show, consisting of eight framed prints and an audio piece, similarly asks us to think about the slippery nature of the quest to achieve a meaningful and enduring transformation. On the hour, an adhan—the Muslim call to prayer—rings out in the gallery. But instead of a male muezzin intoning a statement of faith, we hear Khan’s sweet, plaintive, decidedly feminine voice singing the classic 1984 song by the Smiths, “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want.” Khan subverts the gendered constraints often associated with Islam, but does so by underlining the fact that Western pop culture is no deliverance: with its opening line “Good time for a change,” the song may have seemed like a plea for renewal when it came out in the Thatcher era, but it sounds awfully different now that the band’s angsty lead singer Morrissey has revealed himself as a supporter of right-wing, Islamophobic political parties and causes.

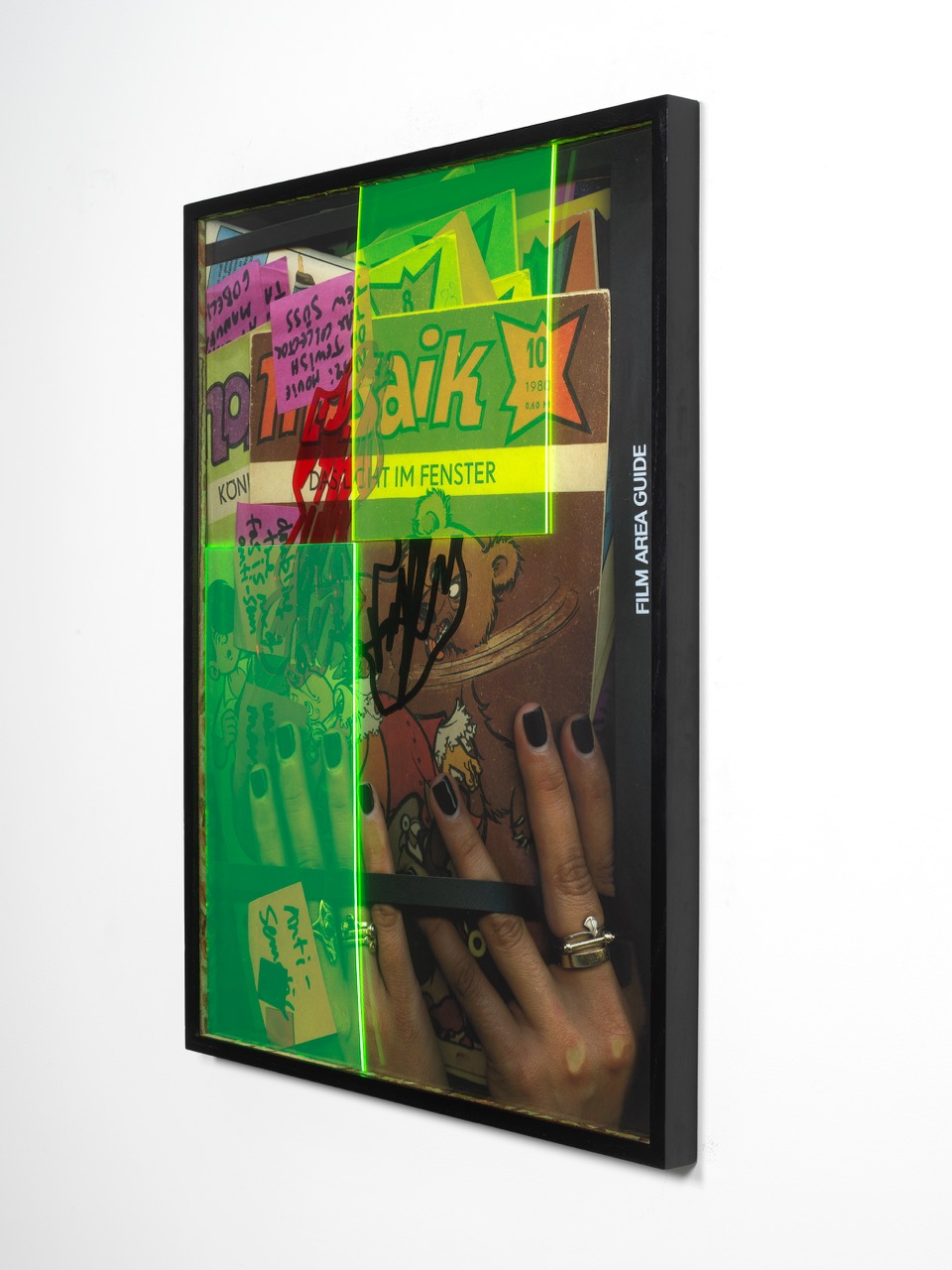

Baseera Khan, Redacted Frame, 2019. Acrylic, chromatic prints, custom handmade silk rug pieces made in Kashmir, India, 41 1/4 × 31 1/4 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Simone Subal Gallery. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Likewise, the framed collages lining the walls of the gallery refer to the endlessly renewing nature of power, and the constant need to resist—even when that power is wielded by our comrades. To make them, Khan amassed photocopies, books and magazines, and a variety of objects including commercial photo frames, neon sticky notes, and scissors, and placed them on a scanner bed; her own ring-laden hands are often visible resting on the glass. She then overlaid the resulting prints with neon-colored, calligraphic, acrylic cutouts, and framed it all using bits of embroidered carpet as spacers. Her source images are largely drawn from a hugely popular East German comic book series called Mosaik, which began publication in 1955. (The color palette of the Mosaik pages are, if you look closely, precisely echoed in the Kashmiri rugs found elsewhere.) While Mosaik was tolerated by the GDR authorities, who saw it as Disney-esque without the capitalist exploitation attached, its light-hearted narratives of international adventures contained subtle and subversive jabs at the state; some scholars believe it contributed to the fall of the Berlin Wall. But for all the comic book’s stealthy political agenda, Khan is acutely aware of its blind spots: its pages are filled with anti-Semitic and racist caricatures, which the artist “redacts” by placing the semi-transparent acrylic scribbles on top, or screen-printing scribbles over them.

Baseera Khan, Baarwaada, the Oldest Walk, 2019. Acrylic, chromatic prints, custom handmade silk rug pieces made in Kashmir, India, 31 × 25 1/4 inches.

In these prints, Khan juxtaposes the cartoons with other images—views of a devastated mosque, some tumbled Roman columns, handwritten pink Post-it notes, marked-up pages from Arundhati Roy’s The End of Imagination, and so on. While Roy’s pages, visible in the panel Censored Hands, speak of the rise of violence against India’s Muslim minority under Modi’s rule, first as chief minister of Gujarat and then as prime minister of the whole country, Khan is careful to have chosen for two other works (Baarwaada, the Oldest Walk and 27 Jain) images, on the one hand, of one of the world’s longest extant mosques, sited in Gujarat and now in a grave state of disrepair, and on the other, the Quwwat ul-Islam mosque in Delhi. The former survives against the odds, while the latter was built on top of, and at the expense of, twenty-seven Jain temples—an act of cultural assertion that is simultaneously an act of erasure. There is no uncomplicated innocence to be found here, no form—yet—of liberation that makes everybody free.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her book Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is editor of the forthcoming Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2019), and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.