Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

Kate Zambreno delves into a dying French writer and the

problem of friendship.

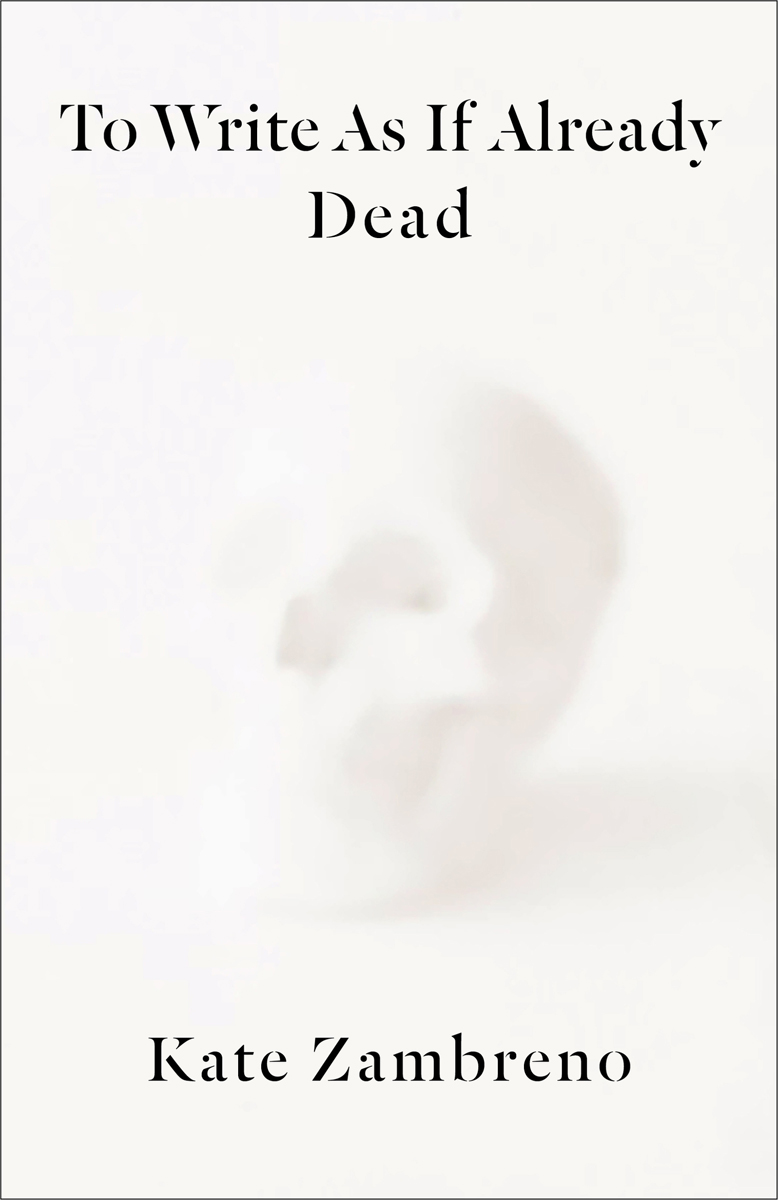

To Write As If Already Dead, by Kate Zambreno, Columbia University Press, 157 pages, $18

• • •

As he was dying of AIDS-related illnesses in the Paris suburbs in the fall of 1991, the young French novelist Hervé Guibert kept a hospital diary that has since become a minor classic of literature about the medicalized body. Throughout his slim volume (published in English as Cytomegalovirus: A Hospitalization Diary), Guibert asserts the dignity of those who are ill and enacts a temporal and philosophical aesthetic calibrated to his impending death. “Today, I may have made the acquaintance of the room in which I will die. I don’t like it yet,” he wrote that September, about three months before he did die, at age thirty-six. That yet—it breaks your heart. Fatalism pervades all of Guibert’s late work, but so does its counterweight. In his pages, the dying come to sanctify their obsolescence and even concede beauty in their newly circumscribed world.

In To Write As If Already Dead, the novelist and essayist Kate Zambreno transports Guibert’s themes to a contemporary American setting. Her book is divided into two parts. The first is a roman à clef that harries “the problem of a friendship”—namely, Zambreno’s epistolary relationship with a literary blogger who later goes permanently offline. The eponymous second half is Zambreno’s attempt to write a study of Guibert’s seminal novel To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990), itself an AIDS-haunted roman à clef about the problem of a friendship. The two sections dramatize Zambreno’s burden as a mother trying to summon the time and energy to write—a body, in other words, tasked with caring for another body. (“I have at most fifteen minutes to write this passage,” she confides at one point. “This passage will not be great literature.”) The two sections also share an ambient style: dilatory, discursive, cerebral, a style much like Guibert’s own, and one that mimics the roving, piecemeal consciousness of the bedridden.

Zambreno and Guibert are perhaps an odd couple. Where the latter wrote unabashedly of cruising and gay sex in a milieu that included Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes, Zambreno writes here of motherhood, adjunct teaching, and life in Brooklyn. She’s aware of the dissonance. “I would never have been included in Foucault’s circle,” she writes. “I am a mom on a couch!” Yet, one of the pleasures of her book is the affinities she traces between herself and Guibert. Among these are bodily depredations—AIDS for him, shingles and pregnancy for her—and, later, the paranoia and estrangement wrought by two different pandemics. The writers’ parallel literary techniques are also elegant rebuttals to a common precarity. Describing Guibert’s diminished stamina, Zambreno could just as well be annotating her own method: “A work that accumulates out of an exhausted life, out of the narrative momentum of survival energy, is by its nature fragmented, coming in starts and stops, manifested out of any available time.”

The book is a riposte, however incidental, to current critical dogma in which outsiders are presumed to lack the authority to write across difference. Zambreno worries that she’s “not cosmopolitan enough or queer enough” to reckon with Guibert. It hardly matters. While she doesn’t exhibit Guibert’s ravening lust, she has some of his acidity, his charisma, his meditativeness, his improvisational grace. She has, too, his comfort with slipperiness, both in terms of subjectivity—is Guibert the “I” of his novels?—and of form. She is annoyed by the label autofiction, which has dogged her own novels and those of Guibert, but she finds in its manufactured ambiguity a space of freedom, a way to rant and riff on the page while maintaining plausible deniability. And so in this book we get reports of her “sad, rashy breast,” her diarrhea, her hemorrhoids, her shoddy health insurance, her tenuous employment, and the rejection of her latest novel, which occasions a brief defense of imperfect novels rather than “all of the polished turds being published now.”

With this salvo, Zambreno casts herself as an “irritant,” a role she claims on behalf of Guibert as well. She ditches the idea of writing an orderly study of his work in favor of something more protean that openly courts failure: the failure to finish the book. She confesses that she’s been trying to write it for the past three years; pregnancy introduces a new “deadline of [the] body” to write against. Here’s yet another affinity with Guibert, who raced against the deadline—apt word—of his own death. (“Writing is also a way of giving rhythm to time and a way to pass it,” he notes in his hospital diary.) Despite its elliptical style, Zambreno’s book cultivates patience, a digressive but ruminative mode that goes beyond close reading of Guibert toward an actual embodiment of his voice. She imposes slowness and stillness onto his work, which, as she writes, has a naturally “rushed, passionate, desperate, furious character.” Her own maladies provide textual signposts: “It is now New Year’s Day. I am sitting upright, forcing myself to write this scrap, after a sleepless night . . . The past two days I’ve been too sick and exhausted to work on this study . . . The winter of 2020, once my classes begin, I cannot work anymore on the Guibert study.” This culminates in the COVID pandemic, a collective immersion in quarantine, stigma, and contagion that collapses the artificial barriers between book and reader, writer and critic.

Zambreno conceives literature as inseparable from identity but not constrained by it. Her approach demonstrates one version of what reading is for, what literature is for—not to make us more empathetic, much less improve us, but to offer an intellectual, emotional, or creative experience we would not otherwise have. Literature makes life more bearable. And for those who are ill or dying, literature has the additional capacity to make them “more fully human,” as Zambreno suggests. To document our own deaths is to prove that, for a while anyway, we survived.

Still, in the existential hierarchy, the body trumps literature, and you finish Zambreno’s book with the wish that, for all of its seductions, it didn’t have to exist, that there was no reason for it. “He should have been alive now,” Zambreno writes of Guibert, who would be sixty-five today. “He should have lived longer.”

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.