Lina Attalah

Lina Attalah

Reckoning with occupation in an online film series.

Rosalind Nashashibi, Electrical Gaza, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Another Screen.

“For a Free Palestine: Films by Palestinian Women,” programmed by Daniella Shreir, available on another-screen.com through June 18, 2021; filmmakers speak in an online event June 7, 2021

• • •

How does one make a film from within the advancing rot of occupation and its ceaseless, collective catastrophe? How can such a hegemonic background be dealt with—what possibilities might move in the spectrum between the fixed poles of utter denial and direct resistance? “For a Free Palestine,” an online program of works by Palestinian women assembled by Daniella Shreir for Another Screen (the programming arm of the feminist journal Another Gaze), is an attempt at some answers. Those answers variously flicker through these works from disparate times, localities, and sensibilities.

The program is free to view, but it is also a fundraising drive for grassroots efforts in Gaza, following Israel’s recent assault there, and elsewhere in occupied Palestine—one quickly organized during the weeks that protests spread against the planned forced eviction of Palestinians from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in East Jerusalem. Just as, in the news, we saw images of protests by diverse assemblages of Palestinians across the territory, from the naturalized 1948 lands and its mixed cities, to the formerly occupied East Jerusalem, to the falsely “autonomous” West Bank, so too does “For a Free Palestine” give insight into the heterogenous configurations and textures of occupation. And, beyond the specifics of its context, the program can also be seen as a tribute to film’s capacity to reflect, and intervene into, the thickness of the present.

Layaly Badr, The Road to Palestine, 1985. Courtesy the artist and Another Screen.

A starting point of sorts is Layaly Badr’s The Road to Palestine (1985), a pedagogic animated short for children. Its straightforward interpretation of a young girl’s account of witnessing an aerial bombing is in line with how the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and its active film unit were invested in presenting a relatively fixed, linear, undisputed Palestinian narrative to the world. But then come the post-PLO, post–Oslo Accords cinematic experiments: autonomous, reflective, slippery. Most of these later films unfold in contrasting terrains and independently of institutional propaganda. Throughout, that hegemonic backdrop of occupation is never absent, yet certain choices (both formal and in terms of content) might render it unfamiliar, even surprising. For one, film itself is interpreted as a medium that interferes in the very narrative it delivers. For another, while auteur theory is commonly held as canon in experimental cinema of the so-called Arab world, here the self doesn’t emerge through an indulgent “I”—subjectivity unspools instead through minute fragments, undoing any cohesive grand narrative of the struggle.

Razan AlSalah, Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, And So Was the Nakba, 2017. Courtesy the artist and Another Screen.

Two films by Razan AlSalah are particularly attentive to the materiality of disappearance. In both Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, And So Was the Nakba (2017) and Canada Park (2020), the artist uses Google Street View to navigate Haifa and Jerusalem, respectively, in search of sites that have been permanently altered by the occupying forces, but which linger in memory and myth. The tool provides some illusion of access to these sites even while its virtuality indexes their impossibility.

Basma Alsharif, We Began by Measuring Distance, 2009. Courtesy the artist and Another Screen.

Impossibility, a persistent trope concerning Palestine, is also reckoned with in the multilayered practice of Basma Alsharif, a filmmaker raised in France, the US, and the Gaza Strip. In We Began by Measuring Distance (2009), sequences of paced images from the filmmaker’s archive, documentary footage, and staged scenes are poetically edited to different soundtracks, including music from Egyptian star Abdel Halim Hafez’s last performed song, the 1976 classic “The Fortune Teller,” and a narrator telling us about the various forms of measurement that have been undertaken by a certain undefined “we.” The types of counting he describes invoke yet other countings, like how, guided by well-being apps, you might count your breaths in a forceful effort to be mindful. Or how, while daydreaming, the migrant counts the inexact miles and hours it would take to cross the unmeasurable waters to another shore. And in empty time, measuring confronts boredom, whether it is the measurement of everyday objects and shapes, or the measurements between the places and times that construct history. While motivated by vastly different urgencies, these measurements are all functionally meaningless, pointing to the ultimate absurdity embedded in the realm of supposed exactitude—of narrative, of facticity, of reality.

Basma Alsharif, Home Movies Gaza, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Another Screen.

There is an absurdity, too, in Home Movies Gaza (2013), where Alsharif penetrates the domesticity of the Gaza Strip with intimate imagery of everyday life set to the lingering sound of a low-altitude aircraft or drone, marking how “normalcy” is unattainable in a space that is so highly surveilled. That it is one of the most surveilled places on earth makes it almost paradoxical that, as Alsharif grapples with, Gaza also defies representation. Enclaved, the Strip is largely cut off from the world, and the scant representations of it that circulate are of a uniform sameness in their miseries—Gaza’s repetitive destruction has overwhelmed any ability to see it in itself. But training her camera on the quotidian, Alsharif sees Gaza as more than a metonym—as a living place, as a home.

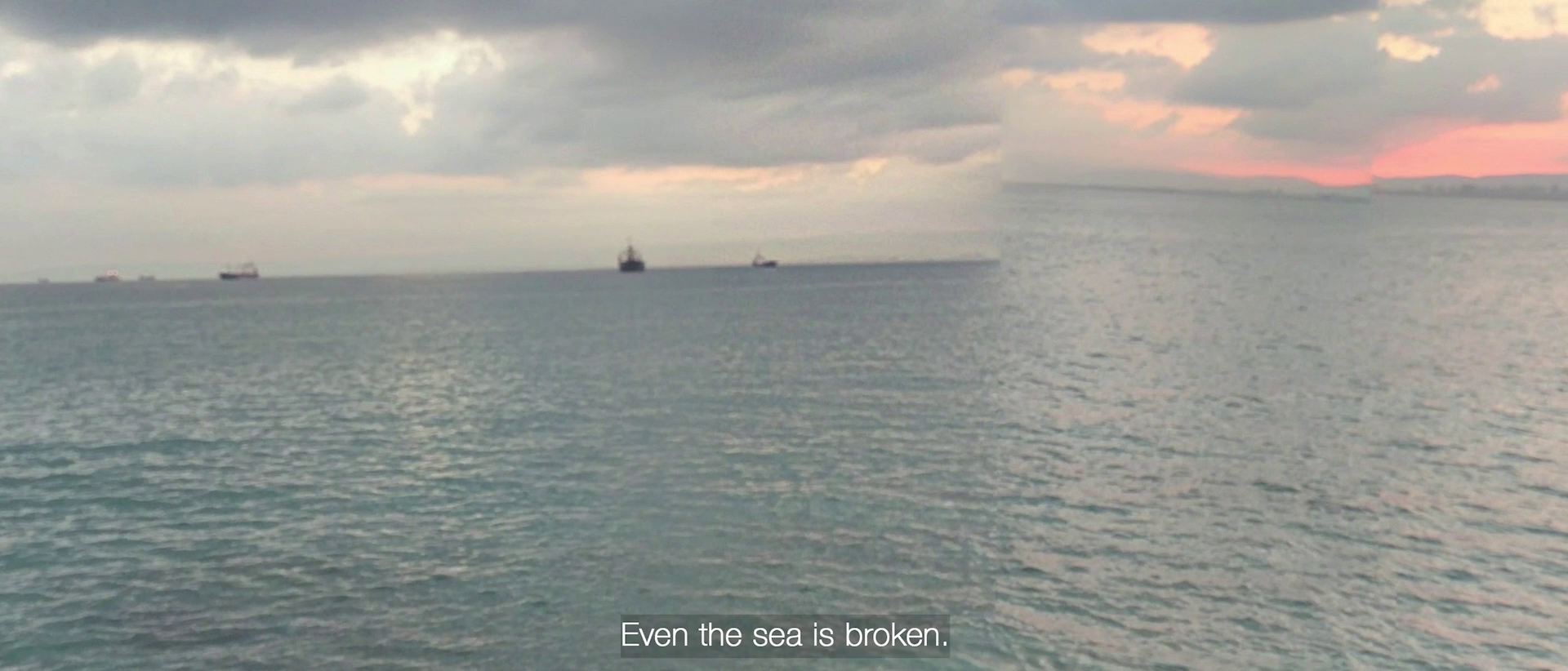

Rosalind Nashashibi, Electrical Gaza, 2015. Courtesy the artist and Another Screen.

Picking up this problem of eclipsed vision is filmmaker Rosalind Nashashibi, who takes to the speculative in Electrical Gaza (2015). This work, too, delivers images of domesticity, here interspersed with animation, as well as an originally composed, upbeat score and the opening fanfare of Les Illuminations, Benjamin Britten’s opera interpretation of a suite of Arthur Rimbaud’s poems. Nashashibi overlays different and new possibilities, imaginaries, and histories onto the body of the real. Her zooming into the Strip, through long and recurrent shots and through unraveling connections using sequence editing, pictures the war-stricken territory with a fresh curiosity.

Jumana Manna, A Sketch of Manners, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Another Screen.

Artist Jumana Manna’s short films zoom in, too—onto shards of subjects that she makes seem as monumental as the sculpture practice for which she is also known. These pieces stand out in the program for the particularly harmonious way they both put the medium of film itself on exhibit and conceive of subjectivity through fragments; there is a fascinating porosity between form and content. From male thug culture manifesting in different sites in East Jerusalem in Blessed Blessed Oblivion (2010), to a 1920s photograph of a Palestinian urbanite upper-class masquerade party in A Sketch of Manners (2013), Manna fearlessly traffics in fragmented particulars, inviting us to see these fractions not as contingent on a broader narrative, but rather as whole unto themselves.

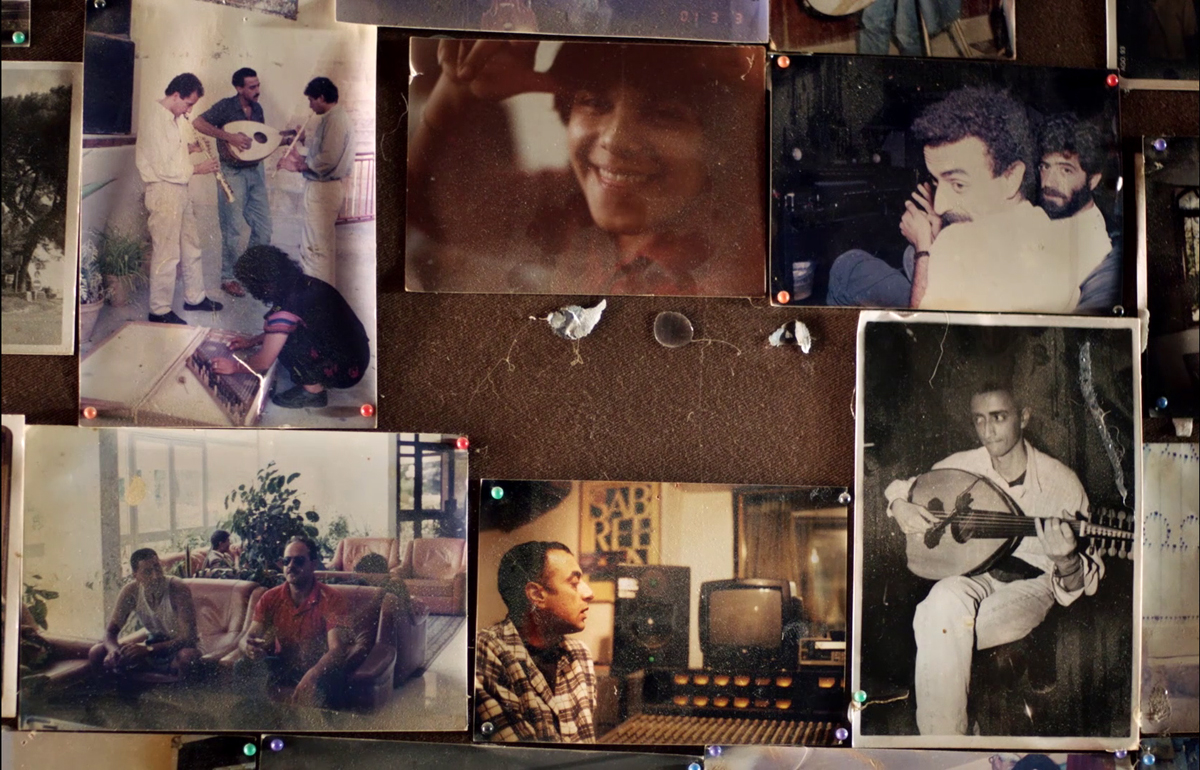

Jumana Manna, A Magical Substance Flows Into Me, 2015.

In A Magical Substance Flows Into Me (2015), Manna crafts an entire and formidable ethnographic document of Palestine by re-creating the journey of a Jewish-German ethnomusicologist who hosted a radio program in the 1930s for the Palestine Broadcasting Service, for which he invited musicians of different descents to perform their vernacular music. We hear various Arabics and Hebrews spoken; we hear tunes and lyrics belonging to places that are totally other from the flat and binary Palestine of the contemporary imagination. The film revels in the promiscuous makeup of this other Palestine, experienced here as a sonic map. Manna’s portrayal of Kurdish and Yemenite Jews, Coptic Christians and Arab Bedouins, and others doesn’t simply and mournfully point to an Edenic social cohesion now lost to politics, but rather, and essentially, to the absurdity of nationalizing the chaotic substance of identity.

These works, like most of the films Shreir has assembled, produce their effects from within the tangled ambiguity that lies between denial and resistance. Their experimentations with form as well as with fictional, speculative, and hyperreal narratives wittingly negotiate their status as art objects within and despite the imperious context of occupation—an overdetermining context that can limit the possibilities of filmmaking to the thin acts of soberly documenting or sentimentally mobilizing. Instead, “For a Free Palestine” is a meaningful index to the sinuous ways that art can tamper with the binds (of power, of politics, of history) that invisibly hinder our perception.

Lina Attalah is a Cairo-based writer and editor. She is the chief editor of Mada Masr, an Egyptian media site.