Megan Milks

Megan Milks

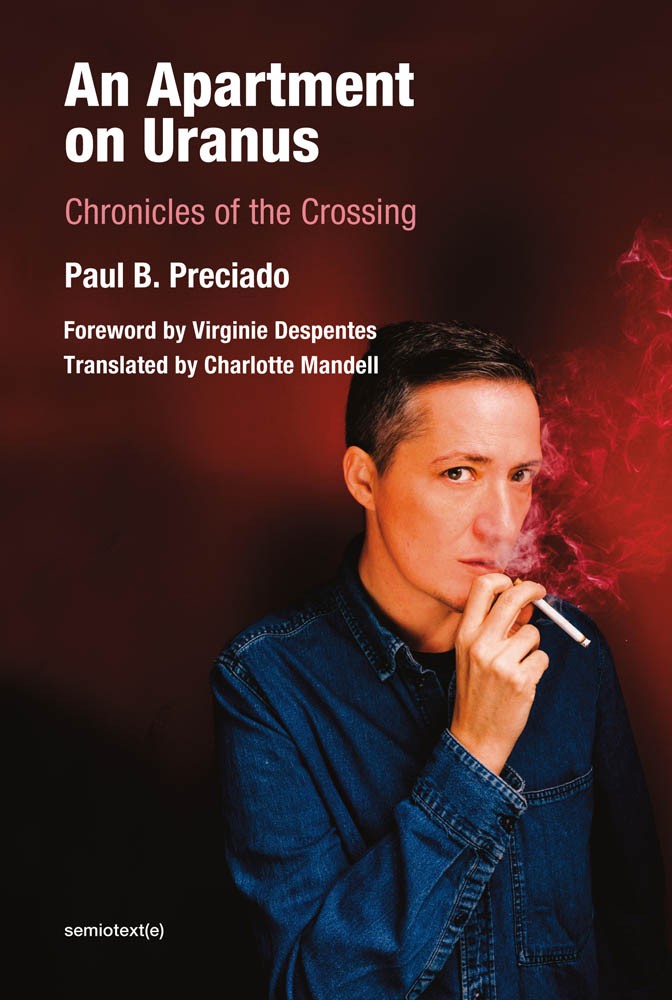

Essayist Paul B. Preciado explores gender and sexual politics.

An Apartment on Uranus: Chronicles of the Crossing, by Paul B. Preciado, translated by Charlotte Mandell, Semiotext(e), 263 pages, $16.95

• • •

“I bring you a piece of horizon,” Paul B. Preciado writes in his new book, a collection of essays titled An Apartment on Uranus. “I come with news of Uranus.” You’d be forgiven for assuming an off-color joke everywhere Preciado invokes that planet’s often punned-upon name—we are talking about someone who decorated his first book with dildo illustrations. The new collection’s provenance is French, and while I suspect Preciado, who also writes in English and Spanish, is neither unaware nor unwelcoming of the English title’s humor, he doesn’t call attention to it, instead explaining rather straightforwardly the title’s invocation of both the far-flung planet and Karl Heinrich Ulrichs’s nineteenth-century theory of androgyny. Preciado revives Ulrichs’s figure of the Uranian, a “third sex” between genders, through his present trans embodiment. “I am the multiplicity of the cosmos trapped in a binary political and epistemological system, shouting in front of you,” he writes. “I am a Uranian confined inside the limits of techno-scientific capitalism.”

An important philosopher-theorist of gender and sexual politics for more than two decades now, Preciado is also an electrifying writer: capable of packaging damning analysis, utopian vision, and flamboyant drama into one fell swoop. He also has quite a range, roving between rhetorical modes with the same itinerant impulse with which he—Spanish-born, holding graduate degrees from two US institutions, and now based in Paris—lives his life. His first book to appear in English, Testo Junkie (2013; published in both Spanish and French in 2008), was critical trans autotheory: a biopolitical analysis of the sex-gender system anchored in the self and his experiments with testosterone. Countersexual Manifesto, published in France in 2000 but much later (2018) in the United States, sketched an absurdist (yet persuasive) totalizing theory of the dildo. More conventionally academic is Pornotopia (2014; first published in Spanish in 2010), a transdisciplinary history of sexual sites (including bachelor pads and rotating beds) through a study of Playboy magazine. Like contemporary luminaries Sara Ahmed and Lauren Berlant, Fred Moten and Maggie Nelson, Preciado is a capacious thinker with an agile and adaptable pen.

In An Apartment on Uranus, Preciado mobilizes that pen in something close to real time, responding to life and events as they play. The book collects more than sixty charismatic essays, mostly columns written for the French progressive paper Libération between 2013 and early 2018 (his column, “Interzone,” is ongoing). In each compact piece, he mixes lyricism and polemic, personal narrative and a transfeminist biopolitical analysis to subjects as disparate as marriage equality, the migrant crisis, human-canine love, Catalan independence, birthdays, breakups, even Candy Crush. These are hot takes, Preciado style. That they each, almost without exception, achieve considerable grace and power may excuse some of the sloppier comparisons they deploy.

And, indeed, analogy is Preciado’s chief analytical strategy here, one of two ways he thinks about crossings. The other has to do with transition. An Apartment on Uranus chronicles a period in which Preciado lived an especially peripatetic life, roaming between multiple homes, cities, nations, and languages while trying to change his legal sex and name. After declining for years to interface with medical institutions that would require a (pathologizing, in Preciado’s view, and inaccurate) diagnosis of gender dysphoria to support transition, he capitulated when the discordance between his identity documents and appearance began to present problems. “With no way out,” he explains, “I agreed to identify myself as a transsexual, as a ‘mentally ill person,’ so that the medico-legal system would acknowledge me as a living human body.” The process in Spain required him to destroy his original birth certificate before he could be approved for a new one, leaving him in a state of semi-undocumented limbo until the new birth certificate arrived. The experience, which filled him with horror—“my trans body does not exist and will not exist in the eyes of the law”—motivates in part his comparisons to the legal gray zones occupied by many migrants.

Preciado revisits periodically this analogy between trans and migrant experience, such that it forms a key throughline. By challenging the imposed structures of the sex-gender system and of familial and national belonging, he suggests, both crossings portend “the radical transformation not just of the traveler, but also of the human community that welcomes or rejects the traveler.” He pushes this analytical conceit further, arguing for the political potential in thinking about crossing—transition—on a geopolitical scale. “We are all plunged in a worldwide transition,” he asserts, describing the cultural and political upheaval in western Europe and beyond.

As with some expansive uses of queer, Preciado’s more elastic trans has uneven effects. Preciado’s temerity with analogy is startling—whether productively or outrageously so, it depends. His comparisons between trans and migrant communities frequently illuminate parallel conditions and present new possibilities for solidarity: “The absence of legal recognition or biocultural support denies sovereignty to trans and migrant bodies,” he writes, calling attention to their shared vulnerabilities.

More dubious are self-aggrandizing declarations like: “The [trans] voice that trembles in me is the voice of the border.” Or: “I am an unlikely cross between Freddie Gray and Caitlyn Jenner.” It’s the positing of Preciado’s own trans body/self as a medium for these other crossings that rings suspect (especially given the absence of any discussion of those who are both trans and migrant). In one column he appropriates the name of the Zapatistas’ Subcomandante Marcos, calling himself Marcos as a way “to collectivize my face.” In his introduction he addresses the pushback he received from Latin American activists who felt that, as a white Spaniard, the name wasn’t his to claim. They “were probably right,” he concludes, unruffled.

But Preciado has never been a tentative writer. When not overreaching, his use of the personal is generally both captivating and politically salient. In the no-holds-barred “The Courage to Be Yourself,” an invited talk for a French festival of ideas, he refuses to play nice with the topic he’s been given: “Today you are granting me the privilege of talking about ‘my’ courage to be me,” he begins, adopting direct address performatively to call out hegemonic society, “after making me bear the burden of exclusion and shame throughout my entire childhood.” Rather than agreeably narrating his journey to some pretense of self-liberation, he condemns social complicity in queer/trans oppression. “You are granting me this courage,” he goes on, “the way you’d leave a few casino chips for a gambling addict, all the while continuing to refuse to call me by a masculine name.”

This talk ends on a revolutionary note, a beat that holds steady across these short dispatches. If the sustained urgency threatens to grow fatiguing, it is a testament to his endurance in keeping such sentiments alive in this long and painful transition to—we don’t know yet. Here in the in-between, I trust Preciado to keep that beat, one eye turned to the night sky’s seventh planet while throwing fire at injustice from the ground.

Megan Milks is the winner of the 2019 Lotos Foundation Prize in Fiction and the author of Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, as well as of four chapbooks, most recently Kicking the Baby, an essay in four parts.