Megan Milks

Megan Milks

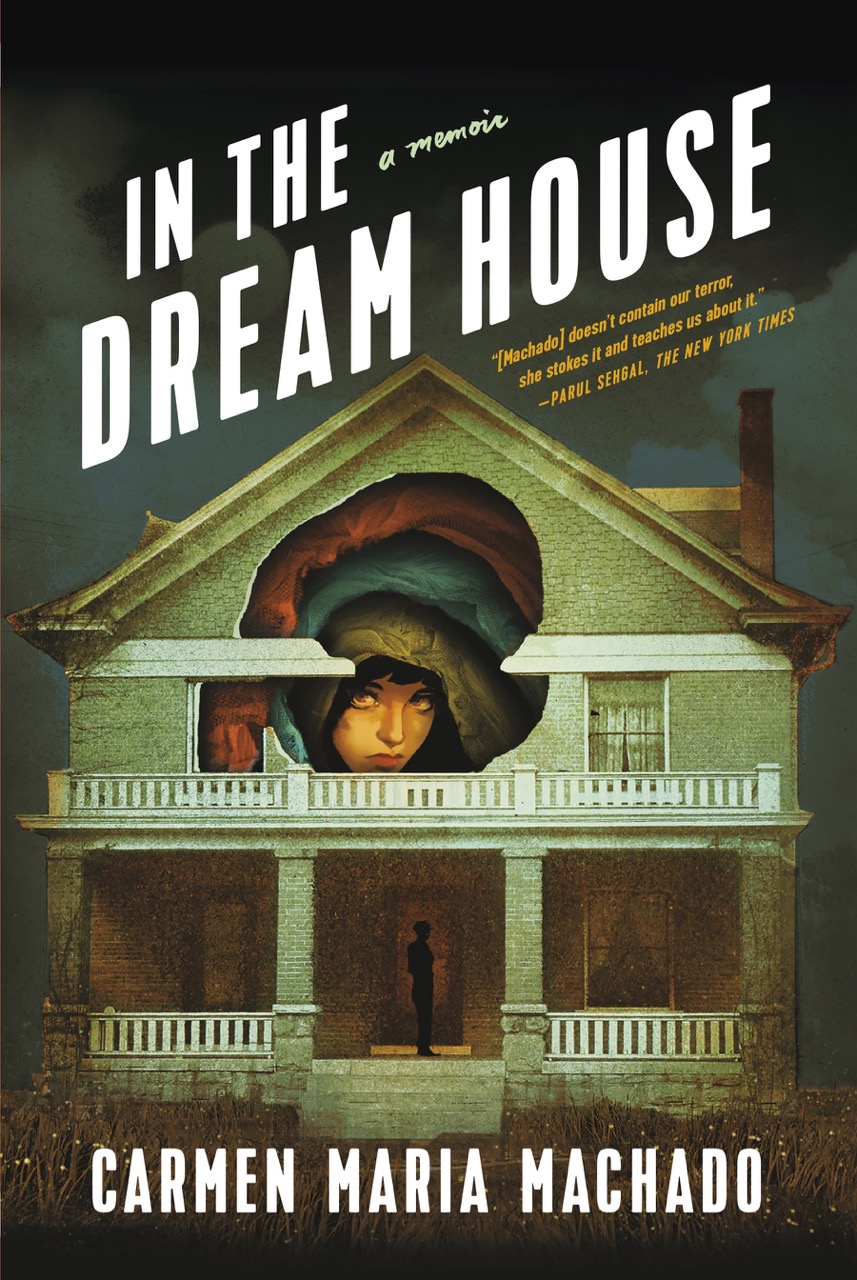

Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir looks at abuse in queer relationships.

In the Dream House: A Memoir, by Carmen Maria Machado,

Graywolf Press, 247 pages, $26

• • •

I remember the weariness with which my friends responded to each new episode I divulged about the abusive relationship that defined my late twenties. Even as I registered their discomfort, the stories burst out of me with a deranged thrill, twisted into what I hoped were riveting entertainments, the worst parts kept to myself. My friends weren’t fooled by these distortions, and neither was I. At night my brain churned through the details of each scene with my girlfriend, each alarming exchange, trying to assert cause and effect, create motivation, anything to solve the mystery of her volatile behavior. I needed to find the right story, the one that would justify everything, or give me meaning, or a lesson, or the end.

I couldn’t. One hallmark of an abusive relationship: you may think you’re in one kind of tale, but it invariably morphs into another. Because it pretends to be a safe space, a dream house; until it is revealed to be dust. The painful bewilderment of this experience both begs for and defies narrative clarity.

In her new book, and first memoir, Carmen Maria Machado blasts her own experience with an abusive intimate partner into a sparking arc of story bits. Cycling through a staggering array of modes and strategies, In the Dream House wheels in and out of fabulist, formalist, and realist registers, cultural analysis and polemic to produce a fresh and unflinching interrogation of abuse in queer relationships. The structure holding it all together is a house: the titular Dream House, its chambers built of the stuff not of dreams so much as story. The Dream House corresponds to her then-girlfriend’s Indiana home, where many of the memoir’s scenes of abuse take place. But the Dream House is also a device, the central design of the book, which is constructed of as many narrative chambers as Machado can conceive.

That is to say, a lot. This is that Carmen Maria Machado, after all, whose widely celebrated debut, the 2017 short-story collection Her Body and Other Parties, delivered a potent blend of surrealism, horror, folk tale, and science fiction within inventive structures. A cataloguing of lovers becomes an account of a virus as it spreads; a sprawling novella emerges out of the episode titles to Law and Order: SVU. Their genre play and formal experiments notwithstanding, works like “Mothers” and “The Husband Stitch” are at heart about gaslighting, boundary violations, a partner prone to rages. In a way, Machado has already been telling us her story.

With In the Dream House, she removes the veil of fiction, even as she outfits her experience in a series of narrative sheaths, some semi-fictive. “Dream House as Erotica” is—what it sounds like. “Dream House as Omen” captures Machado’s first encounter with her girlfriend’s sudden rage. Other sections posit the Dream House as “Romance Novel” (where her girlfriend first blurts out the l-word), as “Unreliable Narrator” (a meditation on credibility in the context of abuse), as “Haunted Mansion” (Machado in the role of ghost). “Sci-Fi Thriller.” “Schrödinger’s Cat.” Shaking off one plotline for another, one trope for the next, the memoir pummels forward with urgency, asking: What happened here? How? Why? Our narrator can no longer rely on reality, after all: the woman in the Dream House made sure of that. To live in the Dream House is to live in a state of narrative confusion, Machado suggests, even as she relies on that structure to organize the chaos.

A new rash of memoirs and autobiographical novels (Kiese Laymon’s Heavy, Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous) are directed at an epistolary “you.” Machado adopts the second person more classically, as a dissociative swerve from the first. “I was cleaved,” she writes, “a neat lop that took first person—that assured, confident woman, the girl detective, the adventurer—away from second, who was always anxious and vibrating like a too-small breed of dog.” As Machado’s “you” pivots inward and outward to implicate the reader to varying degrees, it produces a tension between author and audience.

Machado exploits this double address most directly in “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure.” You wake up. The woman in the Dream House is angry because, she seethes, “you were moving all night.” You, terrible you, kept her awake. How do you react? Three choices lead to different paths, none of them protecting you from escalation. The day is ruined. That night, you engage in distant, disembodied sex, then drop off to sleep and dream. Eventually you are waking up, and she is accusing you, again. Into this closed, recursive system, Machado has snuck a few originless branches addressing the reader openly. “You shouldn’t be on this page,” she chastises us. “You flipped here because you got sick of the cycle. You wanted to get out. You’re smarter than me.” The slight tremor of embarrassment that runs through Machado’s book may be among its most poignant features.

Periodic returns to the first person let us come up for air. In these sections Machado offers the clarity of retrospective analysis while connecting her experience to the broader social problem of queer partner abuse and the silence that cloaks it. “I have spent years struggling to find examples of my own experience in history’s queer women,” Machado writes, her investigations unearthing a frustratingly small body of literature on abuse in lesbian relationships. She packs her archive with representations of abused women more generally—finding them most readily in folk tales (a running sequence of footnotes indexes the many folk motifs that appear in these pages) and psychological horror (her discussion of the film Gaslight is particularly compelling).

Given the limited histories available, Machado’s hyperstoried memoir aims to fill in—even overstuff—this blank. “I speak into the silence,” she writes. “I toss the stone of my story into a vast crevice; measure the emptiness by its small sound.” If her point stands, the image is overmodest. This book’s impact will be more emphatic, considerably, than a plink. In the Dream House arrives with a thunder that resounds.

Megan Milks is the winner of the 2019 Lotos Foundation Prize in Fiction and the author of Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, as well as of four chapbooks, most recently Kicking the Baby, an essay in four parts.