Megan Milks

Megan Milks

Close to her: Karen Tongson revisits the soft-rock icon.

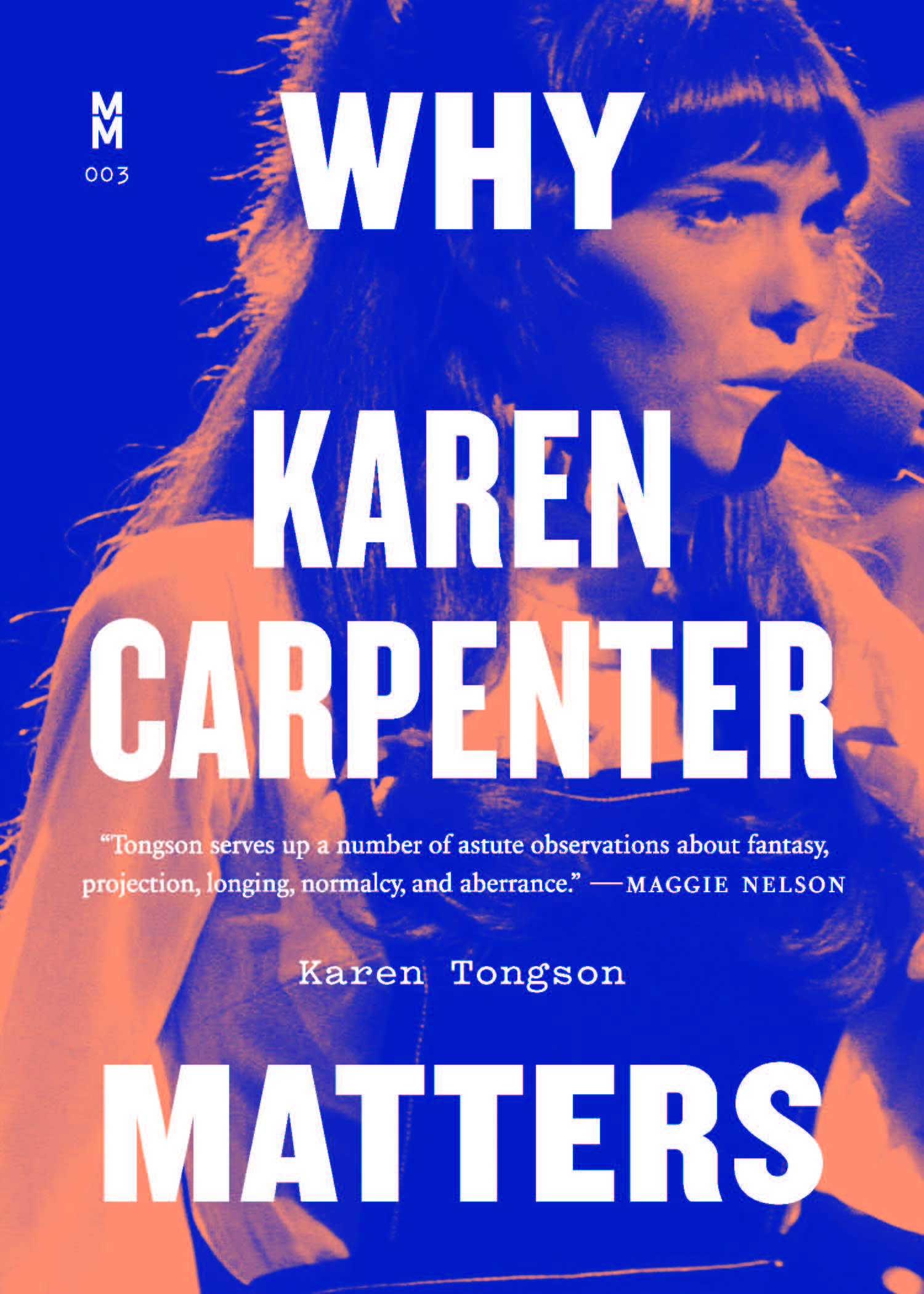

Why Karen Carpenter Matters, by Karen Tongson, University of Texas Press, 138 pages, $16.95

• • •

A remarkable thing happened while I was working on this review. Diving into the Carpenters’ discography, I found myself—almost without knowing it, without agency or control, spontaneously, as if taken over by a benign but powerful force—singing. There’s something about Karen Carpenter’s voice: the crisp enunciation and warm, rounded vowels; the earnestly affected emoting, doubled, tripled, held in harmony; the audible smile and come-with-me nods. I can’t help it, I’m impelled, slipsliding through lyrics I don’t actually know but the songs are so songy, they lead me right through: we’ve only just begun, they entreat, to live. They need me, I think. Karen needs me.

In this way I’m contributing to her resuscitation, or to what Karen Tongson, in her new book Why Karen Carpenter Matters, describes as her “queer afterlives.” Since her tragic death, at age thirty-two, in 1983 from complications related to anorexia, Carpenter has been the subject of three documentaries and a cult film (Todd Haynes’s early, brilliant Superstar), at least two biographies, innumerable newspaper and magazine features. (And these are the Karen-specific artifacts, discounting the vast archive of material on the Carpenters, the band she formed with her brother Richard in 1969.) If the subject of Tongson’s idiosyncratic and very fun book is not that Karen Carpenter matters—a given of the title—but why, it’s also where, how, and above all to whom. Karen has lived on, Tongson argues, through an unlikely diaspora encompassing Filipinos and Filipino Americans, people of color, immigrants, queer and gender-nonconforming people, pretty much “everyone other than the white Nixon-era suburbanites she and her music are said to have represented.”

Tongson’s queer genealogy centers the margins, then, and is oriented around the author herself. “You see,” she explains, “my Filipino musician parents named me after Karen Carpenter in 1973.” Close to a decade later, when she was nine, she learned of Carpenter’s death as Tongson’s family were arranging flights to Southern California, where they would eventually settle not far from Carpenter’s home in Downey. Other parallels emerge, such as between Carpenter’s tomboyish nature and Tongson’s butch, gender-nonconforming one, and between their shared band-geek identity (Tongson played the saxophone; Carpenter, the drums). These flashes of memoir set the stage for wide-ranging cultural analysis.

The third in the University of Texas Press’s new Music Matters series, this engrossing installment follows equally absorbing meditations on the Beach Boys and the Ramones. Edited by music critic Evelyn McDonnell, the series offers informed personal takes where writers and scholars get to be fans even as they commit to rigorous appraisal. An enthusiastic and persuasive Carpenters fan, Tongson is also a stellar critic with extensive knowledge of music and songcraft, here displayed with gusto in enthralling close reads. (Her discussion of “Goodbye to Love,” arguably the first power ballad with its “gooey harmonies” fading out for a fuzz guitar solo, is particularly vibrant.)

While the music writing is superb—jaunty, eloquent, and illuminating—some of the biographical material can drag. Already canonical in American pop, the Carpenters have been discussed at length, and though Tongson does a fine job sifting through that body of criticism, there’s a fusty quality to the band’s history as revisited here. Some of the best moments in this compact book are those filtered through Tongson’s fascinating biographical and affective connections to Karen. I would have loved to spend more scene time with Tongson, who prefers commentary to narrative. Beyond a few selective childhood moments and backstory glimpses, as a character she remains mostly offstage.

In addition to a scholarly monograph on suburbia, Tongson has also published on karaoke (she’s a fanatic, and a pro). Her discussion of mimicry and reproducibility in the Philippines, drawing on this scholarly work, leads to some of Tongson’s most inspired leaps about Karen’s “reanimation.” If in the US the Carpenters became démodé, in the Philippines they became ubiquitous: “I challenge anyone visiting the Philippines, now or then, to try to last a day—nay, several hours—without hearing a Carpenters song on the radio, or in a karaoke establishment, or performed by a cover band.” Why? Tongson points to Filipinos’ deep respect for Richard’s skill with arranging music—a surprising portion of Carpenters songs are magnificent, hit-making covers—and more lax cultural values around authorship (owing, in part, to “a long colonial history in which ‘mimicry’ has been heralded as our greatest skill”).

In 2015 Tongson coined the term “normporn” to describe queer fixation with TV shows that spectacularize normalcy, and the Carpenters may be the musical version. “There’s something totally queer about the Carpenters,” Tongson writes, pointing to not their (presumably straight) sexualities but what seems like their suspiciously hypervigilant, beyond-normal normalcy: international pop star Karen’s insistent desire for a perfect middle-class suburban life, for example, and Richard’s meticulous workmanship, which produced classics of easy listening while making him seem like a robotic creep.

Tongson reports her own similar grasping for “exemplary normalcy.” (It would take some time for her to realize it would be “inherently impossible to achieve, let alone maintain, for someone as brown and queer as me.”) And so it was a bit mind-boggling for young Tongson to learn that her love of the Carpenters, which she hoped would ease her entrance into this new American context, marked her as more, not less, foreign. Revered in her country of origin, the Carpenters were considered “corny” in the US. A word, she observes, that has likewise since fallen out of fashion, retaining “saliency in everyday usage in the Philippines, even though it has long been phased out of the American vernacular.”

Now, of course, the Carpenters’ wincing sincerity makes them wonderfully camp. There’s a similarly campy sheen to Tongson’s prose, which sparkles perhaps a bit too (deliberately) much. Take the economical, alliterative punchiness, for example, of “Karen Carpenter is, at once, my blessing and my burden.” Or this: “Through Karen,” she notes, “I came to understand that soft rock might not signal a weakness or vulnerability, but instead announces a strength.” Elsewhere there’s a “Hedwigian” venue and two band members “yented” together (from “yenta,” or “matchmaker”). I count just one “pun intended,” though get the sense she’s restraining. Tongson’s sentences are admirably compressed, tidy, and polished. If they verge on a little too too (are people saying that anymore?), they are playfully so, bringing an ambiguously ironic gloss to a book that is, in part, about reclaiming or at least troubling “corniness” in a post-ironic age. Flickering between irrepressible sincerity and winking mirth, Tongson’s prose can be, like the Carpenters’ music, both a bit schmaltzy and a triumphant delight.

Megan Milks is the winner of the 2019 Lotos Foundation Prize in Fiction and the author of Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, as well as of four chapbooks, most recently Kicking the Baby, an essay in four parts.