David O’Neill

David O’Neill

“At least the dead don’t bust your balls”: Édouard Louis writes

about his père.

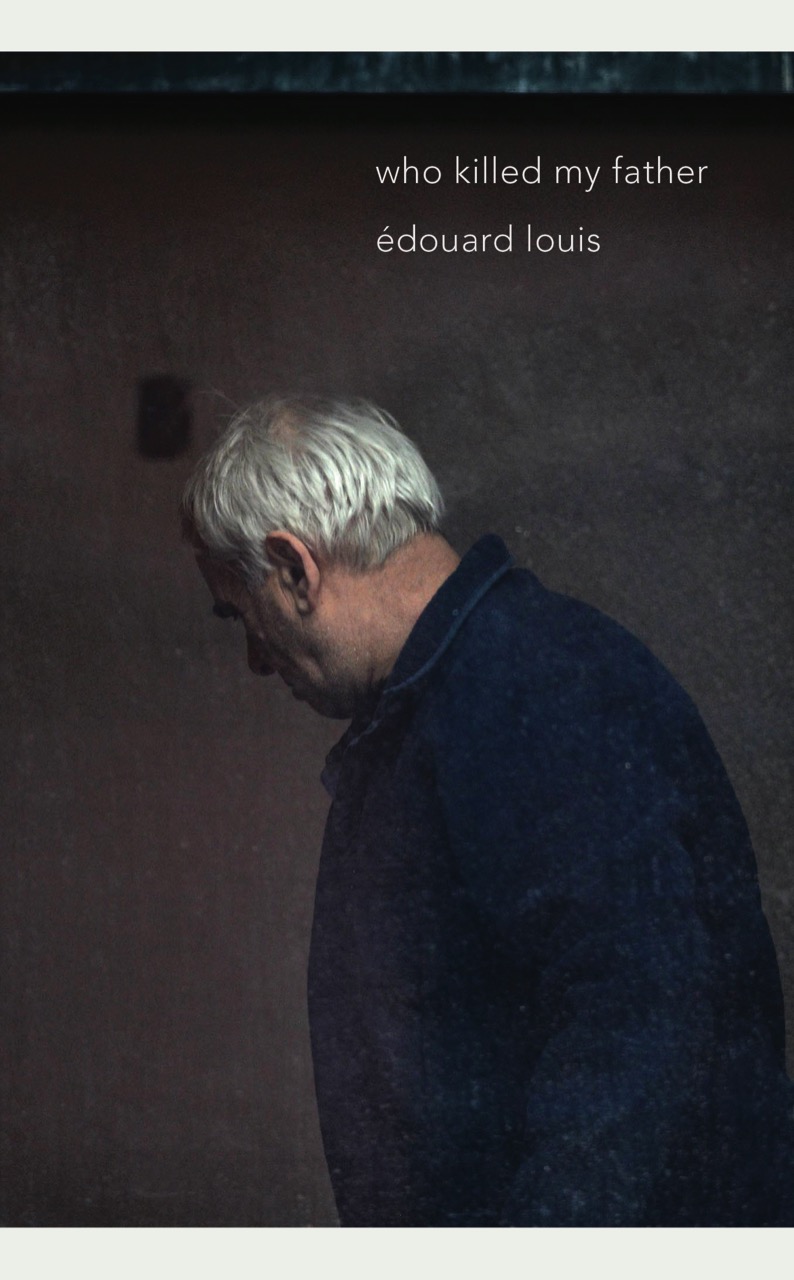

Who Killed My Father, by Édouard Louis, translated by Lorin Stein, New Directions, 87 pages, $18.95

• • •

On a winter’s night in 2001, a French boy, eight or nine years old, dreamed of being a pop diva. He decided to debut at a small family party. He huddled with three friends and schemed: he would be the frontwoman and the others would be the slickly choreographed band, everything would be fabuleux, his father would be proud. But his father wasn’t proud. He was embarrassed. As the boy later wrote, “All the grown-ups were watching except for you. I sang louder. I danced harder to make you notice me, but you weren’t watching. I said, Look, Dad, look. I was putting up a fight, but you weren’t looking.”

Two decades later, the boy, Édouard Louis, has everyone looking. His roman à clef, The End of Eddy, was published in 2014, when he was twenty-one; since then, he’s become an archetype of the bourgeois literary culture he both disdains and lives for, the working-class wunderkind who articulates ugly truths beautifully. He writes stylishly and unsparingly about the violence he suffered growing up poor and queer, his sexual assault, his father’s everyday sadism (even kittens are not spared), his home village’s ferocious social maladies. His new book, Who Killed My Father, is a short, wrenching, tender-hearted essay addressed to his dad. (Despite the book’s title and elegiac air, Louis’s father is still alive, though barely. He’s just fifty years old, but seems much older, battered and sick after a lifetime working in a factory and sweeping streets.) Who Killed My Father picks up ideas from both The End of Eddy and Louis’s second novel, History of Violence (2016): how societal injustice plays out at ground level, how poverty twists minds and bodies, how the oppressive codes of masculinity hurt everyone, not least the men who most zealously uphold them.

In Who Killed My Father, Louis is not dancing as hard. The book is lean and understated. The paragraphs, some no more than a couple lines, are set as self-contained fragments, each a bright memory or insight flashing before the next jump cut. Louis narrates small moments from his father’s life, told as if Louis were watching from miles away: his dad giving him a watch that runs backward or saying during an eclipse, “The next time something like this happens on Earth we’ll all be dead”; eating “fistfuls of grated cheese” with his “mouth over the wide-open bag”; saying he’d like to work in a morgue because “at least the dead don’t bust your balls.” Louis’s father grudgingly buys his son a copy of Titanic, even though it’s “a movie for girls.” A small gesture, yes, but quite an evolution for a man who, in the End of Eddy, drank warm blood from a freshly butchered pig. The book often lingers on descriptions of the father’s body. His belly has “so badly overstretched that it has ruptured,” his back is “mangled, crushed,” and his heart “can’t beat without assistance, without the help of a machine. It doesn’t want to.” This attention to the corporeal is key. As Louis writes to his dad, “The history of your body stands as an accusation against political history.”

In other words, Louis portrays overarching political forces in the flesh: neoliberalism, he implies, is the way in which his father gets winded just walking to the bathroom and back, apologizing for his weakness the whole time. While The End of Eddy offered sociological master shots, mini-essays that explained, professorially, why everyone was suffering, the new book does that less, mostly letting the facts say what they will. Still, Louis frames his (always unnamed) father as emblematic, tracing his perpetual humiliation, under which he suffered in turn, back to the cruelty of the state toward the poor, the way they are scapegoated and then forgotten, struggling under policies that are de facto death sentences. Louis can offer this generous reading in part because he’s the one holding the pen—nothing readjusts a familial power imbalance like world fame—but his ambivalence about his father still shows sometimes. One sentence, isolated by conspicuous white space, reads: “It often seems to me that I love you.” Louis would never use nine words to say what only takes three. The first six are a hedge he might still need.

He’s less hesitant to name the villains of the book: former French president François Hollande and the former labor minister Myriam El Khomri, former prime minister Manuel Valls and president Emmanuel Macron. Because these politicians crafted heartless welfare laws couched in disingenuous language about fairness and opportunity, Louis hates them more than any boy who spat in his face for being queer, or any villager, who, like his father, voted for the demonically far-right Le Pen dynasty. To answer the unpunctuated query in the book’s title, Louis pins the Macrons of the world against literature’s spreading board, classifying them as the worst of the worst: “I want these names to become as indelible as those of Adolphe Thiers, of Shakespeare’s Richard III, of Jack the Ripper. I want to inscribe their names in history, as revenge.” What really enrages Louis is that the ruling class, and those who empower them, don’t even really care about politics. For the poor, it’s “life or death”; for everyone else, it’s “a question of aesthetics: a way of seeing themselves.”

Predictably, the class that wrecked Louis’s father has co-opted the son, at least in North America. These days, Louis talks working-class revolution while looking cool on e-commerce fashion sites and has become the go-to guy for glossy articles about the French proletariat. In December, the New Yorker rang to glean his thoughts on the gilet jaunes (yellow vests) protest movement; he said the surprising thing was that there wasn’t more vandalism. For a long time, I would’ve thought being a legacy-magazine revolutionary was viciously self-defeating. Now, I’ll take it.

In families, as in politics, the question is always: Who is getting revenge on whom? Especially with fathers and sons, the answer is never clear. Like many remembrances of a parent, Who Killed My Father is structured as a mystery story without a plot. The son sees clues everywhere, but they don’t solve anything. One detail, though, seems significant as Louis endeavors to answer the book’s main riddle: Why, really, was his father upset by that boyhood performance? Louis’s dad despises femininity in men, and yet Louis finds a photograph of him dressed as a cheerleader. Something in the photo surprises him more than the wig or lipstick or skirt. His father is smiling.

David O’Neill is a writer in New York, an editor of Bookforum, and the coeditor of Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz, published by Semiotext(e).