Daniel Penny

Daniel Penny

Pinking and winking: the Met peruses a once-subversive style.

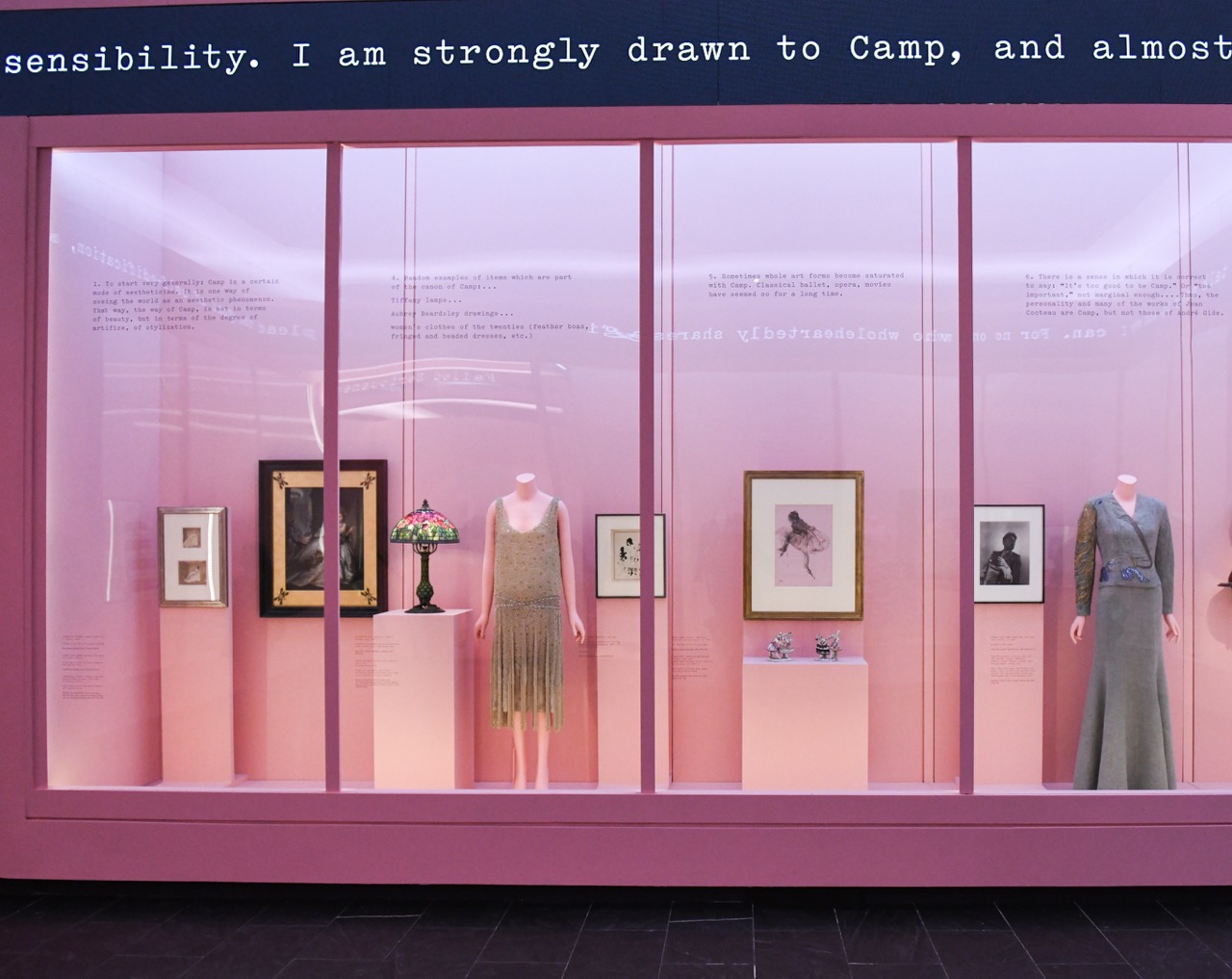

Camp: Notes on Fashion, installation view, title gallery. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com / Zach Hilty.

Camp: Notes on Fashion, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through September 8, 2019

• • •

To take up the topic of “camp” is to enter a melee of discourse. Is camp a set of exaggerated gestures and decorative flourishes, a secret language, or a critical sensibility? What’s the difference between high camp and low camp, naive and intentional? Is camp an affront to good taste, a topsy-turvy product of affluence, or an enduring aesthetic category? Now that it has left the cultural margins and entered the mainstream—as evidenced by its reverent treatment at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—is camp even relevant anymore?

Oscar Wilde, Christopher Isherwood, Mark Booth, and, of course, Susan Sontag loom over the exhibit Camp: Notes on Fashion, each pushing their own answers to these questions and trying to establish a canon. Likewise, a veritable chorus line of designers past and present vie for camp supremacy, among them: Elsa Schiaparelli, Jeremy Scott, Karl Lagerfeld, Jean Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Demna Gvasalia, and Alessandro Michele (the flamboyantly layered creative director of Gucci, which is also the show’s sponsor). Curator Andrew Bolton has attempted to bring together these unruly camp personalities into a single space. At the same time, he tries to assert a history of the slippery concept in the exhibit’s “whispering gallery,” stringing together London mollies, French courtiers, and the beau ideal (and occasionally veering into didactic esotericism). Ultimately, we arrive in a cacophonous, lavishly costumed present, which positions camp as both enigmatic and universal. With a shrug and a wink, the exhibit seems to say that under the right circumstances, anything can be camp.

Camp: Notes on Fashion, installation view, “Camp Beau Ideal” gallery. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com / Zach Hilty.

The entrance of Camp: Notes on Fashion announces a rigid color scheme: pink! The exhibit walls, the catalog, the postcards in the giftshop, are all pink, but not in a campy way. They’re more of a millennial pink, the color of frosé or the living room decor of a minor Instagram influencer. Perhaps curator Bolton hasn’t realized that the queer qualities of pink have leached out of the color—a kind of metonym for the conceptual issues of the whole exhibit. Like the rosy hue of the museum’s walls, which now only suggest a tasteful hipness, camp, at least as presented here, has lost its subversive edge.

The exhibit may falter with its Pepto color scheme, but Camp: Notes on Fashion makes excellent use of the Met’s rich collection of clothes, while also drawing on a bevy of paintings, illustrations, furniture, music, and video. Highlights include Paul Cadmus’s masterfully raunchy painting The Fleet’s In! (1934) and a fascinating eighteenth-century engraving of a fencing demonstration between a man and woman known as the Chevalier D’Eon—a French spy banished from court, who lived the second half of her life as a lady. The Chevalier, wearing a black dress, lunges forward, touching the tip of her sword to her opponent’s chest. The presence of the print is meant to illustrate camp’s enduring interest in gender bending, but it succeeds more on charm than explanatory power.

Other pairings feel tediously literal: portraits of Wilde alongside homages to his outfits. While you admire Wilde’s visage, speakers pipe in Rupert Everett (who played Wilde in a recent biopic) reading the first dictionary definition of camp from Passing English of the Victorian Era. Everett’s murmurations are interspersed with Judy Garland singing “Over the Rainbow.” A similar, interdisciplinary approach to fashion curation has animated several of the Met’s recent shows, such as China: Through the Looking Glass and Heavenly Bodies, with varying degrees of success. Here, the visual culture contextualizes the excessive design language of the clothes, but sometimes overwhelms them. This claustrophobia is aggravated by Jan Versweyveld’s arrangement of the exhibit space, which is deliberately cramped in the first half.

Camp: Notes on Fashion, installation view, “Sontagian Camp” gallery. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com / Zach Hilty.

Thankfully, from these narrow quarters we emerge into what the museum describes as a “Sontagian” antechamber filled with items enumerated in her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp”: a Tiffany lamp, an Aubrey Beardsley illustration, and a pair of dresses exploding with feathers and ruffles. Installed above the glass displays is an electronic ticker tape that slowly fills with Sontag’s thoughts, complete with the sounds of a banging typewriter. Bolton described this touch in his press preview remarks as “like a Jenny Holzer.” Though it is in bad taste, it is not camp.

Camp: Notes on Fashion, installation view, “Part 2” gallery. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com / Zach Hilty.

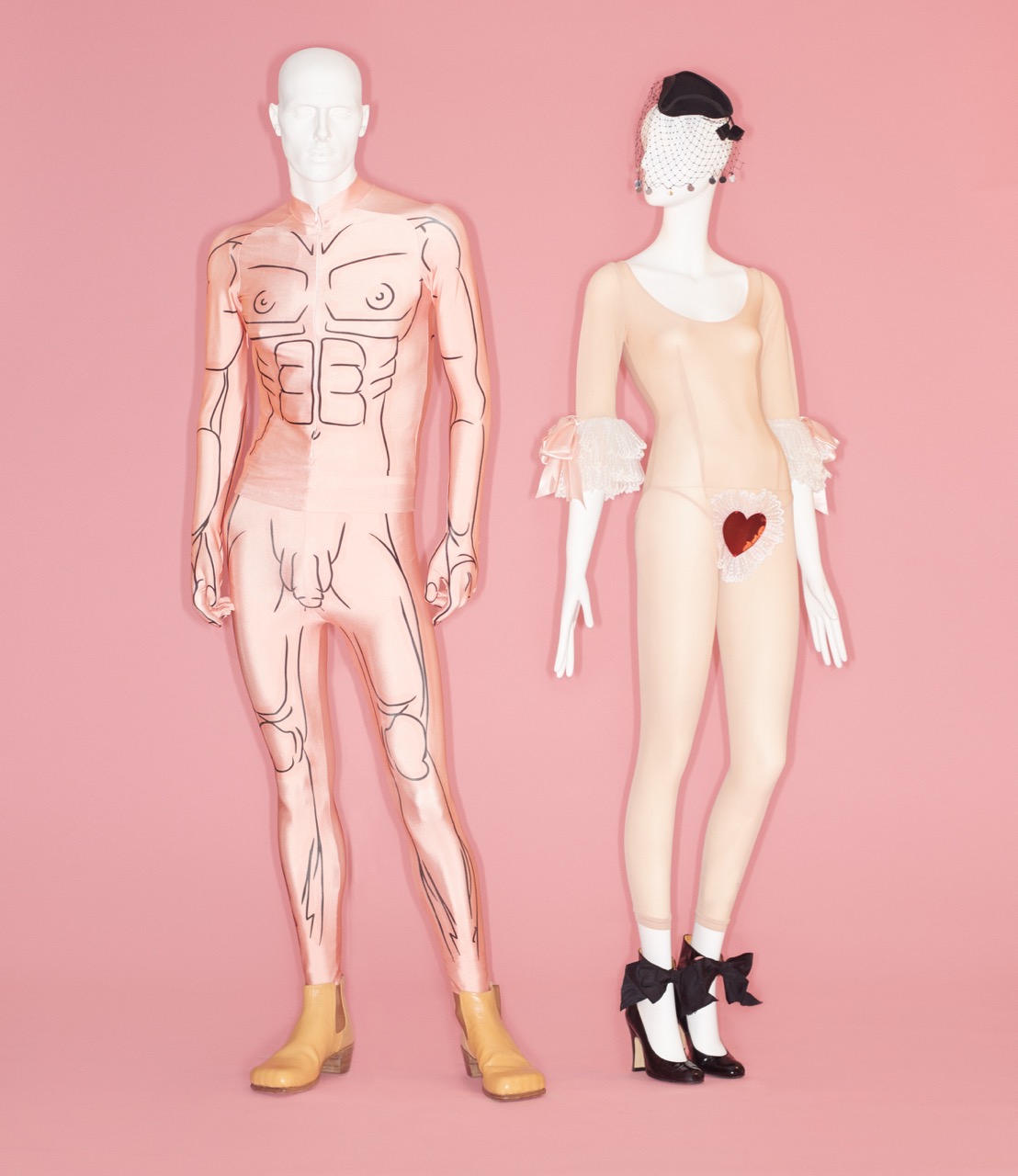

In the final section, the costumes beat out theory. Here, two levels of outrageous designs line the space, with a rectangular display of accessories anchoring the center. Divided into themes like “Cultural Slumming” and “Gender with Genitals,” the space suggests a kind of kaleidoscope of camp, dominated by trompe l’oeil, saturated colors, garish and mismatched patterns, and a copious amount of organza, ruffles, sequins, and feathers. The bonkers “he-man” designs of Walter Van Beirendonck, such as a faux-muscled body suit with girthy dick, or a neon-green life vest with inflatable tube nipples, reminded me how underrated the Antwerp provocateur is—while the massive TV-dinner kimono (designed by Jeremy Scott for Moschino) appears deliciously appalling.

Left: Walter Van Beirendonck, spring/summer 2009. Right: Vivienne Westwood, fall/winter 1989–90. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: © Johnny Dufort, 2019.

Notably absent from this roster, however, are many well-known artists and designers of color. A single piece by Dapper Dan (the Gucci knockoff king) appears in the show, and vogueing master Willi Ninja gets a brief nod in a video installation—but there are no designs by Telfar or Hood By Air, and not a single piece worn by RuPaul, who is perhaps camp’s most visible contemporary emissary. At the gala for the exhibit, Lena Waithe wore a jacket emblazoned with the phrase: “Black Drag Queens Inventend Camp” (the spelling Waithe’s). While this declaration isn’t really accurate, it raises a fair point about how glaringly white Camp: Notes on Fashion is, both in the history it constructs and in the selection of designers it puts forward.

And though the curators have supplemented camp fashion with almost every kind of kindred art and design, they seem strangely oblivious to contemporary camp’s primary habitat: social media. Where are the Kardashian reaction GIFs or Real Housewives memes, whose ludicrous expressions have come to dominate our mediated exchanges? Critics and practitioners of camp often have a historical bent; like Walter Benjamin’s reading of Paul Klee’s drawing Angelus Novus, camp is thought to face backward, glomming onto whatever was once tacky and out of date. But as the cycles of aesthetic production and consumption whirl ever faster, it behooves us all to consider what chunks of our everyday lives are already being repurposed to campy effect.

Daniel Penny writes about art and culture at the New Yorker, the Paris Review, Boston Review, frieze, and elsewhere. He teaches writing and visual culture at Parsons School of Design.