Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

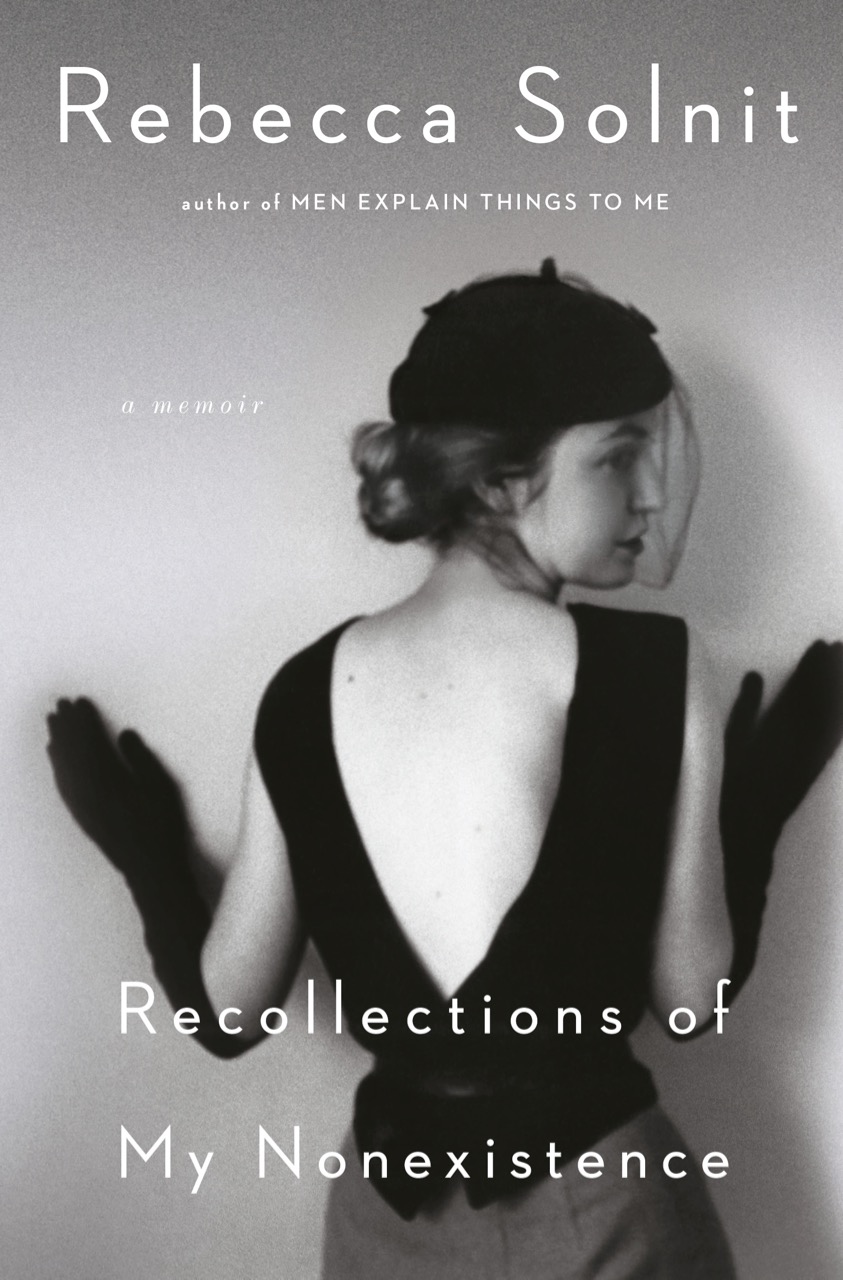

Punk and art, survival and erasure: a new memoir from Rebecca Solnit.

Recollections of My Nonexistence, by Rebecca Solnit, Viking,

244 pages, $26

• • •

Can you write an autobiography and leave yourself out? Can you be everywhere and nowhere in a narrative, or slip out of it like you would quietly exit a party? Provocatively, Rebecca Solnit has organized her new memoir around moments when she felt that she was not fully present in her own life: was not being seen or heard, or was trying to vanish. Writing itself is beset with conflicting impulses to appear and evade, to efface yourself and to insist on your own existence, “to be safe and to be someone.”

In her 2013 memoir The Faraway Nearby, the essayist and cultural historian wrote of taking possession of her own story, her choice “to tell stories rather than be told by them.” In Recollections of My Nonexistence she again looks back, but in a more polemical mode, making arguments about narration, agency, and the risks of silence. Gloriously digressive when she’s not working her ideological seam, she sweeps from specific phenomena—the obsolescence of the pay phone, the indescribability of a sunset—to philosophical meditations, as she considers the body and its limits, power and powerlessness. What Solnit wants most to talk about are the obstacles her younger self found in search of an authority she could hardly imagine. She’s concerned with the way young women disappear, or are encouraged to abdicate their bodies and their vocation.

Solnit arrives in the book as a provincial bohemian, an ’80s punk kid escaping a dysfunctional family and a Bay Area suburb. Her refuge was pre-gentrification San Francisco, a city that had enough of a scene to make you feel alive, where you could do the necessary work of self-creation. And where you could still get an apartment: her Bildung begins with the studio in San Francisco’s Western Addition that she found at nineteen, in 1980, and lived in for a quarter century.

“I didn’t make a home there; it made me,” she writes, devoting some of her most lyrical prose to the apartment, which becomes both a piece of real-estate luck in a changing city and a figure for herself. “In memory it seems as lustrous as a chambered nautilus’s mother-of-pearl shell, as though I was a hermit crab who had crawled into a particularly glamorous shelter . . . I dreamed many times about finding another room in it, another door. In some way it was me and I was it, and so these discoveries were, of course, other parts of myself.” Roaming the city in a leather jacket, scavenging furniture off the street, buying clothes from thrift stores, and using milk crates to hold her books and mixtapes, she began to take possession of herself.

The city nourished her, gave her friends and a sense of belonging. (It gave her lovers, too, though she keeps the men in her life offstage.) It was the site of her education, including a master’s in journalism at Berkeley and a vista-opening work-study job at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art. She wrote her first book on West Coast artists of the Beat era, who taught her by example how to live on the margins. From friends in San Francisco’s gay community she learned that gender rules could be broken and conventional partnerships aren’t the only way to live, that “a life can have as its stable foundation friendships so strong that they are a form of family.”

On the other hand—and this is her point—the city seemed determined to erase her. She loved walking after dark, believing, under the heady influence of Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, that “night is the space in which poetic intuition, not logic, prevails, in which you feel what you cannot see.” But at night, and even by day, she had hostile encounters with men, so that she had to become “expert at fading and slipping and sneaking away, backing off, squirming out of tight situations . . . absenting myself.” When she talked about these incidents she was often disbelieved by those who, for whatever reasons of privilege, luck, or reticence, had encountered less harassment. Her love of and fear of walking in the city were part of her energy as a writer: “I wanted to bring Barnes’s ferocious lyricism to my own immediate experience, to wed the poetics of what I wanted and the politics of why I had trouble reaching it. To whom does the night belong? It did not seem to belong to me.”

And so you armor yourself by doing what’s expected. “You learn to think of what you are in terms of what they want . . . and sometimes you vanish to yourself in the art of appearing to and for others,” Solnit writes, speaking not only for herself but for women in general. “The fight wasn’t just to survive bodily, though that could be intense enough, but to survive as a person possessed of rights, including the right to participation and dignity and a voice.”

The women’s movement could have taught her that, but she was caught up in other subcultures, especially the punk and art scenes, and didn’t think feminism was for her. In those days she had “no clear feminist ideas, just swirling inchoate feelings of indignation and insubordination,” and it wasn’t until she wrote the 2008 essay “Men Explain Things to Me” that she and it came together in what’s been a fruitful and passionate collaboration.

Ever since then she’s been playing catch-up. Solnit’s new book is a work of feminist solidarity, in which she chooses to write not from herself alone, but “for and about and often with the voices of other women talking about survival.” Sliding frequently from the personal into the general, in a sense she’s found a new way to leave herself out. This frustrates some of the ordinary pleasures of memoir: the personal drama and psychological insight of The Faraway Nearby aren’t here. Yet as Solnit pushes the boundaries of the genre, she shows that it’s wide enough to contain at one end the willful oversharing of Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, and at another this cool meditation on creativity, home, and an elusive self.

The writer James Hannaham once told me about a woman who, when a man tried to hit on her with the line “You’re not like other women,” snapped back, “Oh, yes I am.” Solnit’s refusal to be separated from others can be limiting: the polemicist sometimes gets in the storyteller’s way. But that she’s like other women is also what she needs to tell us—because it’s a new source of strength for her, and because it’s true.

Julie Phillips is the award-winning author of James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon. She lives in Amsterdam and is working on a biographical book about creativity and mothering, for which she received a Whiting nonfiction grant. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Ms., and the Village Voice, among others. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.