Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

In her playful sequel to A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan imagines an internet used for good.

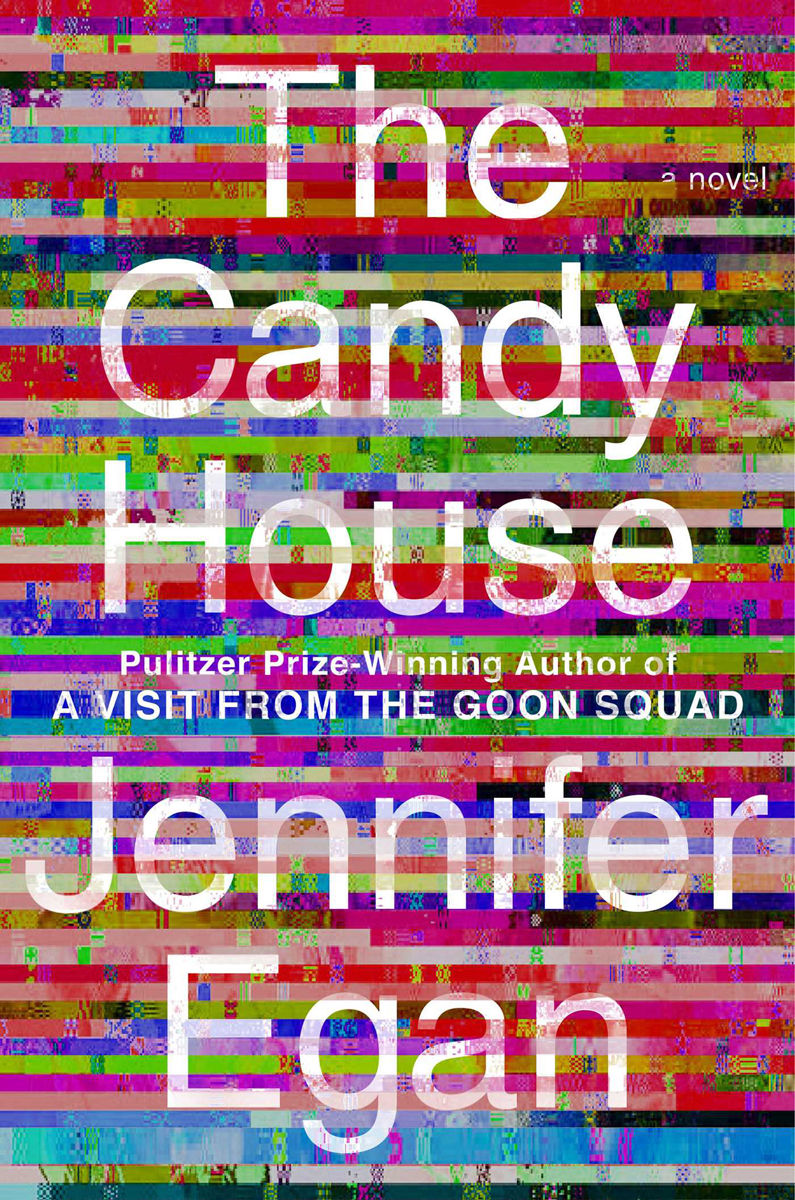

The Candy House, by Jennifer Egan, Scribner, 334 pages, $28

• • •

An image from Jennifer Egan’s The Candy House reflects the eclectic form and the electric excitement of this noisy, crowded, exhilaratingly inventive novel. One of its characters, Sasha, is an artist who makes sculptures out of discarded plastic in the California desert. Close-up, her pieces look like brightly hued heaps of ill-assorted objects, but seen from the air, they form lines of color that race joyfully across the ground, acquiring “structure and logic, like random scribbles aligning into prose.”

In its loosely connected structure and powerful thematic logic, The Candy House echoes Egan’s 2010 A Visit from the Goon Squad. It serves as a sequel, too, continuing the stories of Lou, the sleazy record producer; Benny, the punker turned music-industry executive; Sasha, the artist, who was once Benny’s kleptomaniac personal assistant; and her autistic son, Lincoln, who in Goon Squad loved and measured the pauses in rock songs. Where the earlier book used the music scene to explore selfhood and the passage of time, The Candy House employs social media for similar purposes, to talk about how people shape themselves in relation to each other and to their past.

The novel opens with tech guru Bix Bouton suffering from an emptiness he will later call “the Anti-Vision: a vacancy where a new idea refused to appear.” Seeking inspiration for his social media company, Mandala, he participates in a discussion group, reflects on an accident he witnessed years before, and has a revelation that leads him to create a new internet platform: Own Your Unconscious™, which allows users to access their own and others’ memories. More Mandala products follow, including MemoryShop™, for editing out traumas; Hey, What Ever Happened To . . . ?™, for searching others’ recollections; and most notably the Collective Consciousness, a vast database to which people can anonymously upload their experiences. All these are based on affinity algorithms developed by Miranda Kline, a legendary anthropologist who herself refuses to take part in this feast of connection. Miranda’s choice to hide her identity from the internet—to become an “eluder”—obliges even her own daughter to interact with her through a “proxy,” a bot so realistic its responses are hard to tell from Miranda’s own.

This might make Candy House sound like a dystopian futuristic gloomfest about the internet, but far from it. Though the narrative swings back and forth in time—opening in 2010, going forward to the 2030s, sometimes circling back in (uploaded) memory—it’s very much involved with the here and now. It’s also surprisingly optimistic. Miranda Kline’s daughter, the one who patented and monetized the affinity algorithms, cynically cites the danger of expecting gratis pleasure. “Nothing is free! Only children expect otherwise, even as myths and fairy tales warn us: Rumpelstiltskin, King Midas, Hansel and Gretel. Never trust a candy house!”

But the potential of the Collective Consciousness to erode the self, enable corporate greed, or undermine democracy appears less interesting to Egan than its uses for good. The benefits of Own Your Unconscious™, we’re told, include “Alzheimer’s and dementia sharply reduced by reinfusions of saved healthy consciousness; dying languages preserved and revived . . . and a global rise in empathy that accompanied a drastic decline in purist orthodoxies—which, people now knew, having roamed the odd, twisting corridors of one another’s minds, had always been hypocritical.”

With people’s former selves stored in Consciousness Cubes, time’s passing isn’t the tragedy that it was in Goon Squad. Instead the clock shows a kinder face, healing wounds and yielding self-awareness. Lana and Melora, Lou’s youngest daughters, help that middle-aged ball of id grow into the role of their father. Benny’s ex-wife Stephanie negotiates the suburban social stresses of country-club friendships. Stephanie’s unstable brother Jules, in a conflict with his neighbor about a property line, learns the value of physical and emotional boundaries. Roxy, another of Lou’s daughters and a recovering addict, plays Dungeons & Dragons with Benny’s son Chris, a recovering tech employee. The stories end happily for the most part, with the heart triumphing over oddness and anomie.

There’s nothing wrong with understanding behavior through algorithms, Sasha’s son Lincoln argues. He has become a “counter,” whose job is to track and quantify the behavior of individuals within the collective. Yet he feels this doesn’t lead to exploitation; on the contrary: “Quantifiability doesn’t make human life any less remarkable, or even (this is counterintuitive, I know) less mysterious—any more than identifying the rhyme scheme in a poem devalues the poem itself.” He himself is obsessed with a mysterious quantity, x, defined as the one thing that will make his coworker return his attraction, “that ineffable, unpredictable detail that makes one person fall in love with another person.”

Like the entertainment start-up she describes, whose product is equations for generating plots, Egan has a remarkable facility for coming up with characters and stories. Where the form of her previous book, the historical novel Manhattan Beach (2017), constrained that side of her gifts, much of the fun of The Candy House is in seeing her use them to the full. Some of her stylistic experiments here are original, some moving, others clever but unconvincing, like her pastiche of a spy thriller or the chapter that ties all the loose ends together in a thread of old-fashioned emails. That’s not a complaint: with a book this playful and brilliant, readers’ mileage is always going to vary. And ultimately, its shape and its subject matter come together brilliantly.

Starting with Neuromancer and proceeding through The Matrix, fiction about the internet has often been about who you are when you’re on it: what part of yourself is projected into the collective and what that means for the nature of the self. In her final chapter Egan spells out what has been clear from the start, that what she’s really writing about—as she plays with thoughts about authenticity, counting, storing one’s memories in a Consciousness Cube, and experiencing those memories as an observer—is the power of the novel to record, predict, respond to, and shape experience. The candy house the characters really want, she seems to say, is their own humanity, and fiction is the path to its door.

Julie Phillips’s book The Baby on the Fire Escape, on mothering and creative work, will be published in April 2022.