Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

“Childhood is long and narrow like a coffin”: the memoirs of Danish poet Tove Ditlevsen.

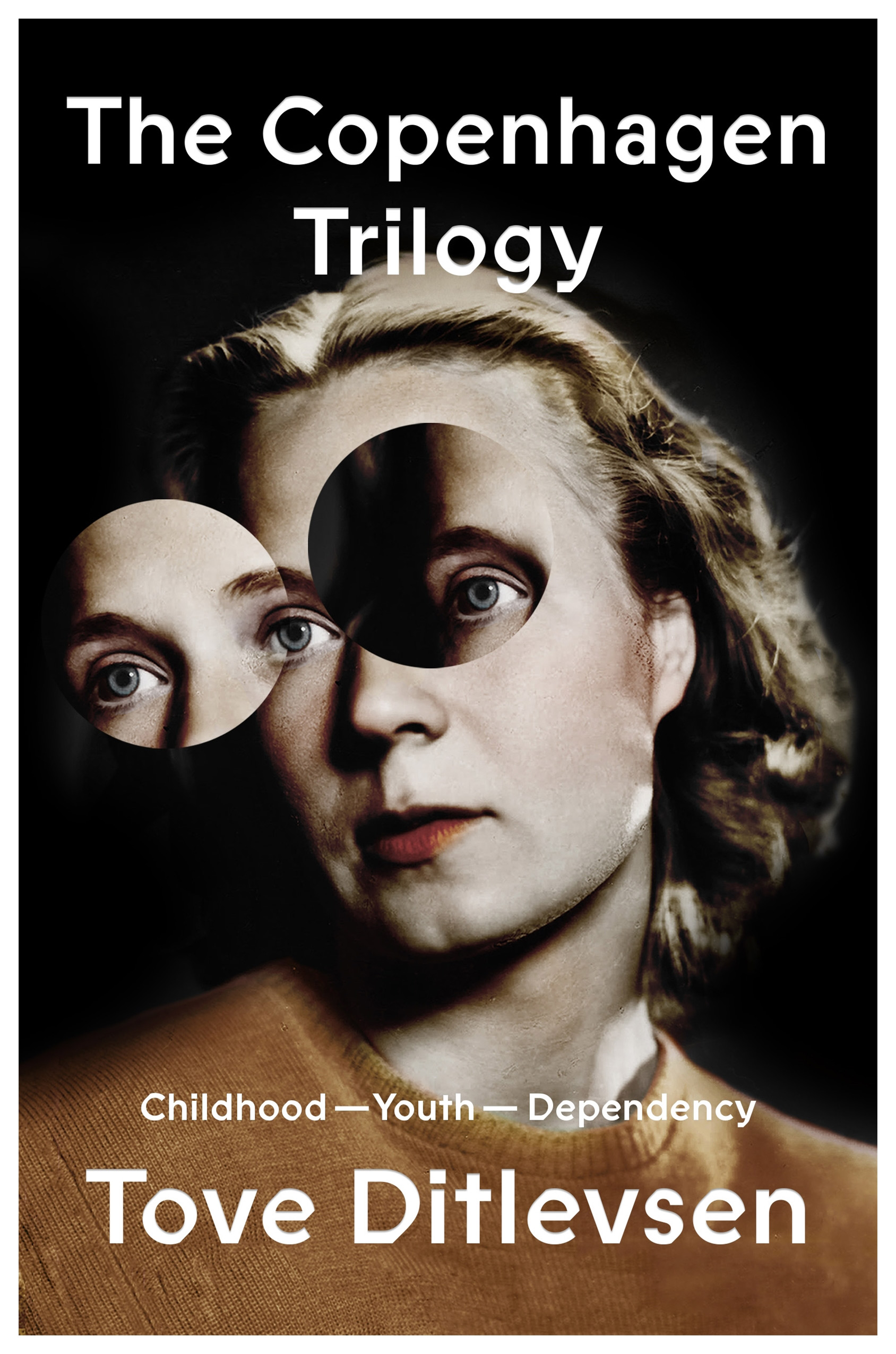

The Copenhagen Trilogy: Childhood; Youth; Dependency, by Tove Ditlevsen, translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 370 pages, $30

• • •

No one has written about childhood quite as memorably as the Danish poet Tove Ditlevsen, or described the compulsion to write with so much hope and foreboding. Her memoirs of growing up in working-class Copenhagen before the Second World War read like Ferrante meets Fierce Attachments, Vivian Gornick’s psychologically insightful memoir of maternal entanglement. But Ditlevsen’s brooding lyricism is all her own as she recalls the inner life of a sensitive child trying to parse her surroundings, comprehend an overwhelming, illogical mother, and appease her own exigent, unlikely gift.

“In the morning there was hope. It sat like a fleeting gleam of light in my mother’s smooth black hair that I never dared touch,” Ditlevsen begins. Little Tove thinks that if she can only stay still enough, her mother won’t notice her and her mood won’t turn ugly. If it does,

when hope had been crushed like that, my mother would get dressed with violent and irritated movements, as if every piece of clothing were an insult to her. I had to get dressed too, and the world was cold and dangerous and ominous because my mother’s dark anger always ended in her slapping my face or pushing me against the stove.

Her three memoirs, Childhood, Youth, and Dependency—the first two out of print in English, the last never before translated, all newly published in one volume—are partly a history of thwarted love and the attempt to read a mother whose feelings are a mystery even to herself.

They’re also a recollection of poverty, manifested in the crowded rooms and narrow minds of her neighborhood, Vesterbro. Her imagination lets her escape from the family’s cramped apartment but not the implausibility of her own existence.

Wherever you turn, you run up against your childhood and hurt yourself because it’s sharp-edged and hard, and stops only when it has torn you completely apart. It seems that everyone has their own and each is totally different. My brother’s childhood is very noisy, for example, while mine is quiet and furtive and watchful. No one likes it and no one has any use for it.

Indelibly, she writes, “Childhood is long and narrow like a coffin, and you can’t get out of it on your own.”

Most of all these are the memoirs of a young writer struggling to make a place for her extraordinary perceptions. Tove’s imagination and inquisitiveness cause people to think her stupid, a mask she learns to hide behind for safety’s sake. By fourteen, self-concealment has come uncomfortably close to self-denial: “I don’t seem to own any real feelings anymore, but always have to pretend that I do by copying other people’s reactions.” Her one friend, Ruth, is not her fated ally like Lila is for Ferrante’s Lenù, just a partner in practicing adulthood: “I make myself into her echo because I love her and because she’s the strongest, but . . . I feel as if I’m deceiving her by pretending that we’re of the same blood.”

The Copenhagen Trilogy is being acclaimed as a recent discovery, but there are sentences in Childhood and Youth that have been furnishing my mind for years. Those two books were first published in English in the 1980s, in Tiina Nunnally’s fine translation, in one out-of-print volume titled Early Spring. In her native country, in any case, Ditlevsen has had enduring acclaim. Born in 1917, she started young, publishing poems in her late teens. She published her first poetry collection at twenty-one and her first novel two years later. Her literary reputation was recently summed up by the Danish writer Dorthe Nors as “loved by generations of women and put down by generations of men.” Her career was productive, though marked by struggles with depression and addiction, until it ended with her suicide in 1976.

She published her memoirs in three parts, from 1967 to ’71, completing the trilogy with Dependency, whose Danish title, Gift, means both “Married” and “Poison.” (The translator of this last book is Michael Favala Goldman.) Growing into adulthood as a writer and a woman, Tove finally makes friends and discovers her people. Love is a problem for her, though, one as irritating as it is all-consuming. Although she marries and has a child, she can’t figure out how to be a wife while she’s distracted by the lines of poetry that keep forming in her head. She loves her husband, she says anxiously, “but not in the right way. If he forgets his scarf, I don’t remind him. I don’t go out of my way to make nice food for him or anything like that. . . . When I’m writing I don’t care about anyone.”

She has no idea how to preserve in marriage the solitude and boundaries she needs to write. Intuitive and sensitive, she lacks the political savvy and protective cynicism of a Mary McCarthy or Doris Lessing. She’s more a Marguerite Duras, Clarice Lispector, or Shirley Jackson, who took to drink, drugs, and destructive relationships to cope with the irreconcilable demands of love and their art. Dependency chronicles the emotional chaos Tove created in her twenties, leaving one husband for the next—there are four in all—whenever a marriage became confining. Clearly it’s only within the sheltering clouds of emotional turmoil that she could make a space for her art and her writing self.

Chaos has consequences: she ends up with an abuser, a controlling doctor who gets her addicted to Demerol. Dependency offers a painful chronicle of her years as a suburban opioid addict. “I sleep; I wake up; I’m sick or I’m well. I see my typewriter in the distance, as if I were looking backwards through binoculars.” Eventually she leaves and her head clears, yet there’s something blurred about her tale of this period: the conditions of her life as a woman are never entirely clear to her. Writing remains for her what it was as a child, a masked activity, “something secret and prohibited, shameful, something one sneaks into a corner to do when no one else is watching.” Though Tove escapes from Vesterbro, she can escape from herself only momentarily, into the brilliance of the sentences that wouldn’t let her go.

Julie Phillips is the award-winning author of James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon. She lives in Amsterdam and is working on a biographical book about creativity and mothering, for which she received a Whiting nonfiction grant. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Ms., and the Village Voice, among others. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.