Margaret Sundell

Margaret Sundell

Revolutions in art and life.

Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented, installation view. © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt.

Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented, organized by Jodi Hauptman and Adrian Sudhalter with Jane Cavalier, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through April 10, 2021

• • •

In the latter half of Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented, at the Museum of Modern Art, an imposing image draws the eye. Let’s Fulfill the Plan of Great Works was created in 1930 by Gustav Klutsis—one of the key figures of the Soviet avant-garde. The title is printed in a bold diagonal on a rousing red ground. Intersecting the legend at an opposing angle is a single, giant outstretched hand containing masses of identically outstretched ones at a much smaller scale. The composition, while forceful, is extremely stable: the words and hands together form a commanding X. This is an image of absolute solidarity and singular authority.

Gustav Klutsis, Let’s Fulfill the Plan of Great Works, 1930. Lithograph, 46 5/8 × 33 inches. © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource.

Such monumentalist propaganda evolved from vertiginous images that came as close to spinning out of control as modern life itself. In the tumultuous period following World War I and the Russian Revolution, the avant-garde approached its dream of breaking down the boundaries between art and the everyday. And nowhere is their aspiration more fervently revealed than in The Artist Reinvented, which spans the period from 1918 to 1939 and focuses on Germany and the Soviet Union (with pit stops in Italy, the Netherlands, and Eastern Europe).

As the exhibition’s title suggests, if the work of art was to be reimagined, so too was its author. No longer cut off from the world, facing an easel alone in an atelier, the artist would renounce painting, abandon the studio, and absorb the lessons of a reality newly wrought by modernization. We learn from the show’s introductory text that German Dadaist Hannah Höch regarded herself and her peers less as artists in the traditional sense than as engineers: putting “works together like fitters.” “The artist is a constructor,” declared Soviet writer Osip Brik. This notion bespeaks a crucial feature of the artist’s redefined role: she would not simply bring art into life but be an active participant in forging the latter; her work was aimed at social change. The use of the feminine pronoun is pointed here. Expanding the traditional role of the artist untethered it from its masculine orientation. The large number of women represented in The Artist Reinvented attests to that liberatory fact.

While profound, the recasting of artistic identity that took place in the opening decades of the twentieth century also serves, for the show’s purposes, as something of a conceit—a way of corralling the sprawling gift of more than three hundred works from the Merrill C. Berman collection that occasioned The Artist Reinvented. There’s a blowsy quality to its organization: some walls are devoted to works by particular artists, others thematically emphasize the uses to which their new art was put (propaganda, advertisement, publication design, etc.). By the end of the show, things seem slightly random: following displays of “Public Address” and “New Ways of Living” comes a final niche addressing “Models of Resistance.” These categories are a way of breaking down the sheer volume of works on display. Their lack of cohesion is to be forgiven, and their accompanying wall text should be assiduously read: without it, one misses crucial historical anchors.

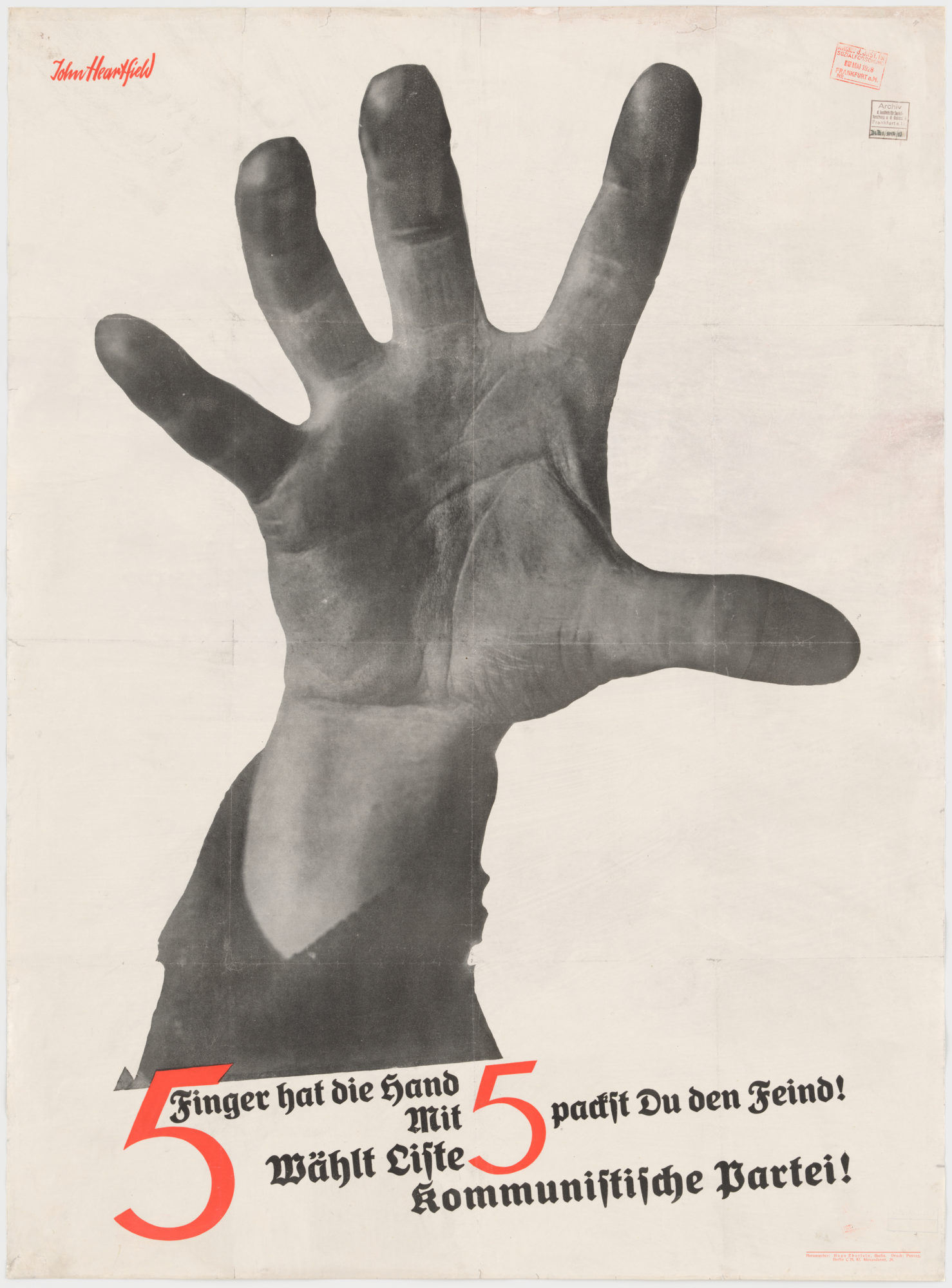

John Heartfield, The Hand Has Five Fingers (Campaign poster for German Communist Party), 1928. Lithograph, 38 1/2 × 29 1/4 inches. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.

One, entitled “Photomontage,” describes the dramatic increase in illustrated magazines after World War I. Suddenly images were everywhere; they felt more accessible, more available—ready to be excised. (Photographs were also staged, as in John Heartfield’s The Hand Has Five Fingers, 1928, which shows an open, grabbing fist that seems to hurtle to the front of the picture plane.) Extending the cut-and-paste practice of collage, photomonteurs created clashes of site and scale in an effort to capture both the fragmentation and dynamism of the world around them. An important weapon in the fight to bring art and everyday life into the closest possible proximity, photomontage is well represented here.

Hannah Höch, Untitled (Dada), c. 1922. Cut-and-pasted printed and colored paper on board, 9 3/4 × 13 inches. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.

There are also pieces on view that eschew photographs while adhering to the broader principles of collage-montage. Many of these feature letters, unbound and set at jaunty angles or composing rapid-fire texts. Höch, for instance, presents an off-centered shard of newsprint that reads “dada”—the moniker for an art meant to blast open tradition in all its forms. The word juts out from an unsettled ground composed of colored paper, bits of print from disparate sources, even a postage stamp. In works meant to be read as much as seen, text has an explicitly communicative function: Klutsis’s Let’s Fulfill the Plan of Great Works, for example, is a clear reference to Stalin’s five-year plan. Text is one point where the differing stakes of art in varied countries becomes clear. In Germany, artists intervened into a modern life marked by the vicissitudes of capitalism and the rise of fascism; in the Soviet Union, they were actors in a revolution, using mass media, frequently posters, to disseminate missives from the new society they were helping to build.

Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented, installation view. © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Robert Gerhardt.

In the case of certain Soviet posters, curators Jodi Hauptman and Adrian Sudhalter exhibit diminutive maquettes alongside the finished product. There’s something thrilling here, and it’s not just the peek into the maker’s process. It’s also the fact that in turning to forms like posters, the avant-garde created artworks that were conceived from the outset to be mass-reproduced. And those reproductions are notable for being images presented in the public sphere, experienced not by individuals but by crowds, and not with the reverence typically accorded to art but perhaps even in a state of distraction. This was a seismic shift—from the singular artwork to the open-ended multiple, from individual to collective reception, from rapt absorption to off-handed viewing. At the time, it felt like a revolution in form that both mirrored and reinforced the revolution taking place in life.

Little could these Soviet artists foresee that capitalism would eventually find a way of commodifying even the most radically democratized and dematerialized art through the workings of the experience economy. And in any case, they had other, more immediate tragedies to contend with, as did their counterparts in Germany. Soon, the Nazi party would deem the work of Höch and her fellow Dadaists “degenerate”—an epithet they equally extended to its makers. In Russia, the production of posters was centralized in 1931 so that they could be more easily reviewed—and censored—by the increasingly repressive Stalinist regime, which in a few years would jettison the avant-garde altogether in favor of the idealizing genre of Socialist Realism. As the wall text bluntly notes, “despite his years of service, Klutsis was executed in 1938 for being an ‘enemy of the state.’ ”

Margaret Sundell is the editor-in-chief of 4Columns.