Julie Phillips

Julie Phillips

Cyberpunks and the battle against patriarchy in a new anthology of women-authored science fiction from the ’70s.

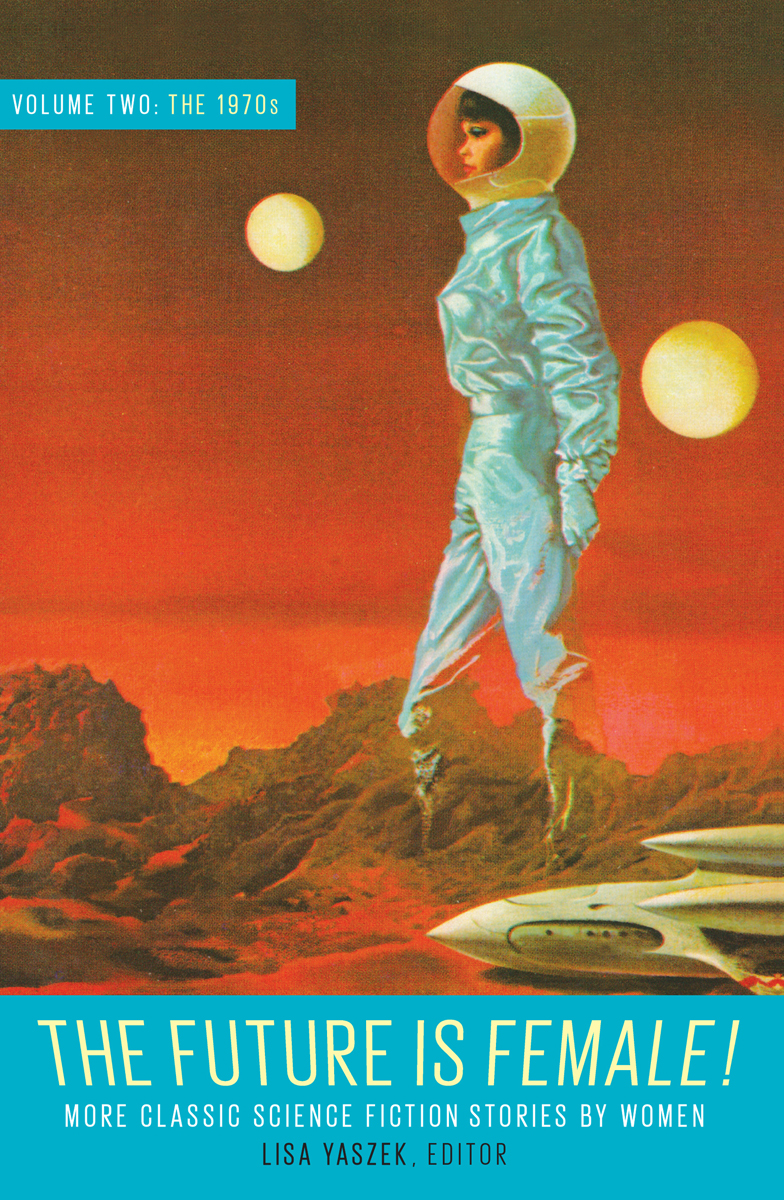

The Future Is Female! Volume Two, the 1970s: More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women, edited by Lisa Yaszek, Library of America,

490 pages, $27.95

• • •

A good feminist argument generally ages well, and no surprise. Despite the changes of the past half-century, human beings are still stewing in an immemorial broth of angst and aggro around gender, adding dashes of contraceptive technologies and reproductive rights now and then and giving it a stir. In her radical Dialectic of Sex (1970), Shulamith Firestone called for feminists to revolt and take control of the means of (re)production, including all the institutions of childrearing. While you’re waiting for that plan to succeed, you can reread Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which has yet to be surpassed as an argument because it too has yet to be fulfilled.

Feminist polemics give birth to feminist dreams. Wollstonecraft’s daughter Mary Shelley wrote the first science-fiction novel, Frankenstein, in 1818, and the genre has been rethinking nature and society ever since. What do women want to see in the world? Economic, racial, and climate justice; nonbinary thinking; and extraordinary ways of conceiving and raising children are among the subjects of recent female-authored science fiction. Also on offer are noncolonial alternate history, time-traveling lesbian epistolary romance, and all kinds of possibilities for the self.

Science fiction came of age at the intersection of modernity and technology, in a creative space shaped by new capabilities (space travel) and dangers (nuclear holocaust). Second-wave feminism generated even more imaginary futures (and, when history was looked at afresh, new pasts). The short stories in The Future Is Female chronicle the intensity of that combative and utopian movement.

For this volume—part two in a collection of SF by women, published by the Library of America—Lisa Yaszek, a professor of science fiction at Georgia Tech, has chosen twenty-three texts published in the 1970s, looking in particular at stories centered on female experience. The worlds they take place in are idealized or dystopian, but Yaszek’s focus is on the metaphors SF writers use to explore individual potential. Some tales depict heroic or exotic selves—a spy liberating a city in Marta Randall’s “A Scarab in the City of Time” (1975), a teenage girl adapted to survive a poisoned environment in Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s “Frog Pond” (1971). But as the incomparable Joanna Russ observed, the power of fantastic imagery is in its ability to express the day-to-day difficulties of human life. The haunted mansion stands for an abusive partner, the vampire reminds you of your emotionally draining housemate, the alien is you.

Women are both alien and the norm in Russ’s classic “When It Changed (1972),” one of the standout stories in the collection. Like Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 Herland, it envisions the arrival of men in an all-female world. But Russ’s planet Whileaway is no utopia founded on female kindness. She crafts a complex society with room for women’s whole selves, in all their impatience, rivalry, and ambition.

The story’s narrator, describing her daughter, writes:

Yuriko, my eldest, was asleep in the back seat, dreaming . . . of love and war: running away to sea, hunting in the North, dreams of strangely beautiful people in strangely beautiful places, all the wonderful guff you think up when you’re turning twelve and the glands start going. Some day soon, like all of them, she will disappear for weeks on end to come back grimy and proud, having knifed her first cougar or shot her first bear.

The right to face danger, to be brave, to be alone, is what the narrator fears losing should men regain control.

In several of the stories, men pose a hazard to women. Kate Wilhelm’s 1972 “The Funeral” anticipates Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) in picturing women stripped of their rights and girls taught subservience to men. The bleakest entry in the collection is probably “The Screwfly Solution” (1977), by Raccoona Sheldon, in which a slight hormonal change turns male sexual desire into bloodlust and men all over the planet feel an uncontrollable need to murder their partners. Some justify the slaughter as a cult of purity: “When man gets rid of his animal part which is woman, this is the signal God is awaiting. . . . Man must purify himself and show God a clean world.” As Russ wrote, it’s terrifying because it’s true.

The women portrayed here especially struggle to be themselves in the context of heteronormative desire. James Tiptree, Jr. (a pseudonym, like Raccoona Sheldon, for the writer Alice Sheldon) is represented by “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” (1973), an early cyberpunk tale in which a woman is destroyed by a man who sees in her his feminine ideal. In Sonya Dorman Hess’s surreal “Bitching It” (1971) a group of seemingly ordinary homemakers turn out to have the shameless sexuality of dogs. In the moving, unnerving “Daisy, in the Sun” (1979), by Connie Willis, a pubescent girl’s disgust for and disquiet with the changes in her body are expressed in dreamlike images of the sun’s extinction.

The future in these stories is for the most part white and cishet. Octavia E. Butler couldn’t be included due to permissions issues (though she has her own Library of America series), and her absence diminishes the collection. In some ways these tales feel bleak and narrow next to exuberant, inventive recent SF like N. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became (2020), in which the boroughs of New York City develop BIPOC avatars, and Martha Wells’s Murderbot Diaries series (beginning with All Systems Red, 2017) about an ungendered android with an identity crisis.

The one entry in this volume that describes women, and offers hope, in anti-capitalist terms is not surprisingly the one that still feels farthest from reality. In Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Day Before the Revolution” (1974), the great socialist-anarchist theorist Laia Odo lives out her last day of life looking back on the change she helped to shape. She won’t live to see the means of production seized, and she’s impatient with the young activists who put her on a pedestal. But she envies them the cultural transformation that they’ve already accomplished. “They had grown up in the principle of freedom of dress and sex and all the rest, and she hadn’t. All she had done was invent it. It’s not the same.”

Inventing change isn’t the same as making it, and many of the other stories in the book feel embattled, all too aware that they’re competing with rival fantasies of women’s inferiority. The freedom they offer is limited and contingent, the backlash lying in wait. But many of the best have a quality that was most recently visible in the film Everything Everywhere All at Once: a sense of domestic doldrums existing alongside an endless possibility that feels both necessary to psychic survival and a joy to discover on the page.

Julie Phillips’s most recent book is The Baby on the Fire Escape, on mothering and creative work.