Barbara Pollack

Barbara Pollack

Testing the limits of the permissible: the Guggenheim surveys twenty years of a nation’s contemporary art.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, installation view. Photo: David Heald.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through January 7, 2018

• • •

1989 was a pivotal year in world history: the Berlin Wall fell, South Africa witnessed the beginning of the end of apartheid, and the World Wide Web was invented. In China, after months of protests in Tiananmen Square, the pro-democracy movement was brought to a bloody end when government troops fired on the crowds, initiating an official crackdown on free expression in all areas of culture and society. The year is thus an apt starting point for the Guggenheim’s ambitious new survey, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, which traces the development of contemporary Chinese art from the aftermath of Tiananmen to the media blitz of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics.

1989 was also a pivotal year in my life, as the culture wars hit home. Senator Jesse Helms and a right-wing coalition declared war on the NEA for its support of such boundary-pushing art as Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, and the Corcoran—afraid of pouring gasoline on the already fiery debate—cancelled a long-planned Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective. At the time, I was working in New York City at Franklin Furnace, a hub of performance art and a bastion of rebellion, where a lineup of LGBTQI artists and Dada-inspired resisters countered these attacks day after day. In this crash course in the First Amendment, I viscerally experienced what it feels like for art to be deemed unacceptable by government officials.

Which led me to be predisposed to Chinese artists—a population working under the constant threat of censorship—when Inside Out: New Chinese Art came to Asia Society and PS1 in 1998. I was amazed by what I encountered. These artists—ambitious and eager to participate in a global dialogue—appeared to have thrived despite government restrictions. Thus began my investigation into contemporary Chinese art, which, over the course of the last twenty years, has resulted in countless interviews and articles, two books, as well as cherished friendships with many Chinese artists.

Zhang Peili, 30 × 30, 1988. Color video, with sound, 32 minutes, 9 seconds. Image courtesy Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

So I was eager to see Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, which promised to offer a new look at this field, framed by China’s unparalleled growth from 1989 to 2008 from a primarily rural and isolated country to a world superpower. The curators—Alexandra Munroe, Philip Tinari, and Hou Hanru—have selected predominantly conceptual artworks that slyly comment on China’s massive transformation during this period while testing the limits of what is permissible. In the process, they also found that three artworks—by Huang Yong Ping, Xu Bing, and Beijing duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu—were not acceptable, even in present-day New York City. (More on that in a minute.)

Almost entirely absent from Art and China are two painting movements—Cynical Realism and Political Pop—those darlings of the auction houses that have dominated all prior attempts at establishing a canon of recent Chinese art. Steering clear of popular paintings that merge Andy Warhol with Cultural Revolution iconography, the Guggenheim survey commendably emphasizes thought-provoking projects, encouraging viewers to appreciate that many Chinese artists are intellectuals, not makers of commercially viable objects.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, installation view. Photo: David Heald.

For example, the exhibition emphasizes the role of artist collectives, starting with the 1990s New Measurement Group, which made use of abstract diagrams to critique officious government regulations, and ranging to Art-Ba-Ba, an artist-initiated platform for online discussions about art in China, founded in 2006. A show-within-the-show is the exhibit’s history of video art, from Zhang Peili’s exercise in futility, 30 x 30 (1988), the first example of video art in China, in which the artist breaks a mirror and pastes it back together, over and over again, to Yang Fudong’s haunting tale of an alienated young man, An Estranged Paradise (1997–2002), to coverage of Cai Guo-Qiang’s fireworks design for the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. Few women flourished in China’s male-dominated art academies. (Only ten of the seventy-one artists on display here are women.) But Lin Tianmiao makes an impression with her installation Sewing (1997), a sewing machine wrapped in cotton thread with a video of the artist hemming a garment, and Cao Fei contributes RMB City (2007–11), a futuristic interactive work made shortly before she was named a finalist for a Hugo Boss award in 2010.

Cao Fei, RMB City: A Second Life City Planning by China Tracy (aka: Cao Fei), 2007. Color video with sound, 6 minutes. © Cao Fei.

A highpoint of the exhibition is the section titled “Uncertain Pleasures: Acts of Sensation,” which covers the 1990s predilection for nudity and experimentation in enclaves such as Beijing’s East Village, a rundown, poverty-stricken neighborhood that attracted artists, performers, poets, and all other sorts of bohemians. Ai Weiwei is placed in proper context here as a key organizer, bringing back information from New York’s East Village—where he lived from 1983 to 1993—publishing interviews with emerging performance artists such as Zhang Huan (who sat in a public toilet and let flies gather on his honey-covered skin), and making his own statement about destroying traditions to pave the way for new ideas by smashing a valuable Han Dynasty urn. Rare film footage of a group of artists, naked, piled up on top of one another in a mountainous landscape, form a tableau best known from the photograph To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain (1995). Operating entirely without a gallery system, these artists were their own—and only—audience. The extreme, at times intentionally shocking, nature of their work attests both to the artistic freedom such a situation allowed and the frustration it engendered.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, installation view. Photo: David Heald.

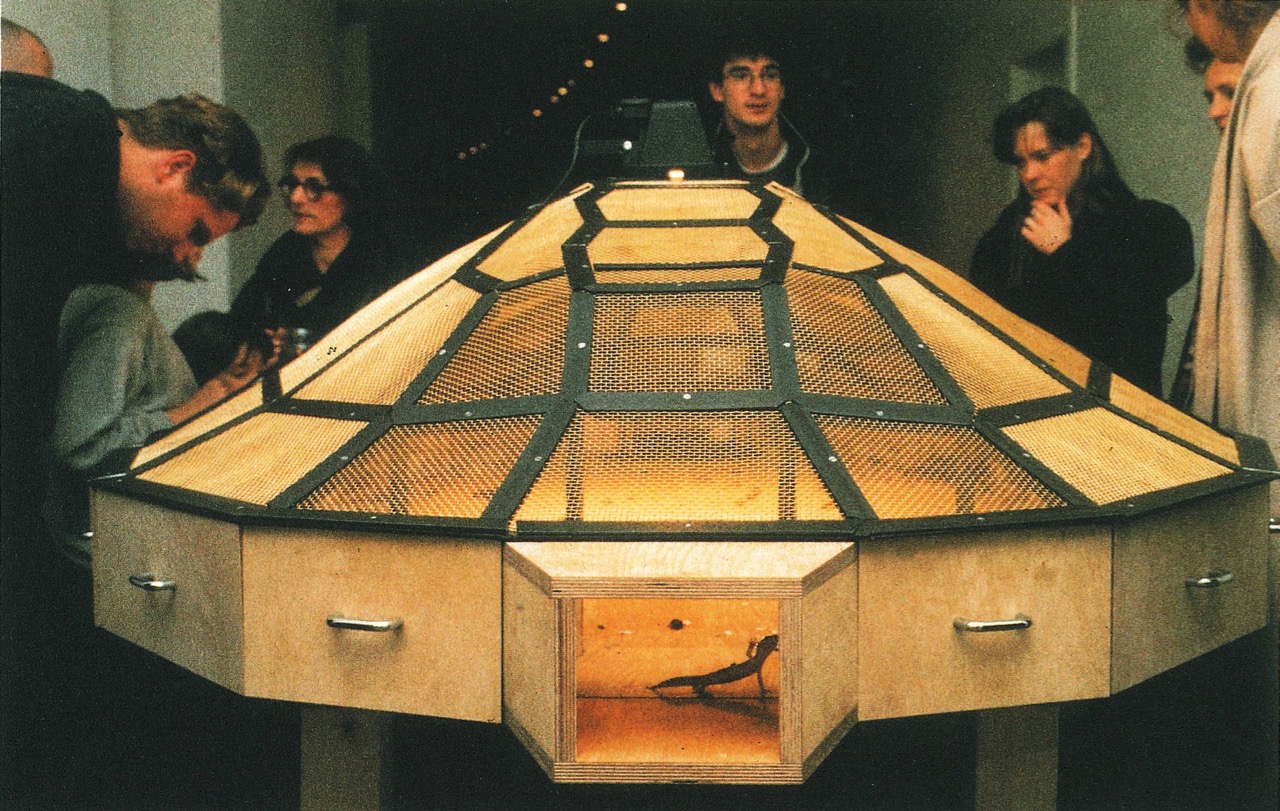

Chinese art from this period still has the ability to shock, as proven by the controversy that erupted just days before the exhibition was scheduled to open. All three of the works involved featured the use of animals: Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World (1993), a cage-like structure that was supposed to hold live insects and reptiles who would devour each other over the course of the exhibition; MacArthur winner Xu Bing’s video documentation of his performance piece, A Case Study of Transference (1994), which captures two pigs, one marked with nonsensical English letters and the other marked with incoherent Chinese characters, fornicating; and most troubling of all, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003), a film showing pit bulls chained to treadmills, straining to fight each other, in perpetual frustration. The Guggenheim responded to a petition of over 700,000 signatures and threats of violence by effectively removing them from the exhibition, leaving Theater of the World empty, Xu Bing’s video monitor dark, and Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s work frozen on the title screen.

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World, 1993. Image courtesy Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, © Huang Yong Ping.

These instances of silencing within the exhibition evoke the obstacles and isolation faced by so many Chinese artists of this period, as no wall labels or archival material manage to do. Whether we blame social media or museum administrators, this is undeniably an act of censorship, depriving the public from discovering the extremes, however disturbing, to which Chinese artists went in response to their isolation. Hopefully, this controversy will not drown even more voices by discouraging people from visiting the exhibition. This is a show worth seeing multiple times, with many artists overdue for recognition by American audiences. For decades curators have dreamed of a truly global art world. This exhibition proves that Chinese artists undeniably framed that vision, reinterpreting conceptual art practices and contributing artistic innovations of their own.

Barbara Pollack is the author of Brand New Art from China: A Generation on the Rise (I.B. Tauris, 2018) and The Wild, Wild East: An American Art Critic’s Adventures in China (Timezone 8, 2010). She is also the curator of My Generation: Young Chinese Artists (2014–15), as well as We Chat: A Dialogue in Contemporary Chinese Art (2016). Pollack has received two grants from the Asian Cultural Council and the Andy Warhol | Creative Capital Arts Writers Grant.