Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

Elevator Repair Service hits the fast-forward button on Shakespeare.

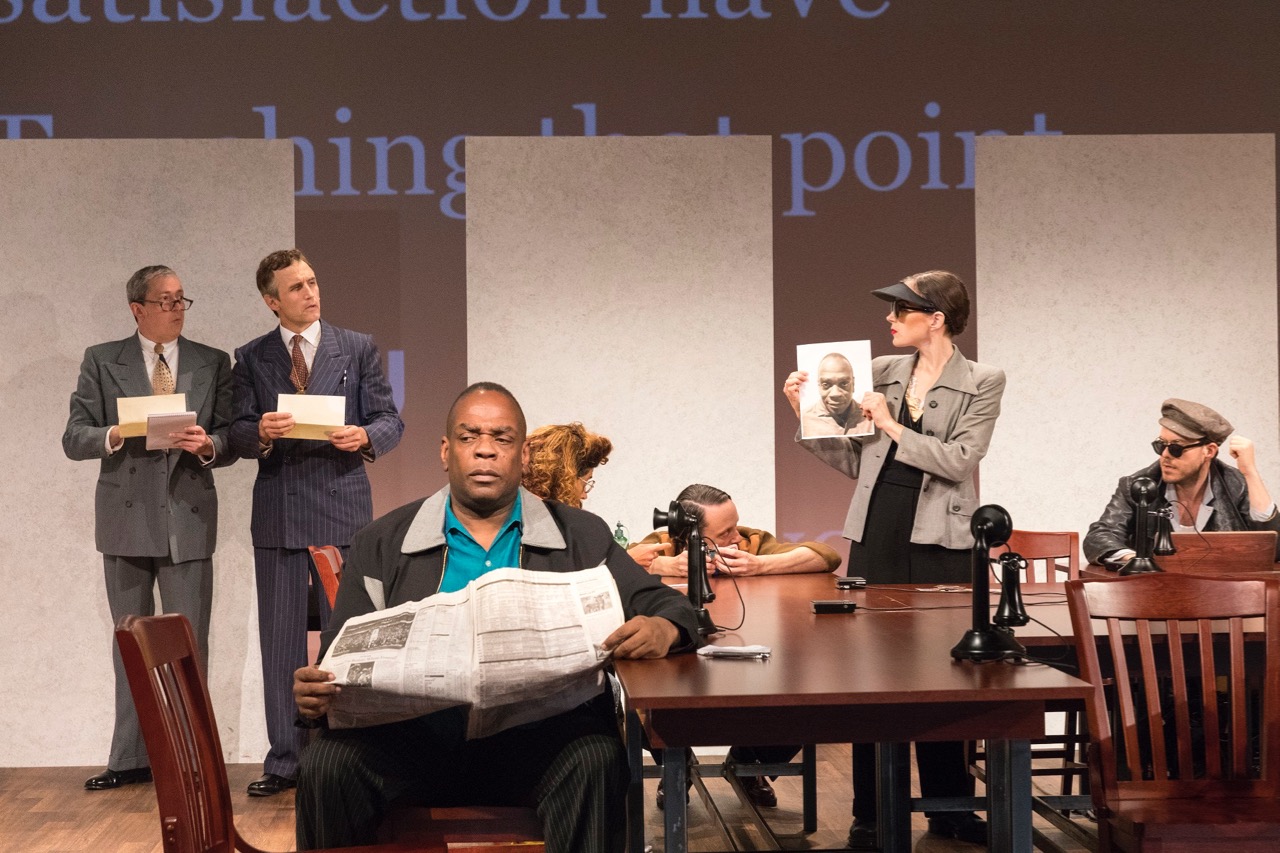

The company of Elevator Repair Service’s Measure for Measure. Photo: Richard Termine.

Measure for Measure, by William Shakespeare, the Public Theater, 425 Lafayette Street, New York City, through November 12, 2017

• • •

There’s a famous gag about the fallacy of infinite regress—supposedly told by Bertrand Russell—in which an old lady disagrees with a lecturing Copernican. The universe, she swears, is actually a plate on top of a giant turtle. The scientist asks her what the turtle stands on. “It’s turtles,” she tuts. “Turtles all the way down.” Trying to think about an Elevator Repair Service show can feel like struggling with that old lady. The production’s clearly a tissue of nonsense; you know the argument is screwy. But when an ERS piece works, it’s actually because of the earnestness of its own absurdity. At the existential level, it’s jokes, jokes, jokes. It’s jokes all the way down.

ERS is an experimental company—which in this case means experientially slippery, intentionally odd, gleefully shambolic. The troupe is interested in deconstructing texts, sometimes cutting them apart, or layering them, or in one case, making a new one out of passages from Supreme Court documents. ERS usually has a taste for top-flight literary material, but onstage, director John Collins and the company play with intentional “badness.” Costumes seem pulled from rehearsal gear. Props are goofy. And acting styles range from the staggeringly precise to the stunned quality of a deer in headlights. Given that, what may seem strange to their long-time fans is that the show now at the Public Theater is a relatively complete, if screwball-inflected, production of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. This time the jokes remain on the surface; the company’s weird mischief hasn’t penetrated to the play itself. The production is hectic, certainly, but it lacks the insouciant brio of their other pieces. If you haven’t seen an ERS show before, don’t start here.

The company of Elevator Repair Service’s Measure for Measure. Photo: Richard Termine.

The company has made several incredible pieces in the past: its strongest work has been with gonzo playwrights (Sibyl Kempson’s Fondly, Collette Richland) or low-fi literature adaptations (Gatz from The Great Gatsby). The destabilizing jokiness of their methodology requires a kind of counterweight from the script. A text doesn’t need to be conservative or traditional, far from it. But it must be a match of equals: the text will have to fight the Repair aesthetic at every step. Gatsby fought their anti-spectacular impulses with lyricism; Richland fought their mugging and vamping with a kind of neo-Joycean word-storm. The Repair Servicers are theatermakers-as-boxers—choosing projects for their difficulty, sparring with heavyweights of capital-C Culture, then performing the round punch-drunk and giggly. But in the fight with Measure, they seem somehow unsure of their opponent. They refuse to hit hard; Shakespeare’s got ’em on the ropes.

Now, every Shakespeare play isn’t a winner. Measure can be glum and confused, and it leaves a foul taste behind. It’s famously a “problem play,” which means its cynical justice-for-sex worldview seems depressingly modern while its language isn’t as quotable as Hamlet’s. The Duke of Vienna (Scott Shepherd) turns over government of the city to the prudish Angelo (Pete Simpson)—the cowardly Duke wants law-and-order Angelo to enforce the rules he has let lapse. When Angelo promptly sentences beloved local Claudio (Greig Sargeant) to death for sex outside of marriage, Claudio’s nun-in-training sister Isabella (Rinne Groff) turns up to beg for mercy. Bang! Angelo goes insane with lust—Simpson spins his chain of office ’round his neck like a hula-hoop—and demands Isabella’s virginity in payment for her brother’s life. Little does either of them know that the Duke is sneaking around, watching from the shadows, quietly “helping” while dressed as a monk. Hijinks! Zany! And yet it’s a bleak play. Every vow is upended, all courage fails, all bonds break.

The company of Elevator Repair Service’s Measure for Measure. Photo: Richard Termine.

The troupe has shifted Measure’s setting from seventeenth-century Vienna to a reporters’ bullpen at a 1930s newspaper. The set’s many long wooden tables have been sprinkled with antique bell-and-stem telephones, and, in the play’s strong first scene, exposition comes down “the wire,” the voices sounding as compressed and tinny as an olden-timey radio broadcast. Angelo and the Duke sport double-breasted suits; Isabella has seams in her stockings. (There’s also a rubber monster mask, but that’s just the anything-on-the-playground ethos at work.) To crank the performance speed to screwball levels, director Collins and actor/software-designer Shepherd have put the text on teleprompters, then they ratchet up the pace. There’s one teleprompter hanging high up behind the audience, another is tucked down close to the stage. Some actors ignore the screens: Simpson mainly faces away from them, for instance. But Groff’s Isabella plants herself in a chair center-stage and . . . just . . . reads as fast as she can.

In an interview I once did with Collins about their 1997 play Cab Legs, the director referred to their decision to scramble a Tennessee Williams potboiler, Summer and Smoke: “Do the things you hate! It renews those contrarian impulses in an honest way.” With Measure, they’ve clearly found another play to hate. For an intermissionless two hours and ten minutes, we barely parse a word; the language is so quick, we only know when someone’s making a joke by the performer’s eye-roll and (that Shakespeare cliché) the grabbed crotch. The real laughs come during dumb-show: Simpson finds a cup of espresso in his pocket; April Matthis’s timid Mother Superior sends us a pregnant glance. These embroidered comic bits are gorgeous, but the production contains far too few. Instead, we spend most of our time with a largely intact Shakespeare play played at 1.5x speed. The enforced pace kills much of the performers’ timing, and when they’re gabbling their lines, you can often see their unease. So why not simply break the text? Why not take Shakespeare’s intentions and then run them through ERS’s customary disrespectful filter? Why do so much of the language if you feel the play is so patently bad?

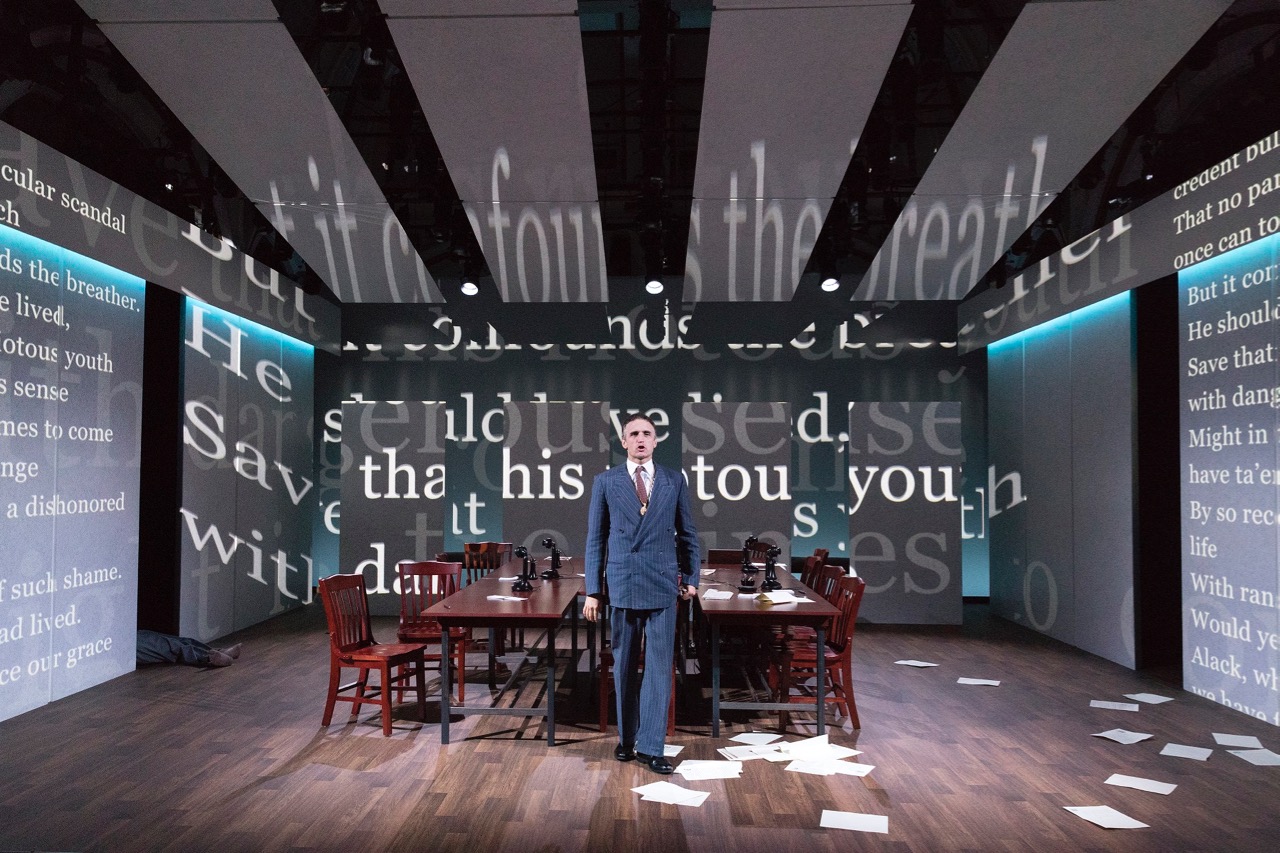

Scott Shepherd and Maggie Hoffman in Elevator Repair Service’s Measure for Measure. Photo: Richard Termine.

It’s an experiment that needs more ideas to be worth its duration—doing an already wobbly Shakespeare at a gallop teaches us only so much. There is, though, a hint that further work might yield results. In the confrontation between Isabella and her brother, the pace slows radically. Isabella and Claudio’s speech turns glacial; they caress every syllable. We suddenly have the time to think about the moment that virtue slips through our fingertips, always, for some reason, just as we’re grasping for it. The scene takes a slow-motion tumble from sweetness into horror, as Claudio haltingly, agonizingly, asks his sister to submit to a rape. Shakespeare might be on to something! The production is suddenly arresting! But then it accelerates back into senselessness.

Pete Simpson in Elevator Repair Service’s Measure for Measure. Photo: Richard Termine.

What exists right now at the Public seems about a third complete. They have the right Duke—Shepherd is a weasel prince, his eyes constantly flickering to the exits, slipping out the door of the theater just as the show comes to an end. They have a superb Angelo—the capering Simpson looks like the Looney Tunes version of a movie studio head, a terror out of our new national nightmare. But these two only appear together at the top and tail of the play, which become (apart from the sibling-confrontation scene) the only truly functioning bits in the show. That long, long middle stretch? It’s a difficult sit. Something more extreme needs to be done—these half-measures aren’t working.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, the Village Voice, TheatreForum, and diversalarums.com.