Christopher Richards

Christopher Richards

A candelabra with heads: formal innovation and unstable truth in Nicole Sealey’s first poetry collection.

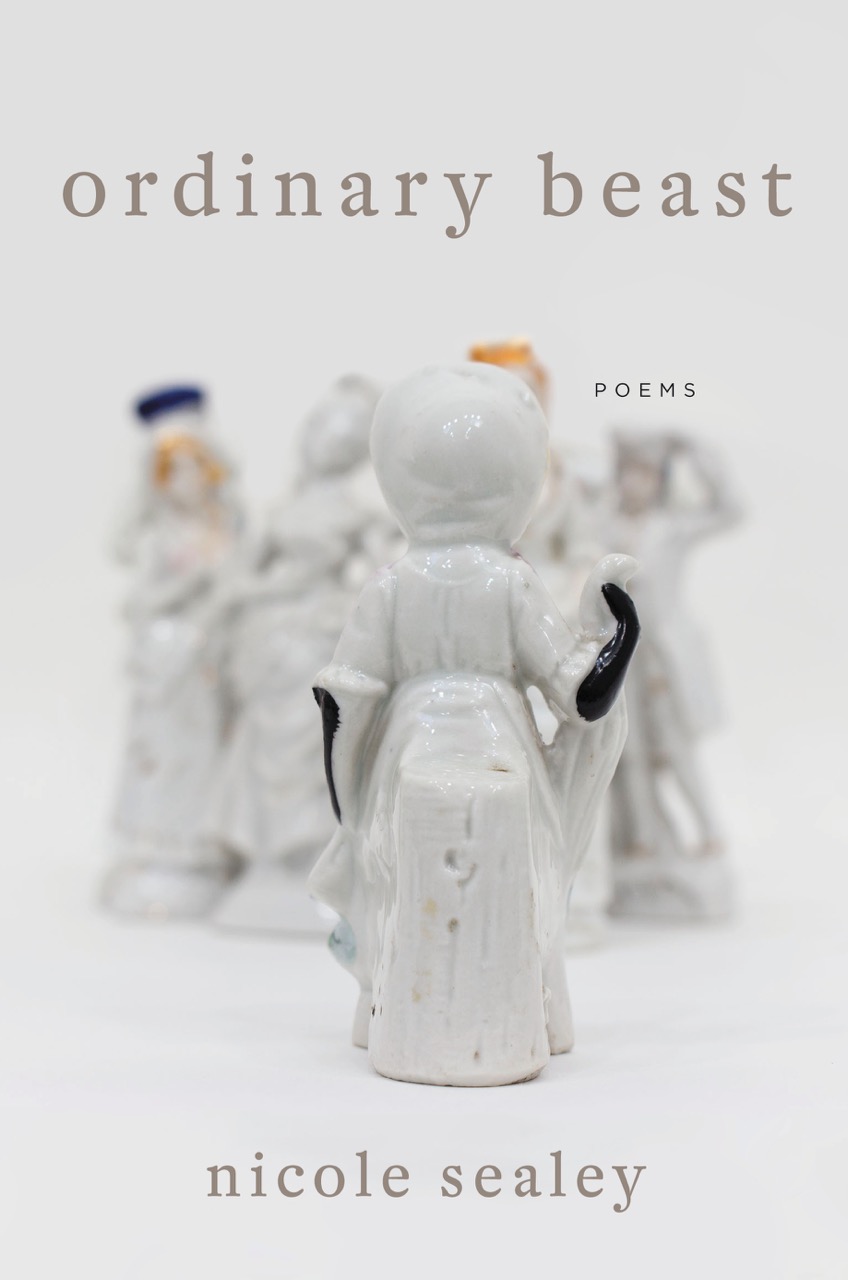

Ordinary Beast, by Nicole Sealey, Ecco, 64 pages, $24.99

• • •

In November 2016, a “bluish foreign body” was found by doctors under the eyelid of a British woman during routine surgery. The patient had an “uncomfortable and gritty” feeling in her eye, a complaint she chalked up to aging, although once the large glob was extracted it revealed itself to be twenty-seven disposable contact lenses, which she had failed to remove. This medical oddity was fodder for local newscasts, but it’s hard for me not to lift it up as a parable. How long we endure our self-made discomforts, how easily our vision can deceive us, how little we can be trusted with our own care.

Like us, the characters in Nicole Sealey’s debut poetry collection Ordinary Beast are burdened by eyes ill-equipped to read the world in front of them, minds distorted by the terrors of history, bodies all too aware of what she describes as our “brief animation.” Sealey, a US Virgin Islands-born and Florida-raised poet, has emerged as a vital figure in the contemporary poetry scene; she is also the executive director of Cave Canem Foundation, an organization dedicated to cultivating the voices of African American poets and as reliable an incubator of new talent as any MFA program. Despite being early in her career, Sealey bears the grace of a writer with full command over her gifts, a command that is thrillingly at odds with the out-of-joint universe of her poetry.

In one of Sealey’s most arresting poems, “candelabra with heads,” her speaker views a Thomas Hirschhorn sculpture and conjures the lurid scene of a lynching. In restless lines of self-examination, she thinks, “Had I not brought with me my mind / as it has been made, this thing, / . . . might be eight infants swaddled” or “eight fleshy fingers on one hand.” She understands that seeing takes part as much in the brain as it does in the eye—we adapt what we see into what our minds have come to expect, and here a sculpture of humanoid shapes mounted on a wooden scaffold with packing tape forms itself into a distinct scene of horror.

The poem is an obverse, a formal innovation invented by Sealey whereby the poem’s first half is repeated in reverse order in the second half of the poem (the fourteenth line repeats as the fifteenth line, the thirteenth line repeats as the sixteenth line, and so on). In “candelabra with heads” these reversals create new, frightening juxtapositions in thought, the structure of the poem escalating the obsessive dread. But rather than ending the poem with its first line—as the form would lead the reader to anticipate—Sealey subverts our expectation and concludes with a new line that is the poem’s thesis: “Who can see this and not see lynchings?” Formal structures—including sonnets, sestinas, a cento, an erasure, standard rhyme schemes—are employed throughout Ordinary Beast, and Sealey’s playful use of them is organic and instinctive. While her adventures in style and form aren’t uniformly satisfying, they refreshingly demonstrate a provocative point of view rather than mere banal displays of skill. In Sealey’s poems, we are bound to history, particularly the dreadful legacy of racism, and her formalism can read as a subtle acknowledgment of the preexisting world we are born into and have to make our way against.

Ordinary Beast opens with “medical history,” a sonnet in which the speaker details a litany of ailments suffered by her and her family. The suffering in the bodies of her elders appears to be destiny, history is in their flesh. The turn in the sonnet provides us, and the speaker, with no comfort. After the causes of death of two relatives are named (aneurysm, heart attack), we learn that an uncle has eluded the family’s history of disease by being hit by a car. The poem resolves itself in a brutal fiction: “the stars in the sky are already dead.” Most of the stars we see are not in fact dead. But can we blame the speaker for thinking this amid the experiences of her kin?

One of Sealey’s more beguiling tricks is how she rearranges perspective. “imagine sisyphus happy” invites us to see suffering as a natural craving, and the speaker begs to be left alone to indulge in it.

Deer sniff lifeless fawns before leaving,

elephants encircle the skulls and tusks

of their dead—none wanting to leave

the bones behind, none knowing

their leave will lessen the loss.

The speaker implores “Allow me this / luxury. Give me tonight to cut / and salt the open.”

With her quicksilver language and sleights of hand, what exactly is Nicole Sealey up to? Take the end of her poem “in igboland,” which centers around townspeople building a “mansion / of dirt” for a god who has just unleashed “plagues of red locusts.” Imagining this sacrifice set ablaze, she writes:

Every thing aspires to one

degradation or another. I want

to learn how make something

holy, then walk away.

The temptation is to read “in igboland” as an ars poetica and there’s certainly some sincerity to the lines. But her slyness makes it difficult to accept her words at face value. Throughout the collection identity is fluid; expressions of self are refracted through the voices of others (particularly in “legendary,” a sequence of poems about the drag queens and trans women from the documentary Paris Is Burning). Truth, where it can be found, is unstable. Perhaps the most vulnerable and unguarded poem in the collection is “cento for the night i said, ‘i love you,’ ” a raw and piercing work whose intimacy is belied by its form: a cento is a magpie poem drawn completely from quotation.

When poet Lucille Clifton was asked about why she wrote children’s literature, she responded, “Children—and humans, everybody—all need both windows and mirrors in their lives: mirrors through which they can see themselves and windows through which they can see the world.” In an interview with the website Brooklyn Poets, Sealey quoted this pearl from Clifton while describing the merits of finding her “reflection” in her neighbors in Crown Heights, but it could just as easily be a description of her achievement in Ordinary Beast: creating mirrors and windows. The mirrors may be convex or cracked, the windows curtained over or stained; seeing is never simple in Sealey’s world, a place where “even the gods misuse,” “misread,” and “misquote.” But still she grants us glimpses of exquisite clarity—about blackness in America, about love in the face of mortality—and more than a little beauty for our bleary eyes.

Christopher Richards is a poet and editor from Minnesota. He has contributed to The New Yorker’s Page-Turner, The Nation, The Millions, Guernica, and After Dark.